Candace Robb

The Margaret Kerr Series:

Book Two

THE FIRE IN THE FLINT

2003

In loving memory of my mother,

Genevieve Wojtaszek Chestochowski

(19 March 1920 16 July 2003)

whose courageous battle with cancer

showed me what stuff women are made of

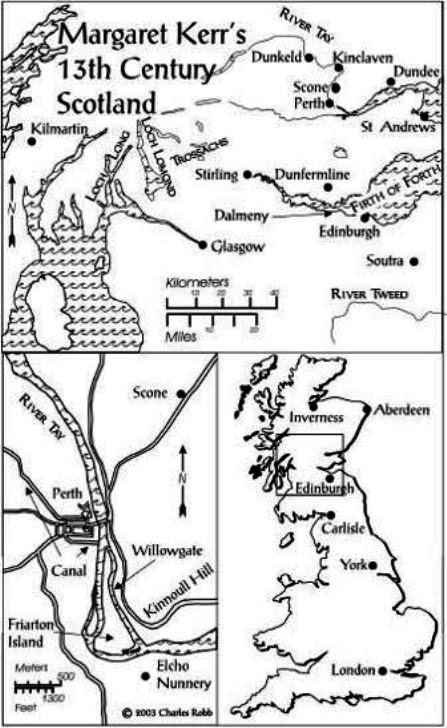

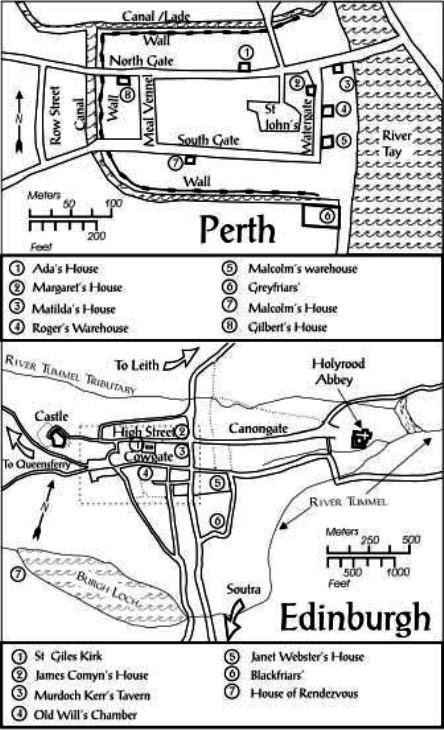

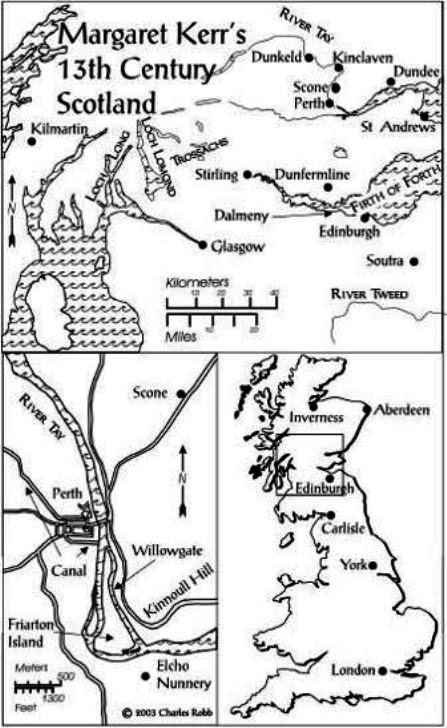

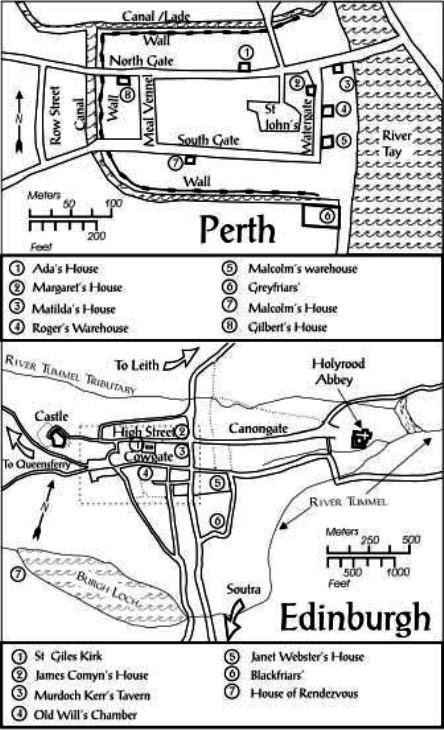

My thanks to Elizabeth Ewan, Kimm Perkins, Nicholas Mayhew, and David Bowler, Derek Hall and Catherine Smith of the Scottish Urban Archaeological Trust, generous scholars who have fielded my questions and kept me honest about medieval Scotland and coinage; Evan Marshall, Joyce Gibb, Elizabeth Ewan, and Kirsty Fowkes who read the manuscript and made thoughtful suggestions; Jan and Chris Wolfe of the Willowburn Hotel on Seil Island who loaned me a book about Argyll, pointing out the magical glen of Kilmartin; and Charlie Robb who photographed locations, sat in on meetings, crafted the maps, and simplified travel and home with tender loving care.

With the death of the Maid of Norway, who was the last member in the direct line of kings of Scotland from Malcolm Canmore, two major claimants of the throne arose John Balliol and Robert Bruce; eventually ten additional claimants stepped forward. In an effort to prevent civil war, the Scots asked King Edward I of England to act as judge. In hindsight, they were tragically unwise to trust Edward, who had already proved his ruthlessness in Wales. Edward chose John Balliol as king, and then proceeded to make a puppet of him.

Robert Bruce, known as the Competitor to distinguish him from his son Robert and his grandson Robert, still seething under the lost opportunity, handed over his earldom to his son, who was more an Englishman at heart than a Scotsman. He in turn handed over the earldom to his son, who would eventually become King Robert I. Through the 1290s this younger Bruce, Earl of Carrick, vacillated between supporting and opposing Edward. When he at last resolved to stand against Edward, he was not doing so in support of John Balliol, but was pursuing his own interests.

As for William Wallace, he was in 1297 and thereafter fighting for the return of John Balliol to the throne. He was never a supporter of Robert Bruce.

The fire i the flint

Shows not till it be struck

Timon of Athens, Act I, l. 22

oftentimes, to win us to our harm,

The instruments of darkness tell us truths,

Win us with honest trifles, to betrays

In deepest consequence.

Macbeth, Act I, scene iii, ll. 123-126.

Though it was close to midnight, twilight glimmered on the water meadow between Elcho Nunnery and the River Tay. Night creatures croaked and called in the background, and ahead the waters of the Tay and the Willowgate roiled and splashed as they joined at the bend beneath Friarton Island. Christianas bare feet cracked the brittle crust of the soil dried by the summer drought. With her next step, her right foot sank to the ankle bone in saturated ground. With a shiver of loathing, she freed herself. For the twenty-three years of her marriage she had lived just upstream in Perth, and in all that time she had remained unreconciled with this marshy land. She had grown up amidst mountains, lochs, and the high banks of the Tay upriver. She missed the sharp, fresh air and the land always solid beneath her feet. Here the fields along the river were unpredictable, sometimes more water than land, changing with the weather, as uncanny as her mind.

Terror had awakened her. She had fled her chamber in the nunnery guest house, sensing an intruder, a feeling so strong she had thought she heard his breath, breath which she still felt at the nape of her neck. Fear had squeezed her heart and compelled her to run. Now on the marshy ground she slowed down, though still hardly daring to breathe. She glanced back over her shoulder in dread, but although the July night was light enough that she might have seen any movement, she saw no one. Gradually, as the chill of her wet feet drove away any remnant of sleep, she remembered that her handmaid had not stirred on her cot at the foot of the bed. The intruder had not been a fleshly presence then, but a vision.

Christiana struggled to reconstruct the confusing face. It had seemed that as the man turned his features shifted, changing so quickly it was as if his face were drawn in oil and his movement stirred the lines. It was too fluid to know whether any part of it was familiar. Or perhaps hed worn many faces overlaying one another. She could not recall precisely where in the dim room she had seen him as she woke and rose breathless.

On the river bank she stopped and tried to calm herself by listening to the water and imagining it washing away the residue of fear. But her attention was drawn across the river to the cliff overhanging the opposite bank. In the midnight sun someone standing at the edge would be able to see her. She felt too vulnerable for calm.

Her mind eased a little when she remembered that the sisters would soon awaken to sing the night office; then she might seek sanctuary in the kirk. Turning her back on the disturbing cliff, she was puzzled to see lights multiplying in the priory buildings, flickering as the candle- and lamp-carriers moved in and out of the window openings and doorways. They were moving across the yard, not in the direction of the kirk but the guest house whence she had fled.

Perhaps they had been awakened by the intruder she had foreseen. She must go back, she might be able to help why else would God have warned her? As she walked towards the nunnery she heard womens cries and the authoritative barks of the prioress. The voices drowned out the rivers quiet song. She called out to the lay servant guarding the nunnery gate, and two sisters ran out to her, one with a lantern swinging so wildly beside her that Christiana had to shield her eyes against the dizzying dance of light.

Dame Christiana! We feared you had been taken!

Are you injured? the other asked.

Your handmaid cannot be consoled, fearful youre dead, said the first.

Christiana could not bear the dancing light. Steady the lantern, I beg you.

The sister complied, and Christiana was now able to focus on the two who seemed to speak as one. As you see, I am neither dead nor injured, thanks be to God. Is the intruder still in the grounds?

You knew about them?

Them, Christiana said. So there had been more than one. She had not the energy to explain. Forgive me, but I must see my chamber. She pushed through milling servants and sisters and into the guest-house garden, which looked trampled in the moonlight. Two voices came from the opened door, one reassuring, one pitched high with emotion. Christiana stepped over the threshold.

Dame Katrina, the elderly hosteleress, sat holding a servants hands as she said, You are not to blame.

I should have heard them on the steps! the servant cried.

Christiana interrupted. Did they enter the hall? she asked.

Both women started. The servant shook her head.

Christiana hurried out and up the steps to her chamber. She found her handmaid Marion weeping in the protective arms of Prioress Agnes.

Marion, calm yourself, Christiana said with a sharpness that she had not intended. She inclined her head. Prioress Agnes.

Marion glanced up, her eyes widening in surprise, and cried, You are safe! Praise God. She rubbed her eyes as if to clear her vision and make certain shed seen aright.