Candace Robb

The Margaret Kerr Series:

Book Three

A CRUEL COURTSHIP

2005

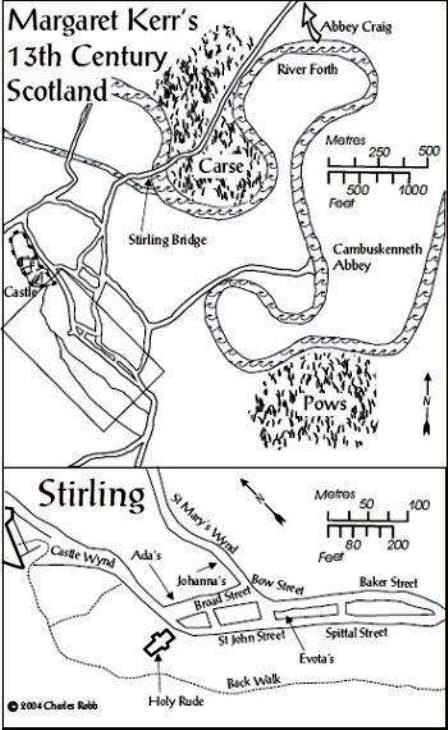

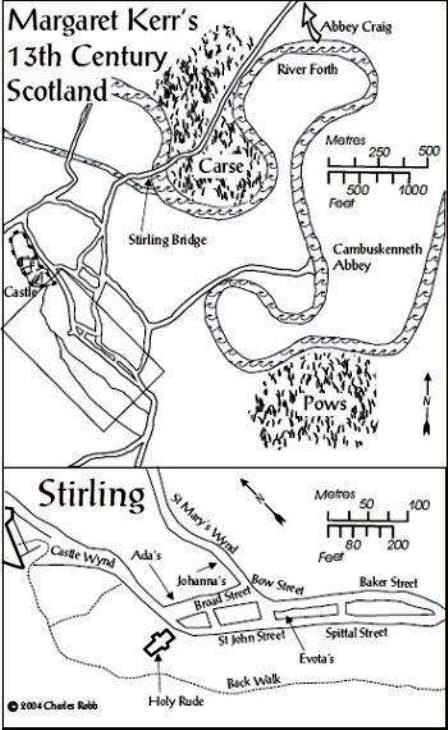

In Memory of Hilde Bial Neurath

I wish to thank Elizabeth Ewan for sharing with me her research in Scottish women and Scottish history, as well as for reading and critiquing a draft of this book; Kimm Perkins for her research in medieval Scottish nunneries; David Bowler of the Scottish Urban Archaeological Trust for pointing me towards detailed maps of Stirling; Kate Elton, Joyce Gibb, Georgina Hawtrey-Woore and Evan Marshall for careful readings and critiques of the manuscript; and Charlie Robb for photos, maps, and tender loving care on our travels and at home.

Last but certainly not least, I want to thank Peter Neurath for inspiring some aspects of Peter Fitzsimon his physique, his good looks, and the idea that he posed to me that a great warrior might have fear as the sole motivation for honing his fighting skills. Peter donated a generous sum of money to the Washington State Alzheimers Association to appear in one of my books and what do I do, I make him an unsavoury character! But hed given me carte blanche with good humour. Peters generous gift to this non-profit organisation, which provides much-needed support for those caring for Alzheimer victims, was in memory of his mother, Hilde Bial Neurath, and I in turn dedicate this book to her. In her willingness to open her house to Margaret at a dangerous time, Ada is a kindred spirit to Hilde, whom Peter described as loving to match people with the perfect house, being a terrific hostess, and enjoying good conversation.

barded: caparisoned, protected with armour

carse: marsh

cockered: pampered

cruisie: an oil lamp with a rush wick

gey: very

Holy Rude: rude is dialect for rood, or cross; the name of the kirk (not to be confused with Holyrood Abbey in Canongate) is still spelled this way

pows: marshy area south of the Forth River, named for all the streams, or pols (becoming pows), that drain it

spital: hospital

Was ever woman in this humour wooed?

Was ever woman in this humour won?

Ill have her, but I will not keep her long.

Richard III, Act I, scene ii, ll. 228-230

oftentimes, to win us to our harm,

The instruments of darkness tell us truths,

Win us with honest trifles, to betrays

In deepest consequence.

Macbeth, Act I, scene iii, ll. 123-126

For this execution the gallows in the bailey of Stirling Castle would not suffice; a special one was set up in the market square so that the townsfolk would find it difficult to avoid. Huchon Allan was a traitor. Hed been caught about to ford the River Forth with more weapons than one man could reasonably use William Wallace and Andrew Murray were gathering their Scottish rabble on the far side of the river and the English accused Huchon of intending to take the weapons to them. His hanging would serve as a warning to the Scots of Stirling that King Edward of England would not turn the other cheek.

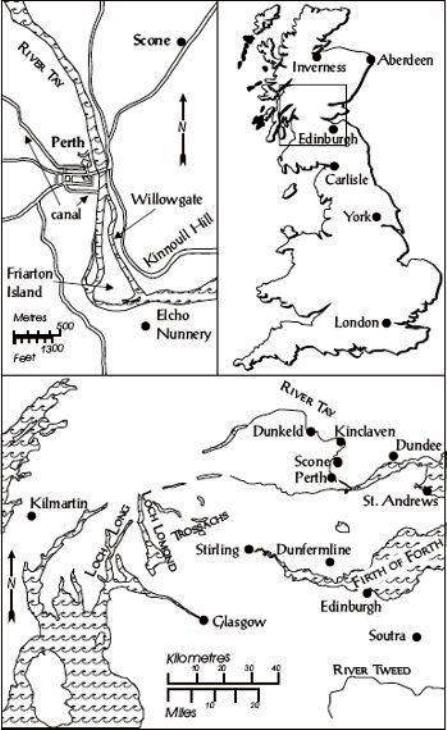

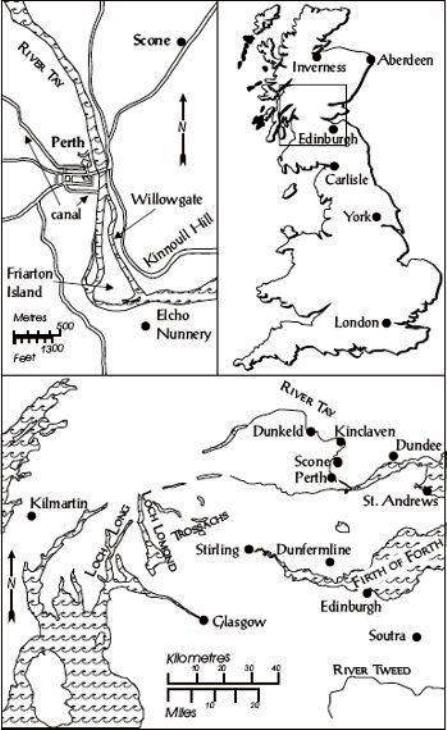

Johanna had never known such fear as she suffered now, nor such a debilitating guilt. She did not doubt the righteousness of her cause, to return King John Balliol to the throne that King Edward of England had stolen, but the danger for her and for her lover, Rob, had never been so real, so clear. She knew from Rob, a soldier at the castle and her unwitting informant, that the English were furious about the raiding of Inverness and Dundee by Murray and Wallace, and that they were expecting reinforcements soon. They were abandoning their earlier efforts to keep peace in the town, convinced that their generosity had simply bred rebellion.

Johanna had much to tell Archie, the lad who carried the information she coaxed from Rob down to someone in the valley who passed it on to Murrays and Wallaces men. But shed not seen the lad in days. When shed first heard that a traitor had been caught shed feared for Archie, or for Rob, and had been giddy with relief that it was Huchon. But her relief had not lasted, for she knew and liked Huchon and his family, and his capture brought home to her the mortal danger in which she was placing Rob. She worried even more about Archie and what kept him away of late. Shed found it difficult to trust him; in fact shed urged Father Piers to find someone else to carry the messages. The priest had argued that there was no one else foolhardy enough to take the risk, and they needed someone small and known to be a forager, a lad folks were accustomed to seeing everywhere.

For two days Johanna had been unable to keep anything down, so real had the danger of her activity become to her. Yet on the day of the hanging she could not stay away from the square. She arrived just in time to see Huchons parents, Ranald and Lilias, led from their house by soldiers. The expressions on the Allanss faces broke Johannas heart. Only when they were in their designated position at the head of the small group facing the galley was their son led from the kirk at the top of the street and down towards them, paced by a mournful drumming.

His betrothed has been sent away to kin in the highlands, said the woman beside Johanna. She should have been here.

Hush, Mary, shes too young to witness such a thing, said another woman.

Johanna had not known Huchon was betrothed, but she did not ask to whom, trusting no one now. She said a prayer for the young woman, pitying her for such a horrible end to her betrothal.

Peter, a young, handsome, well-spoken English soldier, read the accusations against Huchon. His manner chilled Johanna, for he read Huchons death sentence with indifference, as if it meant nothing to those watching.

Suddenly several things happened at once. As the soldiers tied Huchons hands behind his back and covered his eyes, his mother lunged towards Peter and grabbed his hand screaming, What right have you to wear that? Thief!

Her husband grabbed Lilias at almost the moment that Huchon dropped, his body doing a ghastly jig, his face darkening.

Johanna fell to her knees, hiding her own face in her hands. Dear God, may he rest in peace, she whispered over and over to shut out the horrible screams of Lilias Allan.

Perth, end of August, 1297

As the summer wore on the presence of King Edward of Englands army in Perth began to fray the tempers of the townsfolk. Women increasingly complained of the rude behaviour of the soldiers, and theft was rampant, the thieves aware of the backlog of more serious crimes to be presented at gaol delivery sessions than their small felonies. The walls that the army had reinforced and extended now surrounded the town on three sides, cutting off the merchants access to their warehouses from the ships in the canal. The English might have compensated for some of the inconvenience by allowing general access along the riverfront on the east it would have quieted tempers and cost them little in security. Instead they restricted access from the River Tay, allowing only one ship per day to offload. Now ships might idly sit at anchor in the river for days, impeding traffic and slowing trade to almost a standstill. Even though the fighting in Dundee at the mouth of the Tay made shipmen hesitant to sail upriver, some still did, and to the townsfolk the restrictions were symbolic of the potential loss of freedom if Edward Longshanks was not defeated.