Bernard Knight

CROWNER ROYAL

A Crowner John Mystery

2009

Professor Bernard Knight, CBE, became a Home Office pathologist in 1965 and was appointed Professor of Forensic Pathology, University of Wales College of Medicine, in 1980. During his forty-year career with the Home Office, he performed over 25,000 autopsies and was involved in many high profile cases.

Bernard Knight is the author of twenty-three novels, a biography and numerous popular and academic non-fiction books. Crowner Royal is the thirteenth novel in the Crowner John Series.

You are welcome to visit his website at

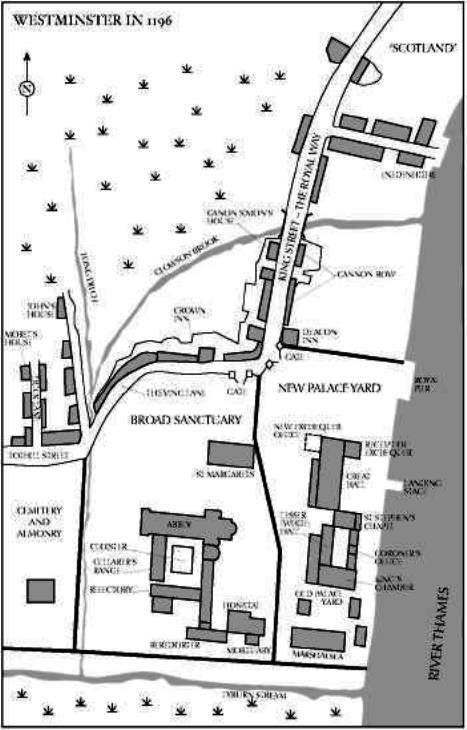

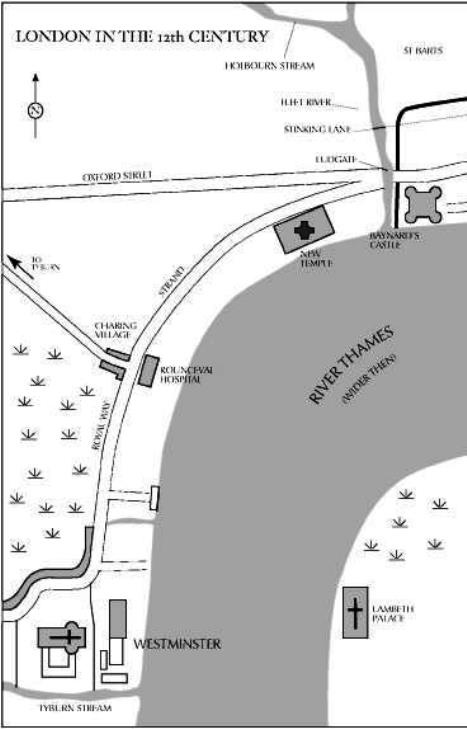

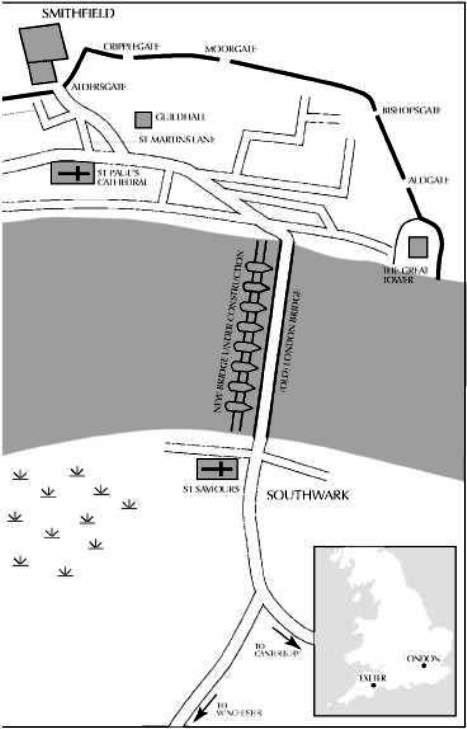

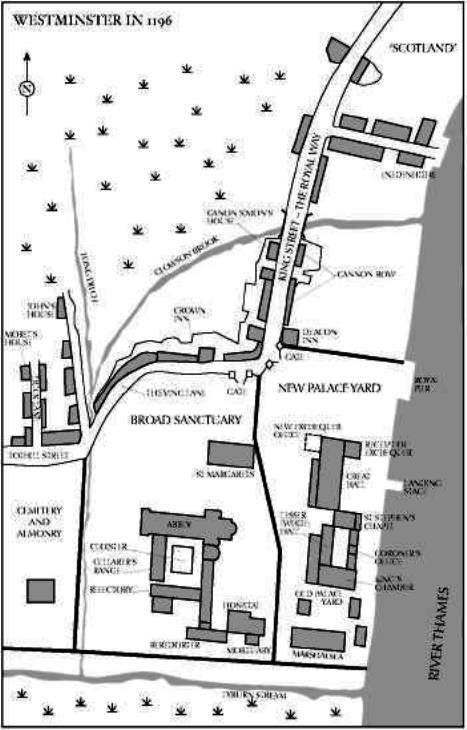

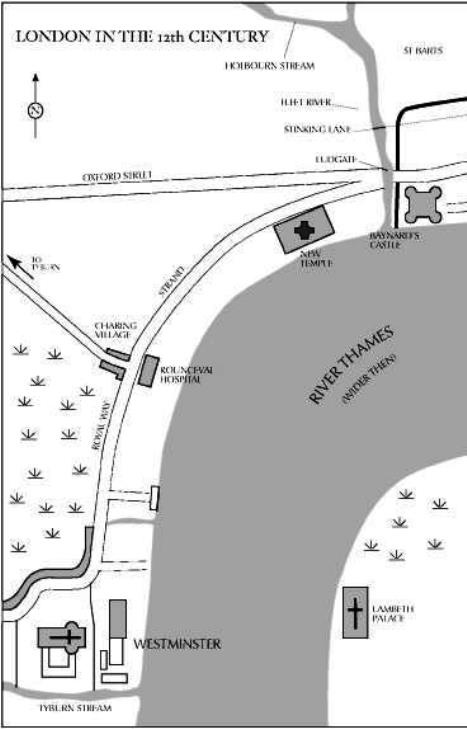

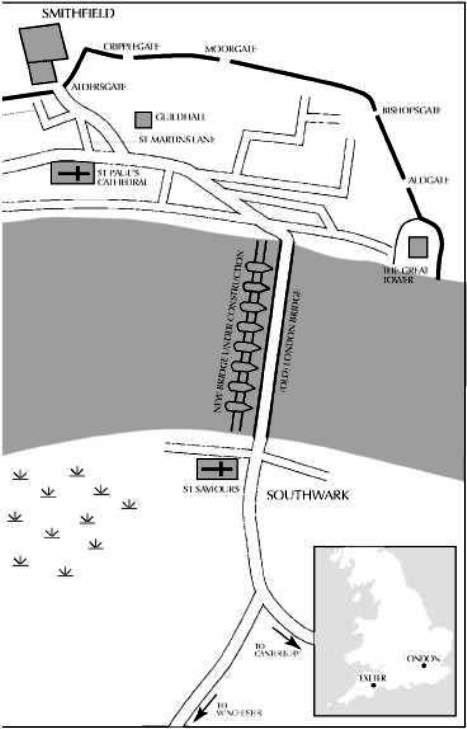

In the twelfth century, the vital Exchequer of the Royal Council (the Curia Regis), which governed England, gradually moved from the old Saxon capital of Winchester to London. It was housed in the Palace of Westminster, which was also the main residence of the king though when in England, the kings (especially Henry II and John) spent much of their time away from Westminster, progressing around the countryside with their huge court retinues.

William the Conqueror had first resided in the Great Tower (later known as the Tower of London), which he built to dominate the city, but he later moved into Edward the Confessors old palace at Westminster, depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry though like most monarchs until John, he spent little time in England. His son William Rufus began rebuilding the palace and his huge Westminster Hall, dating from 10979, was the largest in Europe and is still in use today. For centuries, the rest of the palace grew piecemeal around it, several times being devastated by fire, which eventually caused Henry VIII to abandon it as a royal residence and move to the nearby Palace of Lesser Hall. The present huge edifice which houses Parliament, was the result of almost total rebuilding after the fire of 1834, Westminster Hall being virtually the sole survivor of the Norman structure, together with the crypt of St Stephens Chapel, which was the first home of the House of Commons.

The palace was only yards from the Confessors great abbey, between it and the river. In those days, before the Thames was confined within embankments, it was much wider and shallower, being fordable at low tide just above the palace at Horseferry. The whole area was marshy, often flooded, so Westminster was built on a gravel bank, known as Thorney Island because it was covered in brambles. A number of streams drained the marshes, such as the Tyburn, which formed the southern boundary of the Westminster settlement.

A small town grew up around the abbey and palace, which was less than two miles from the walled city of London. From Westminster, a country road passed through the village of Charing and along the Strand, past the New Temple of the Knights Templar to Ludgate, just across the Holbourn stream, later called the Fleet.

The exact topography of Westminster in the twelfth century is not precisely known, but archaeologists are still discovering traces, such as those found between 1991 and 1998 during excavations for the extension of the Jubilee Underground line. In addition to the many clerks, court officials and tradesmen who lived there, some of the Ministers of State had town houses, though others lived in the palace itself.

What is clear is the economic and political divide that existed between Westminster and the city, as it does to this day. The former was an administrative and monastic centre, whilst the fiercely independent city was the commercial hub of England, with the competition and jealousies between them never far below the surface. In the Middle Ages, the city was sometimes for, and sometimes against, the reigning monarch, as when they supported King Stephen against Empress Matilda or the barons against King John.

Relations with government were not always easy: the city demanded the right to appoint its own mayor in 1193, and in 1194 they did not accept the imposition of the coroner system, their two sheriffs carrying out these functions in the city and the county of Middlesex. At a distance of over 800 years, it is unclear how the jurisdiction of the Coroner of the Verge, around which this Crowner John story revolves, clashed with these other entrenched interests, but it seems likely that he did not have an easy time.

The Coroner of the Verge dealt with all cases within a twelve-mile radius of the court, wherever that might be on its frequent procession around England. Later, this office became known as The Coroner to the Royal Household, which in very recent times came into the public eye in relation to the controversial inquest into the death of Princess Diana.

One of the problems of writing a long series of historical novels, of which this is the thirteenth, is that regular readers will have become familiar with the background and the main characters and may become impatient with repeated explanations in each book. On the other hand, new readers need to be brought up to speed to appreciate some of the historical aspects, so a Glossary is offered with an explanation of the medieval terms used, especially relating to the functions of the coroner, one of the oldest legal offices in England.

Any attempt to use olde worlde dialogue in a novel of this early period would be as inaccurate as it would be futile, for in the late twelfth century, most people would have spoken Early Middle English, quite incomprehensible to us today. The ruling classes would have used Norman-French, while the language of the Church and virtually all writing was Latin. Few people could read and write, literacy being virtually confined to the few people who were clerics in Holy Orders. Only a minority of these clerics were ordained (bishops, priests and deacons), most being in minor orders, unable to celebrate mass, take confessions and give absolutions. These were clerks, lectors, sub-deacons and doorkeepers and there were even more lay brothers who performed the menial work of religious institutions.

All the names of characters in the book are authentic, who are either actual historical persons or taken from the court rolls of the period.

The only money in circulation would have been the silver penny, apart from a few foreign gold coins known as bezants. The average wage of a working man was about two pence per day and coins were cut into halves and quarters for small purchases. A pound was 240 pence (100p) and a mark 160 pence (66p), but these were nominal accounting terms, not actual currency.

ABJURING THE REALM

A criminal or fugitive gaining sanctuary in a church, had forty days grace in which to confess to the coroner and then abjure the realm, that is, leave England, never to return. France was the usual destination, but Wales and Scotland could also be used.

He had to dress in a sackcloth and carry a crude wooden cross to a port nominated by the coroner. He had to take the first ship to leave for abroad and if none was available, he had to wade out up to his knees in every tide to show his willingness to leave. Many abjurers absconded