Nigel Cawthorne has written numerous books on the myths and criminals of Britain. He lives in London. www.nigel-cawthorne.co.uk

Highlights from the Brief History/Brief Guide series

A Brief History of the Crusades

Geoffrey Hindley

A Brief History of the Druids

Peter Berresford Ellis

A Brief History of the Dynasties of China

Bamber Gascoigne

A Brief History of the Hundred Years War

Desmond Seward

A Brief History of the Private Lives of the Roman Emperors

Anthony Blond

A Brief History of Secret Societies

David V. Barrett

A Brief History of the Vikings

Jonathan Clements

A Brief History of the Universe

J P McEvoy

A Brief History of Middle East

Christopher Catherwood

A Brief History of the Kings and Queens of Britain

Mike Ashley

A Brief History of Henry VIII

Derek Wilson

A Brief History of Everyday Life in the Middle Ages

Martyn Whittock

A Brief History of Venice

Liz Horodowich

A Brief History of Mankind

Cyril Aydon

A Brief Guide to Greek Myths

Stephen Kershaw

A BRIEF HISTORY OF

ROBIN HOOD

NIGEL CAWTHORNE

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Constable

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2010

Copyright Nigel Cawthorne, 2010

The right of Nigel Cawthorne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication data is available from the British Library

UK ISBN: 978-1-84901-301-7

eISBN 978-1-47210-771-8

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

First published in the United States in 2010 by Running Press Book Publishers

All rights reserved under the Pan-American International Copyright Conventions

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system now known or hereafter invented, without written permission from the publisher

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Digit on the right indicates the number of this printing

US ISBN 978-0-7624-3851-8

US Library of Congress Control Number: 2009935107

Running Press Book Publishers

2300 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19103-4371

Visit us on the web!

www.runningpress.com

Printed and bound in the EU

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Some historians say that Robin Hood has no place in history, that he is a figure of myth made up by medieval balladeers. However, there are indications that such a person did exist and several real people may have contributed to the legend. There were undoubtedly a number of shady criminals inhabiting the forests of England in the Middle Ages who were called, or assumed the name of, Robin or Robert Hood, and a number of incidents in the tale of Robin Hood are borrowed from the lives of other outlaws of the time who are known to have been real.

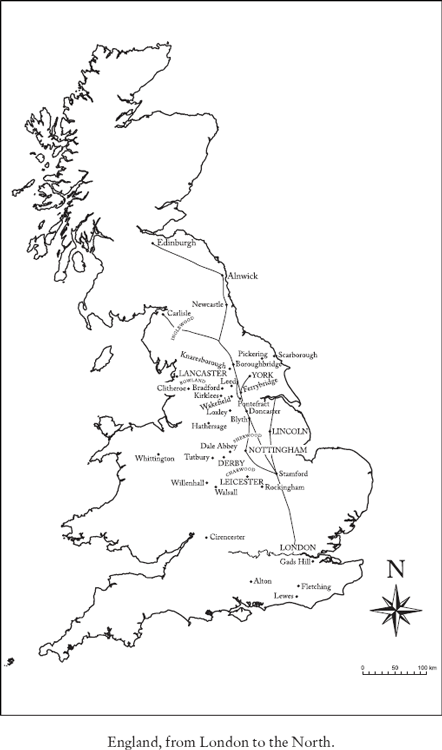

A number of kings who are certainly historic figures are mentioned in various versions of the tale. Nottingham did have a sheriff a series of them from 1068 on. There was a priory at Kirklees, where Robin is said to have died. And Little John, Friar Tuck and Will Scarlet can be linked to historical figures.

The story of Robin Hood also has a history of its own. In the earliest references, he appears to be merely a bandit, robbing travellers for his own survival or, perhaps, to enrich himself. But at the hands of the balladeers he is only interested in robbing those in authority, such as the sheriff or wealthy clerics. Those who were honest or poor were left largely unmolested.

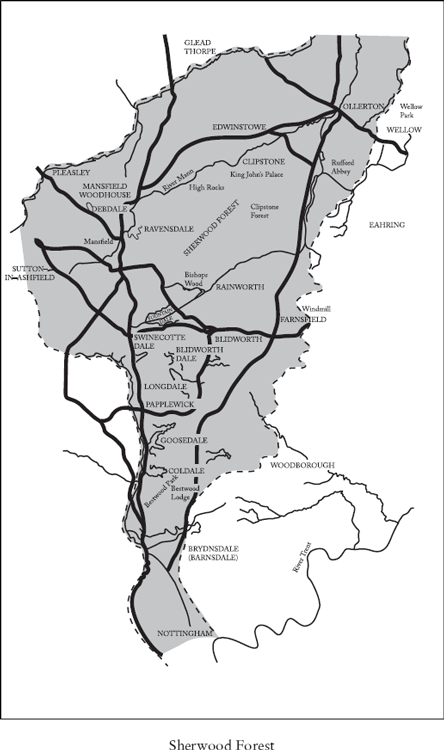

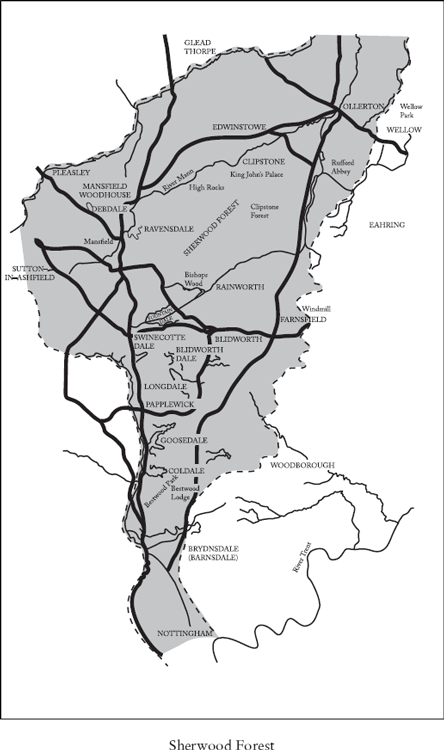

Robins major crime was poaching deer. This was seen as every freeborn Englishmans right, taken away from them by the Normans who brought the Forest Law with them from the Continent when they invaded in 1066. William the Conqueror himself was inordinately fond of hunting and cleared large areas of villagers and peasants to make way for the chase.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle says:

whosoever slew a hart, or a hind should be deprived of his eyesight. As he [Willson] forbade men to kill the harts, so also the boars; and he loved the tall deer as if he were their father. Likewise he declared respecting the hares that they should go free. His rich bemoaned it, and the poor men shuddered at it.

One of the areas he cleared was the New Forest in Hampshire. Like other deer parks, it was policed by Williams foresters who were employed to protect the game and anyone caught poaching was liable to lose their testicles as well as their eyes.

Things only got worse under Williams son William Rufus (10871100) and Henry I (110035) who, it was said, had an army of evil men to enforce the Forest Laws. And when Henry II (115489) became king, it was the custom for the royal foresters to be a complete law unto themselves, they put to death and mutilated whom they would without any trial whatever, or with but the mockery of the water-ordeal, a farce which had already been condemned by the church, but which was very fashionable with ruffians who were anxious to secure a conviction.

Matters came to a head when foresters seized a priest with the intention of extorting money from him. The Bishop of Lincoln threatened them with excommunication and they let him go. Afterwards, the Forest Laws were administered with something more nearly approaching justice.

Even so, the feudal lord still had absolute power over his family. Robert de Belesme, Earl of Shropshire and of Arundel and Shrewsbury, one of the most powerful and defiant barons of Norman times, tore the eyes out of his own children when they hid their faces behind his cloak in a game. He had his wife locked in fetters and thrown into a dungeon, only to have his servants drag her to his bed each night and return her to gaol in the morning. This was done to extort money from her family, but it can hardly have promoted marital harmony. Not that that would have mattered to Robert de Belesme. He refused to ransom his captives, preferring to have both men and women impaled on stakes. Even his friends were a little wary; he could be chatting away one minute then suddenly plunge his sword into someones side and laugh about it.

Robin and his Merry Men lived in these harsh times. In some of the ballads, they kill and maim without conscience. But, by and large, they embody the ideal of the stout yeoman, who drinks excessive amounts of ale and wine, and feasts on freshly killed venison.

The story of Robin Hood draws on history. It has had the feud between the Norman invaders and the Saxon inhabitants of old England thrust upon it. Prince Johns attempt to usurp his brothers throne while Richard was away fighting in the crusades was added later. Some have seen in the tale the rebellion of Simon de Montfort in 1265 or that of Thomas, earl of Lancaster, against Edward II in 1322. There are also echoes of Hereward the Wakes stand against Norman rule in 107071 and William Wallaces resistance to English rule in Scotland in 12971305.

Next page