Annette Insdorf: I gather that Smoke began with a Christmas story you wrote for The New York Times.

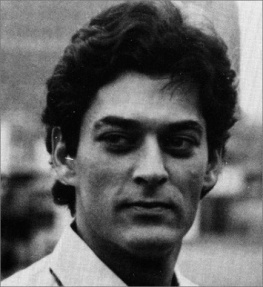

Paul Auster: Yes, it all started with that little story. Mike Levitas, the editor of the Op-Ed page, called me out of the blue one morning in November of 1990. I didnt know him, but he had apparently read some of my books. In his friendly, matter-of-fact way he told me that hed been toying with the idea of commissioning a work of fiction for the Op-Ed page on Christmas Day. What did I think? Would I be willing to write it? It was an interesting proposal, I thoughtputting a piece of make-believe in a newspaper, the paper of record, no less. A rather subversive notion when you get right down to it. But the fact was that I had never written a short story, and I wasnt sure Id be able to come up with an idea. Give me a few days, I said. If I think of something, Ill let you know. So a few days went by, and just when I was about to give up, I opened a tin of my beloved Schimmelpennincksthe little cigars I like to smokeand started thinking about the man who sells them to me in Brooklyn. That led to some thoughts about the kinds of encounters you have in New York with people you see every day but dont really know. And little by little, the story began to take shape inside me. It literally came out of that tin of cigars.

AI: Its not what I would call your typical Christmas story.

PA: I hope not. Everything gets turned upside down in Auggie Wren. Whats stealing? Whats giving? Whats lying? Whats tellingthe truth? All these questions are reshuffled in rather odd and unorthodox ways.

AI: When did Wayne Wang enter the picture?

PA: Wayne called me from San Francisco a few weeks after the story was published.

AI: Did you know him?

PA: No. But I knew of him and had seen one of his films, Dim Sum, which I had greatly admired. It turned out that hed read the story in the Times and felt it would make a good premise for a movie. I was flattered by his interest, but at that point I didnt want to write the script myself. I was hard at work on a novel [ Leviathan ] and couldnt think about anything else. But if Wayne wanted to use the story to make a movie, that was fine by me. He was a good filmmaker, and I knew that something good would come of it.

AI: How was it, then, that you wound up writing the screenplay?

PA: Wayne came to New York that spring. It was May, I think, and the first afternoon we spent together we just walked around Brooklyn. It was a beautiful day, I remember, and I showed him the different spots around town where I had imagined the story taking place. We got along very well. Wayne is a terrific person, a man of great sensitivity, generosity, and humor, and unlike most artists, he doesnt make art to gratify his ego. He has a genuine calling, which means that he never feels obligated to defend himself or beat his own drum. After that first day in Brooklyn, it became clear to both of us that we were going to become friends.

AI: Were any ideas for the film discussed that day?

PA: Rashid, the central figure of the story, was born during that preliminary talk. And also the conviction that the movie would be about Brooklyn . Wayne went back to San Francisco and startedworking with a screenwriter friend of his on a treatment. He sent it to me in August, a story outline of ten or twelve pages. I was with my family in Vermont just then, and I remember feeling that the outline was good, but not good enough. I gave it to my wife Siri to read, and that night we lay awake in bed talking through another story, a different approach altogether. I called Wayne the next day, and he agreed that this new story was better than the one hed sent me. As a small favor to him, he asked me if I wouldnt mind writing up the treatment of this new story. I figured I owed him that much, and so I did it.

AI: And suddenly, so to speak, your foot was in the door.

PA: Its funny how these things work, isnt it? A few weeks later, Wayne went to Japan on other business. He met with Satoru Iseki of NDF [Nippon Film Development] about his project, and just in passing, in a casual sort of way, he mentioned the treatment I had written. Mr. Iseki was very interested. Hed like to produce our film, he said, but only if Auster writes the script. My books are published in Japan, and it seemed that he knew who I was. But he would need an American partner, he said, someone to split the costs and oversee production. When Wayne called me from Tokyo to report what had happened, I laughed. The chances of Mr. Iseki ever finding an American partner seemed so slim, so utterly beyond the realm of possibility, that I said yes, Ill do the screenplay if theres money to make the film. And then I immediately went back to writing my novel.

AI: But they did find a partner, didnt they?

PA: Sort of. Tom Luddy, a good friend of Waynes in San Francisco, wanted to do it at Zoetrope. When Wayne told me the news, I was stunned, absolutely caught off guard. But I couldnt back out. Morally speaking, I was committed to writing the script. I had given my word, and so once I finished Leviathan [at the end of 91], I started writing Smoke . A few months later, the deal between NDF and Zoetrope fell apart. But I was too far into it by then to wantto stop. I had already written a first draft, and once you start something, its only natural to want to see it through to the end.

AI: Had you ever written a screenplay before?

PA: Not really. When I was very young, nineteen or twenty years old, I wrote a couple of scripts for silent movies. They were very long and very detailed, seventy or eighty pages of elaborate and meticulous movements, every gesture spelled out in words. Weird, deadpan slapstick. Buster Keaton revisited. Those scripts are lost now. I wish to hell I knew where they were. Id love to see what they looked like.

AI: Did you do any sort of special preparation? Did you read scripts? Did you start watching movies with a different eye toward construction?

PA: I looked at some scripts, just to make sure of the format. How to number the scenes, moving from interiors to exteriors, that kind of thing. But no real preparationexcept a lifetime of watching movies. Ive always been drawn to them, ever since I was a boy. Its the rare person in this world who isnt, I suppose. But at the same time, I also have certain problems with them. Not just with this or that particular movie, but with movies in general, the medium itself.

AI: In what way?

PA: The two-dimensionality first of all. People think of movies as real, but theyre not. Theyre flat pictures projected against a wall, a simulacrum of reality, not the real thing. And then theres the question of the images. We tend to watch them passively, and in the end they wash right through us. Were captivated and intrigued and delighted for two hours, and then we walk out of the theater and can barely remember what weve seen. Novels are totally different. To read a book, you have to be actively involved in what the words are saying. You have to work, you have to use your imagination. And once your imagination has been fully awakened,you enter into the world of the book as if it were your own life. You smell things, you touch things, you have complex thoughts and insights, you find yourself in a three-dimensional world.