To the memory of

Ehud Netzer,

1936 2010

A rchaeologist extraordina i r e

and friend sorely missed

My thanks are due to four archaeologists and maritime historians who have been extraordinarily generous with their help in tracing the movements of a long-dead English king and gave permission for my use of their copyrighted material published in academic papers and books: Professor John H. Pryor of the Centre for Medieval Studies at the University of Sydney, NSW; and Professor Emeritus Sarah Arenson and Dr Ruthy Gertwagen of the University of Haifa. The late Professor Emeritus Ehud Netzer of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Dvorah Netzer not only shared much knowledge with me, but also extended warm welcome and hospitality on my visits to Israel.

Professor Friedrich Heer of the University of Vienna used Jacob Burckhardts light to illuminate some dark periods of history for me; my Gascon friends Nathalie and Eric Roulet opened my eyes and ears to Occitan as a living language; Eric Chaplain of Princi Neguer publishing house in Pau lent precious source material in that and other languages; fellow-author and horsewoman Ann Hyland gave valuable equestrian advice; Jennifer Weller, a wonderful artist, took time out to draw maps and seals; Tuvia Amit helped with details of Arsuf/Apollonia; La Socit des Amis du Vieux Chinon authorised me to photograph the unique fresco in the Chapelle Ste-Radegonde; my former comrades-in-arms John Anderson and Colin Priston researched the massacre at York and Hodierna Nutrix, the mystery woman in King Richards life; the staffs of La Bibliothque Nationale de France and its online resource Gallica , of the British Library and of the Bibliothque Municipale de Bordeaux made available much source material; that doyen of literary translators, Miguel Castro Mata threw new light on the crusader fleets stopovers in Portugal; and my partner Atarah Ben-Tovim was an enthusiastic companion following Richard Is travels on both sides of the Channel, in Sicily and the Levant.

Lastly, although chronologically first, I acknowledge my debt to two great teachers, Latinist William McCulloch and George Trotman, an inspiring teacher of French and Spanish, both sometime of Simon Langton School for Boys, Canterbury. Together, they unleashed my passion for linguistics, without which this book, drawn from sources in eight medieval and modern languages, would not have been written.

At The History Press, my thanks go to commissioning editor Mark Beynon, project editor Rebecca Newton, proofreader Emma Wiggin, designer Jemma Cox and cover designer Martin Latham.

With so much expert support, it goes without saying that any errors are mine.

Contents

In the twenty-first century, despite all the tools of enquiry at their disposal, western journalists creating history as it happens overwhelmingly endorse hand-outs from the Pentagon and Downing Street, so that British and American wars are presented as democratic actions undertaken for humanitarian reasons and fought with due respect for human life and protection of non-combatants, even when the government hand-outs are known by many of those journalists to be patently false, and incontrovertible evidence of war crimes exists. Anyone believing differently need only watch John Pilgers 2010 documentary The War You Dont See , which includes shattering admissions of this practice by well-known journalists and elected politicians, government officials and service personnel admitting their morally and legally unacceptable actions in the Iraq War of 200311.

History as a record of the past can also be misleading. Living two and a half millennia ago, Herodotus was later dubbed by Cicero the father of history because he was the first person to attempt recording the past methodically. His investigation into the origins of the GrecoPersian wars gave us the word we use today: istoria , meaning learning by enquiry. That is the business of historians, of the present or the past.

The first Roman historian to write in Latin was Cato the Elder in the second century BCE . To him, the point of recording the past was to prove the superiority of the Roman race and way of life, and his successors continued to present the Romans always as the good guys and all Romes wars as just. So, almost from the beginning, history was perverted from Herodotus open-minded spirit of enquiry by what we today call spin, varying from the ethnically biased Roman accounts to the nineteenth-century view of German historian Leopold von Ranke that history should demonstrate a divine plan, with the hand of God manifest in the deeds of men, even when this meant snipping the pieces of times jigsaw to fit. Rankes contemporary, the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, disagreed, holding that all events should be recorded, whether or not they seem to fit any divine or other plan. However, the teaching of history in Britains universities followed the Protestant school of Ranke, thanks largely to the great classical scholar Bishop William Stubbs of Oxford. This Christian spin on the teaching and study of history at British universities and therefore British schools lasted into the second half of the twentieth century.

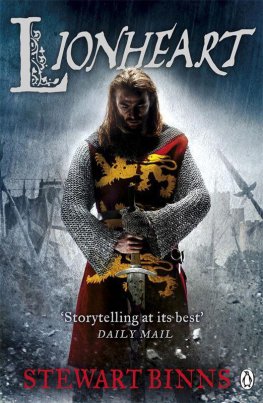

To Stubbs, King Richard I of England should have been seen as a heroic figure because he led the Third Crusade with the intention of reconquering Jerusalem from the Saracen. In fact, Stubbs opinion was that Richard was a bad ruler; his energy, or rather his restlessness, his love of war and his genius for it, effectively disqualified him from being a peaceful one; his utter want of political common sense from being a prudent one. Stubbs considered opinion was that Richard was a man of blood, whose crimes were those of one whom long use of warfare had made too familiar with slaughter and a vicious man.

Sir Steven Runciman, another respected historian of the crusades, summed up the two sides of Richards character: He was a bad son, a bad husband and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier. Richard spent his entire adult life in warfare and consistently displayed supreme physical courage, but gallant and splendid are not adjectives one would use today.

When writing of the past, it is a responsibility of historians to consult contemporary sources whenever possible, but also to weight them according to their authors relationship with the subjects of whom and the issues of which they wrote, and take into account the political and religious pressures on the chroniclers. In my biography of Richard the Lionhearts mother that extraordinary woman, Eleanor of Aquitaine, who was the target of calumnies and slanders in her own lifetime and afterwards it was vital to bear in mind that the contemporary sources in Latin were written by celibate and misogynistic monks. Even St Bernard of Clairvaux, the wise founder of the Cistercian Order, could not bear to look upon his own sister in her nuns robes. In addition to their aversion to all women as the perceived cause of mens lust, the chroniclers owed a political loyalty to either Eleanors French husband King Louis VII, whom she divorced, or Englands King Henry II, who locked her up for a decade and a half after she raised their sons in rebellion against him. The chroniclers were thus extremely unlikely to be objective about this major player on the European stage, and their comments on her must be assessed with that in mind.

Similarly, when evaluating King Richard I it is necessary to examine closely the enduring legend of this parfit gentil knight and noble Christian monarch who selflessly abandoned his kingdom in 1190 to risk all in performing his religious duty to liberate the Holy Land from the Saracen. In fact, the legend originated as a PR campaign orchestrated by Queen Eleanor to blackmail the citizens of the Plantagenet Empire into stumping up the enormous ransom demanded for his release from an imprisonment that was all of his own making and had nothing to do with religion.

Next page