Contents

Guide

OPERATION DRAGOON

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 Robin Cross

First Pegasus Books edition March 2019

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-860-0

ISBN: 978-1-64313-102-3 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

www.pegasusbooks.us

To the men of 36th Division

CONTENTS

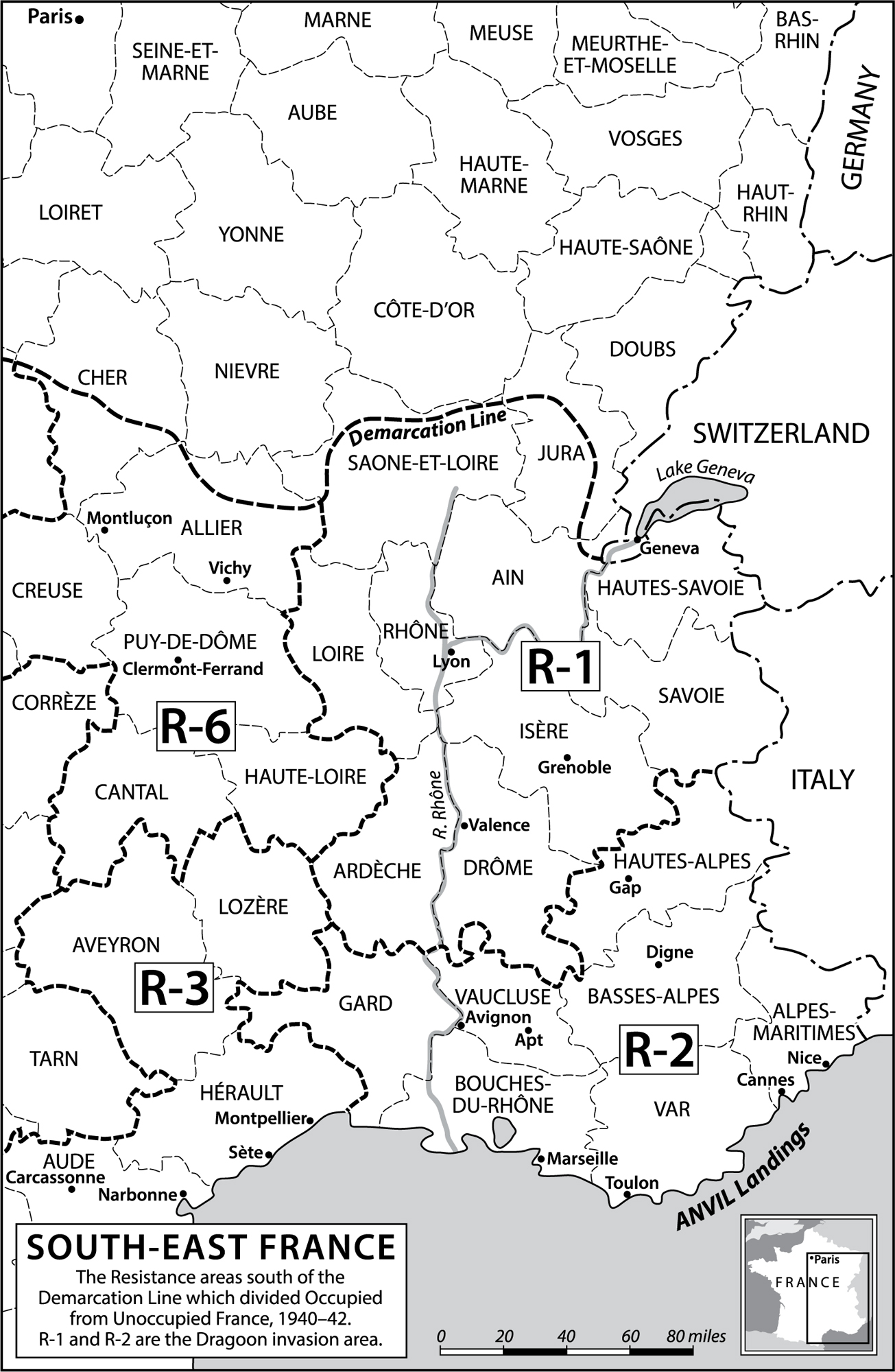

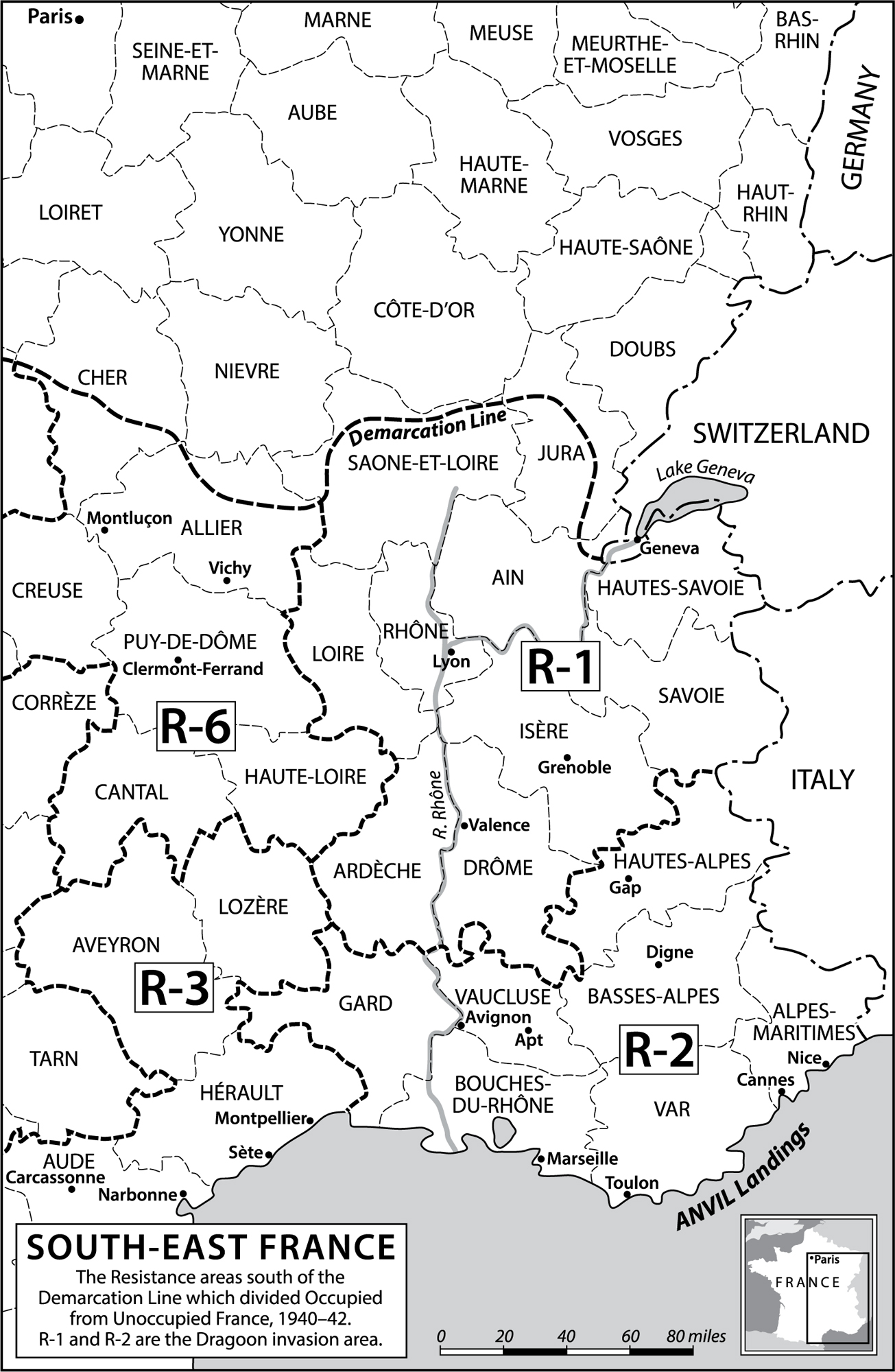

O peration Dragoon, the Allied invasion of the South of France, was for a long time overshadowed by Operation Overlord, the invasion of Normandy, which preceded Dragoon by over two months. However, in recent years the publication of a number of books has rekindled interest in Dragoon, which in John Keegans magisterial history of World War II occupies only a few lines. The genesis and gestation of Dragoon nevertheless throws an intriguing light on Anglo-American relations from the autumn of 1943 to the early summer of 1944, and reveals much about the tensions between the two high commands and their political masters during those critical wartime years.

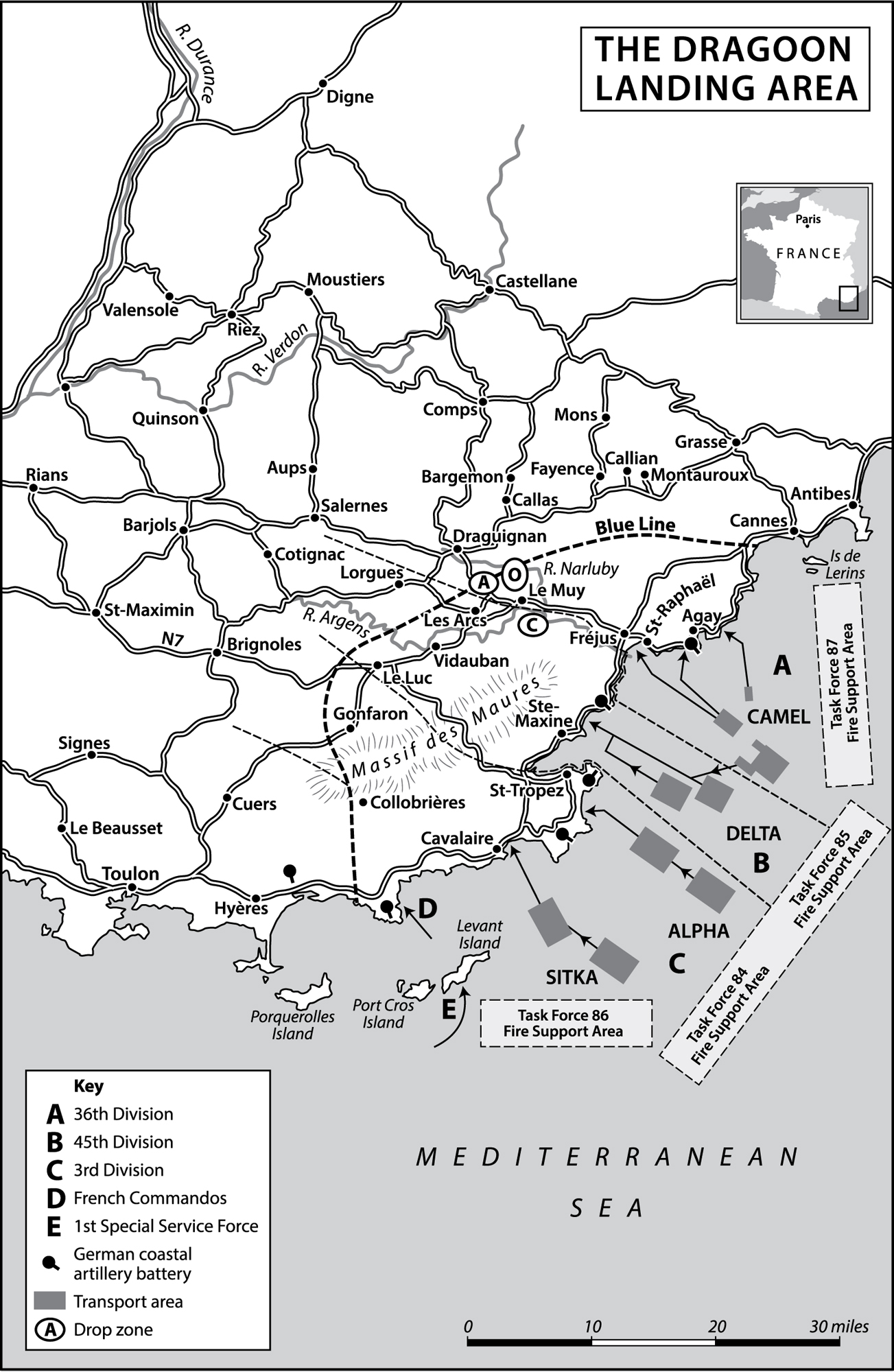

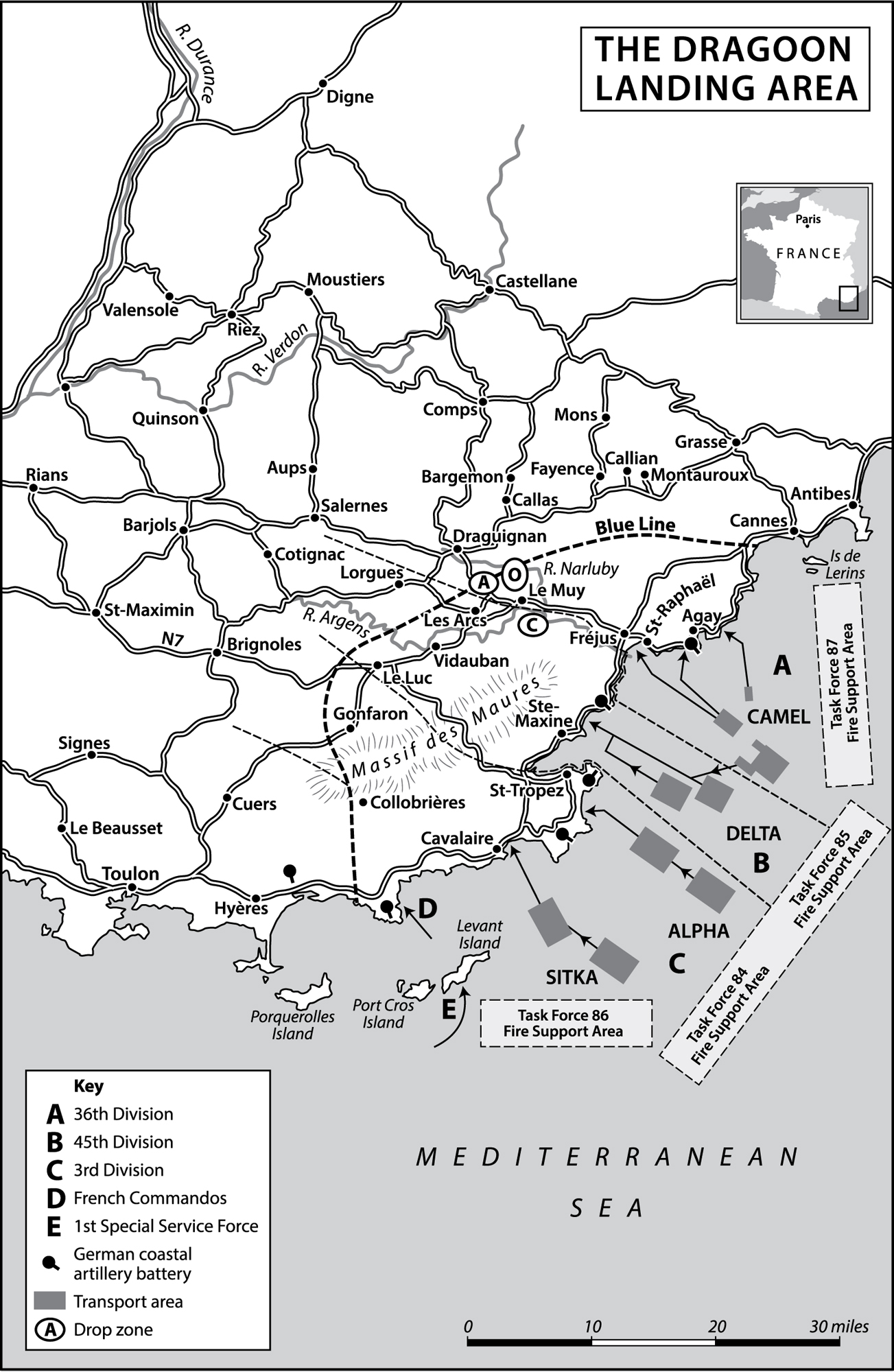

The British contribution to Dragoon, with the exception of the Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force, and a parachute brigade, was relatively slight. French participation, although vital for both military and diplomatic reasons, often proved problematic in the field, and tested the man-management skills of the American high command almost to destruction. The operations ultimate success depended, in the final analysis, on the flexibility of the U.S. Armys command structure operating in conjunction with its French allies and with the often highly irregular input of British and American special forcesrespectively, the Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). In a fast-moving campaign, the Allied cause was immeasurably helped by men like the OSSs Geoffrey Jones and SOEs Francis Cammaerts, and the remarkable agent Christine Granville. Their part in the Dragoon story, and that of the French Resistance, will receive the attention they merit. As part of this strand, a spotlight will focus on the significant role played in Allied decision-making by the interception and decryption of encoded German Enigma traffic, the so-called Ultra secret.

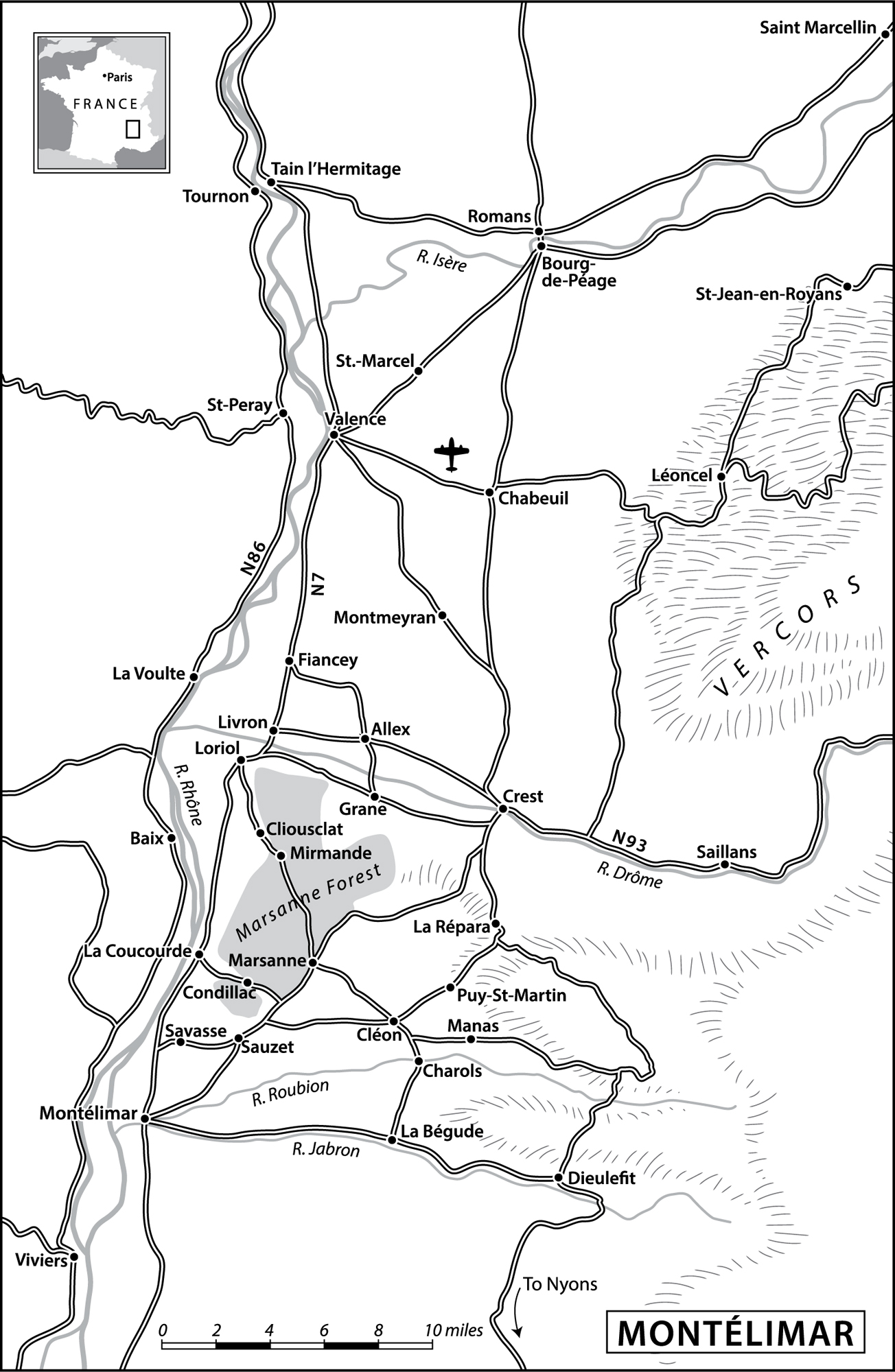

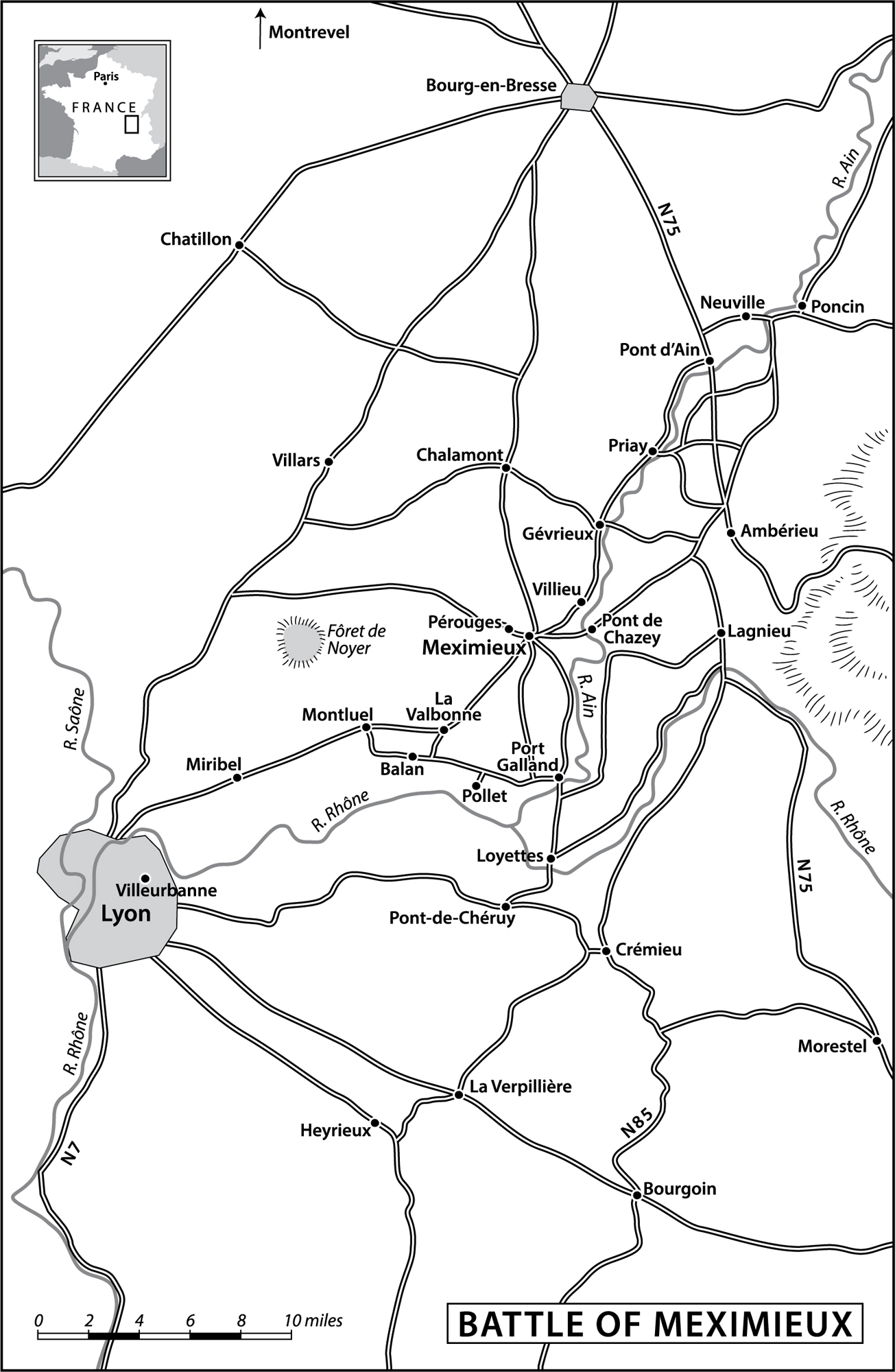

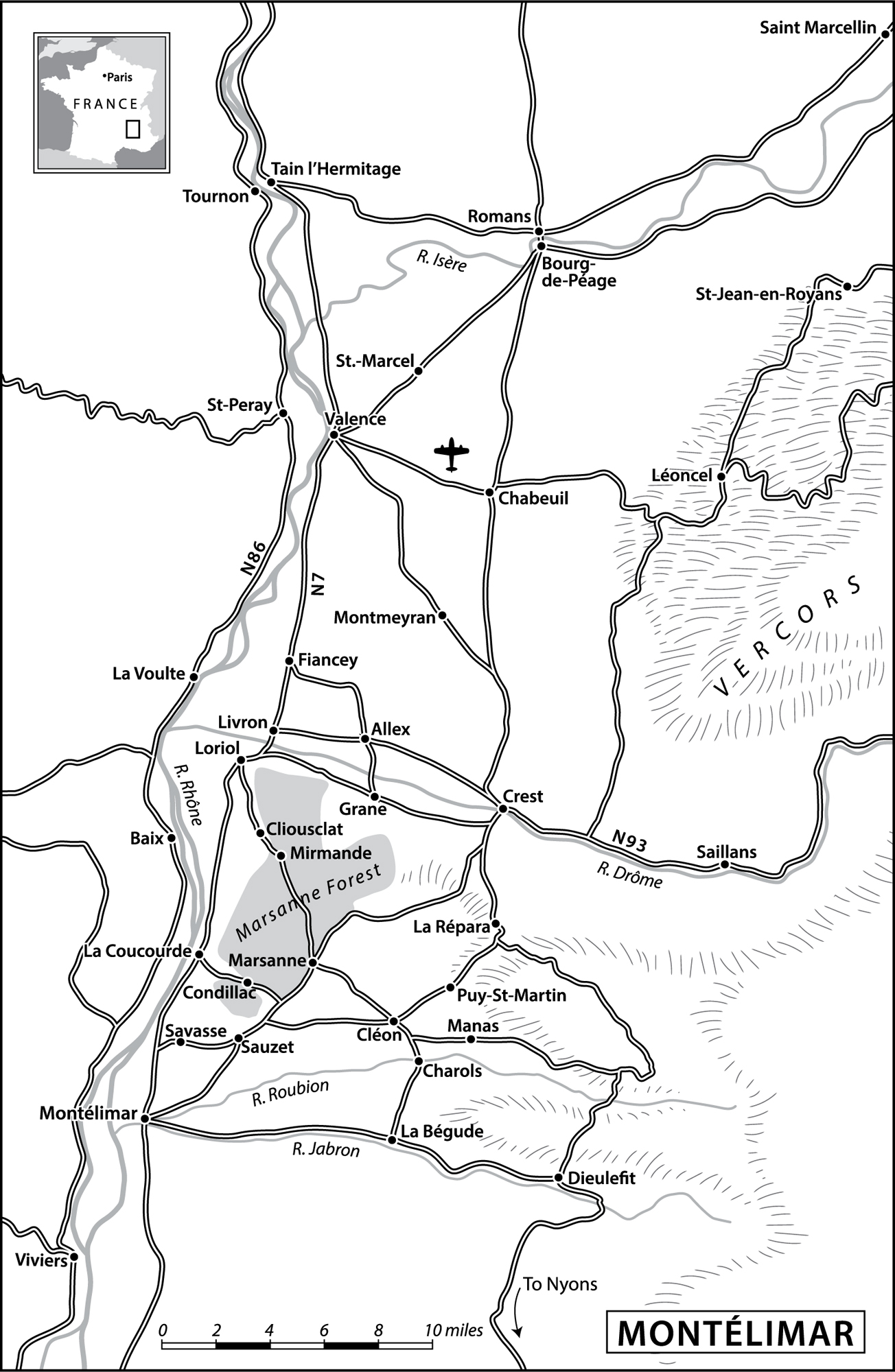

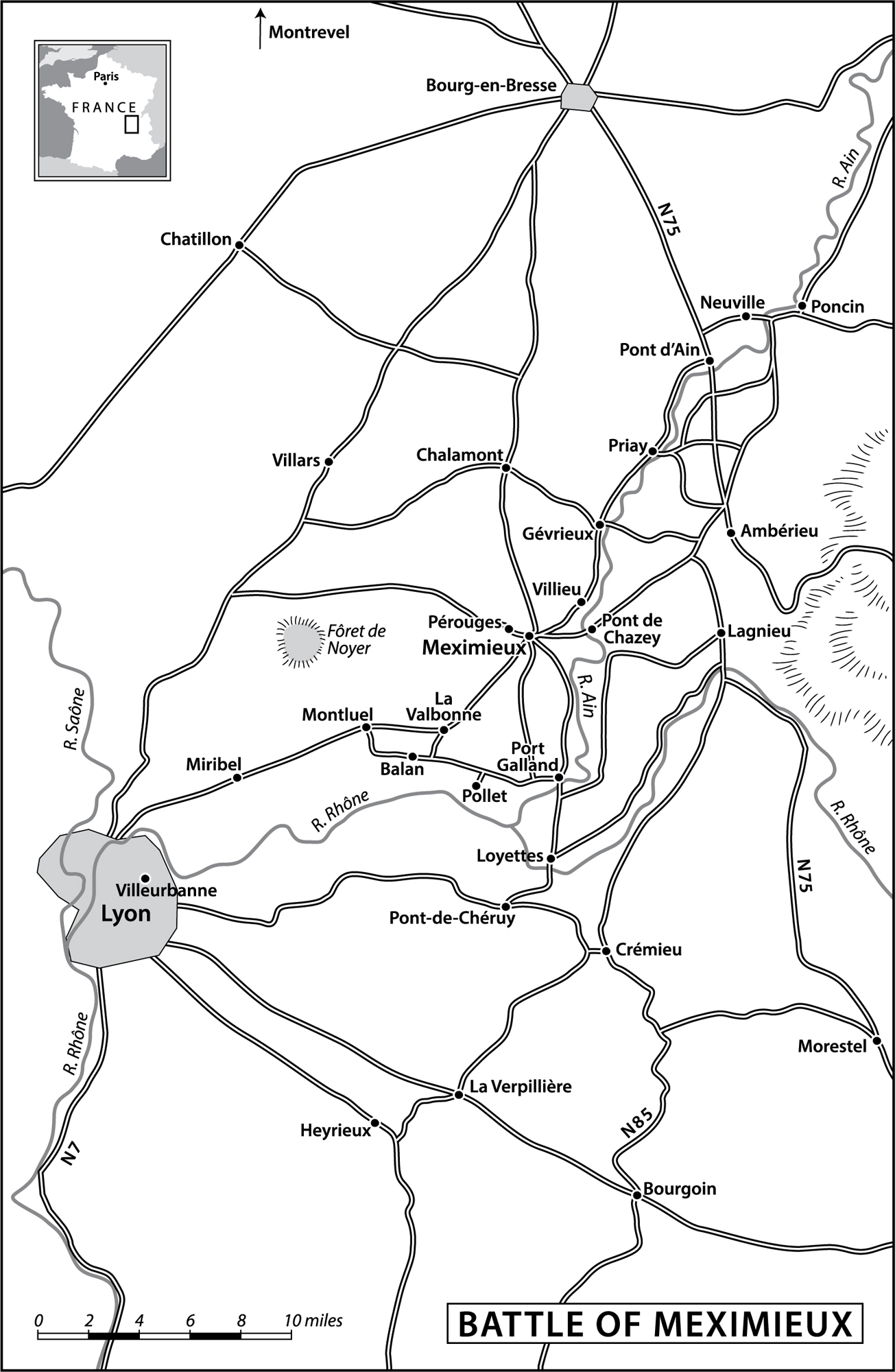

These elements, singly and severally, played a significant part in Operation Dragoon, alongside the key decisions made by Allied commanders like Generals Patch, Truscott, Devers, and Butler, and their subordinates. Generous space is also given to their German counterparts, among them Generals Blaskowitz, Wiese, and Wietersheim, who strove to prevent a serious reverse from descending into a rout during an epic withdrawal from the French Riviera through the eye of a needle at Montlimar and into the Vosges Mountains. The role of the ordinary soldierfrom grizzled German veterans of the Eastern Front to Texas farmboys and African Americans following the fighting on burial detailsis a constant theme, taking us from the landings on Riviera vacation beaches to the fogbound autumnal clashes in the Vosges Mountains that closed the curtain on Operation Dragoon.

Above all, Dragoon presents a panoramic picture of the military and industrial might, the greater part of it American, which hastened victory in the West: the logistics that lay behind it; the key decisions that secured it; and the personnel who made it happen. In writing this book I owe a great debt of thanks to the eminent historian Steven Zaloga, who supplied the illustrations and much advice, and Stephen Dew, who drew the maps. I would also like to thank another distinguished historian, Simon Dunstan, for his sound counsel throughout the project. Thanks are also due to the 36th Divisions archives in Austin, Texas, which yielded much detail on the course of the campaign from first to last. I am also grateful to Robert Maxham for his invaluable help in the 36th Division archives and to Jean-Loup Gassend for permission to quote material from his his Operation Dragoon, Autopsy of a Battle, The Allied Liberation of the French Riviera, AugustSeptember 1944 .

Robin Cross

Broxbourne, 2018

Sir, it is my duty to report that the Tunisian campaign is over. All enemy resistance has ceased. We are the masters of the North African shores.

Telegram from General Sir Harold Alexander, commander 18th Army Group, to Winston Churchill, May 13, 1943

T he period between November 1942 and August 1943 was, for Adolf Hitlers Germany, one of almost unmitigated disaster. It began with the Allied victory in North Africa at El Alamein in November 1942, followed five days later by the Anglo-American Torch landings in Morocco and Algeria, and continuing with the destruction of the German 6th Army at Stalingrad in February 1943. In May 1943, German and Italian forces in Tunisia surrendered to the Allies, and Admiral Dnitzs U-boat wolfpacks were withdrawn from the North Atlantic after suffering heavy losses. Two months later, in July 1943, the collapse of Operation Citadel, the summer offensive in the western Soviet Union by the German Army in the East ( Ostheer ), and the Allied invasion of Sicily, delivered a double body blow to the Third Reich. And finally, on the night of August 2 the last of four raids by the RAF Bomber Command concluded the Battle of Hamburg, during which, on the night of July 27, 729 bombers created a firestorm that engulfed four square miles of the eastern part of the city, prompting Hitlers minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, to describe the attack as a catastrophe, the extent of which staggers the imagination.

On July 19, 1940, flushed with victory in the Battle of France, Adolf Hitler had convened the Reichstag in the Kroll Opera House in Berlin to witness the creation of twelve field marshals. At the end of a long speech he told the assembled puppet deputies: In this hour I feel it to be my duty to appeal once more to reason and to common sense in Great Britain, as much as elsewhere. I consider myself in a position to make this appeal since I am not the vanquished begging favors, but the victor speaking out in the name of reason. I see no reason why this war should go on.

But it did go on, and in time Hitler acquired enemies vastly more powerful than the British. On January 30, 1943, in circumstances very different from those that accompanied his triumphal gesture of July 1940, Hitler created a single new field marshal, promoting Colonel General Friedrich von Paulus, commander of the German 6th Army encircled on the Volga in the Soviet city of Stalingrad.