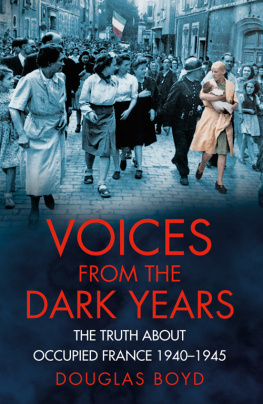

It is not surprising that few people in France wished to remember, let alone talk or write about, their experiences during the awful years of the German occupation of their country. I have to thank historian Robert O. Paxton, sometime professor of Columbia University, for breaking down the wall of silence in 1973 and forcing into the light of day many events that have since been investigated in greater depth.

On a personal level, my thanks are due to Max Lagarrigue, indefatigable editor of Arkheia magazine, for repeated access to information on the war years in south-west France; to Marie-Franoise Roth and her husband at Le Noirlac Hotel in St Amand-Montron for background on what did happen in the town where nothing ever happened; to Palu Fourcassi for an account of his time in Le Service de Surveillance des Voies; to Dde Fourcassi for persuading Marie-Rose Dupont to trust a historian she had never met before and talk about the terrible price she paid for the affair with her Austrian SS lover Willi, of which she had previously never spoken to anyone; to Joseph la Picirella for keeping alive the history of the Vercors betrayal a story that no one in France or the Allied countries wanted to be known; to Fabrice Vergili for sharing his research on the shame within the shame of the occupation the many thousands of French women who bore babies by German fathers and were publicly humiliated for this.

Many others who survived these years contributed but with the plea that their names not be revealed. Some asked this from guilt at what circumstances forced them to do and some from shame at what happened to them. Among the museums that contributed significantly are: le Muse de la Rsistance at Clermont-Ferrand; le Muse de la Poche at Royan; le Muse de la Rsistance du Vercors; le Centre Jean Moulin at Bordeaux; le Muse de la Rsistance at Limoges; le Muse de la Rsistance at Cahors. On a professional level, at The History Press, I have to thank Jay Slater for commissioning the book and editor Chrissy McMorris for pulling everything together and making a book out of a pile of paper. My personal thanks go to Jennifer Weller for help with maps and otherwise and, as always, to my partner Atarah Ben-Tovim who suffers with good humour the loneliness of living with a historian who is forever somewhere and sometime else.

Douglas Boyd

Summer 2012

CONTENTS

Abwehr: German military intelligence and counter-espionage organisation

Allgemeine-SS: the organisation headed by Himmler that ran the concentration and death camps

BCRA (Bureau Central de Renseignements et dAction): the Free French intelligence organisation

CDL (Comit Dpartemental de la Libration): committee in each dpartement coordinating Resistance actions before and during the liberation

CNR (Conseil National de le Rsistance)

COMAC (Comit dAction Militaire): action committee of MUR (see below)

COSSAC: Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander

deuxime bureau : French military intelligence

FAFL (Forces Ariennes Franaises Libres): Free French air force

FFI (Forces Franaises de lIntrieur): blanket term covering all Resistance and Maquis groups in build-up to, and during, the liberation

FTP (Francs-tireurs et Partisans): a communist Resistance movement

Kriegsmarine: German navy

malgr nous : term for Alsatians and Lorrainers compulsorily enlisted in German armed forces, meaning literally we had no choice

MAAF: Mediterranean Allied Air Forces

MAT (Manufacture dArmes de Tulle): arms factory in Tulle

Milice: paramilitary Vichy police force

MLN (Movement de Libration Nationale): successor to MUR

MUR (Movements Unis de le Rsistance): the first nationwide coordinating body of the Resistance

OAS (Organisation Arme Secrte): a Resistance movement headed by ex-army officers

OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht): German High Command

PCF (Parti Communiste Franais): French Communist Party

ORA (Organisation Rsistance Arme): Resistance movement headed by ex-army officers

OSS: United States Office of Strategic Services

PH: Purple Heart

SAARF: Special Allied Airborne Reconnaissance Force

SAS: British Special Air Service

Section F: department of SOE dealing with France

Section RF: department of SOE liaising with BCRA

SHAEF: Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force

SIS: Secret Intelligence Service, also known as MI6

Sipo-SD (Sicherheitspolizei/Sicherheitsdienst): German ultra anti-partisan troops

SOE: Special Operations Executive

SPOC: Special Projects Operations Centre

STO (Service du Travail Obligatoire): compulsory conscription for labour service in Germany

USMC: United States Marine Corps

Waffen-SS: the elite parallel German army controlled by Himmler, which carried out atrocities

PART 1

1

Tourists visiting France are often surprised by the number of Second World War memorials in towns and villages and beside country roads, dedicated to men shot by the German forces occupying the country in 194045 or deported in atrocious conditions to concentration and death camps in the Reich, from which the few who did return came back broken in health and spirit. Although many who suffered and died under the occupation have no memorial, the tourist wandering down a side street of a peaceful town, perhaps looking for a shady bar on a hot afternoon, is confronted far too often by a little shrine bearing the inscription Ici est tomb un maquisard , followed by a date in summer 1944.

Each of these shrines marks the spot where a young civilian usually male but sometimes a woman was gunned down by battle-hardened soldiers in German uniform, to die in a pool of blood with a parachuted pistol or Sten gun in hand. Even that word die is often a euphemism for a savage beating that ended with his or her body twisting on a rope hanging from a nearby tree or street lamp.

But who exactly were the maquisards and why were so many of them killed? And what exactly was the Resistance? Two clear generations after the tragedies to which the memorials bear witness, many French people ask themselves these questions, confused about the difference between the Resistance and the Maquis.

In the summer of 1940, after Hitler and his generals had taken just six weeks to conquer the country with the biggest standing army in Europe, the new government of Marshal Philippe Ptain signed an armistice agreement on 22 June. It was a humiliating defeat, after which a few patriots immediately sought to assuage the shame that their military and political leaders had been found so sadly wanting. In full knowledge that the penalty for being caught was death, they decided to work against the occupation in defiance of the armistice agreement signed by their legal government. A clause in the armistice agreement was quite explicit:

The French government will forbid French citizens to fight against Germany in the service of states with which the German Reich is still at war. French citizens who violate this provision are to be treated by German troops as insurgents.

Should they be caught, as many were, their own government would do nothing to help them. On the contrary, the Gestapo and German Security Police were aided and abetted by Vichys Police Nationale, Gendarmerie Nationale, the Milice and the Groupes Mobiles, including their Reserve, which was the ancestor of todays Compagnie Rpublicaine de Securit riot police.

In the First World War, which ended just over two decades before the defeat of 1940, France and the British Empire each mobilised between 8 million and 9 million men, but total French casualties were twice as high as those for the whole Empire. From a population of 40 million, France lost 1,357,800 men killed, with 4,266,000 wounded and another 537,000 taken prisoner or missing in action. At the other end of the scale, the decisive but late entry of the USA into that war cost only a total of 116,516 Americans killed and 206,502 other casualties.

Next page