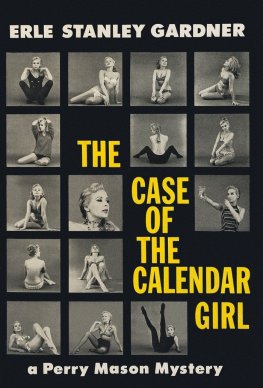

Erle Stanley Gardner

The Case of the Calendar Girl

I consider my friend, Dr. Hubert Winston Smith, one of the outstanding figures in the field of legal medicine, just as I consider legal medicine far more important than it is generally considered in the public mind.

Dr. Hubert Winston Smith is not only a doctor of medicine but an attorney at law as well. He is, moreover, a trial attorney of unusual ability.

Some years ago he was appointed special counsel to represent a veteran of World War II who had been convicted of homicide on circumstantial evidence and sentenced to the electric chair. Dr. Smith was able to bring out a mass of new evidence and present this evidence so convincingly that the conviction was reversed by the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Not only is Dr. Smith a professor of law, a teacher of evidence and of legal medicine at the Law School of the University of Texas, but he is also Professor of Legal Medicine in the Medical School of that University, and is Director of the Law Science Institute. In fact, it would take more space than is presently available simply to list Dr. Smiths honors and academic distinctions.

It is under his guidance that legal medicine classes for doctors and trial lawyers are being held throughout the country. In these classes, members of both the medical and legal professions are given an opportunity to study the highly technical field of medical evidence as applied to law.

But what interests me most of all about Dr. Smith is his philosophical outlook on life. This trained scientist feels that the time has come when man should concentrate on what Dr. Smith refers to as psychic income rather than income on a dollars-and-cents basis.

Recently I had occasion to visit a young man who was confined in jail on a charge that was almost certain to result in a prison sentence. This young man was making a good-faith effort to analyze the reasons which had caused him to become a criminal. At length, he said, I wish that while I was getting my education someone had pointed out to me a little more clearly the basic difference between right and wrong. This was a simple statement, yet when we analyze it, it has far-reaching repercussions. It was a statement that came from a young man whose life had been blasted because he hadnt stopped to think of the basic difference between right and wrong.

Dr. Hubert Winston Smith is a man at the other end of the human spectrum. He is as highly educated as any man can expect to be. He is a master of all branches of medicine, including that of psychiatry. He is a shrewd, ingenious, well-trained, capable trial attorney. He is one of the outstanding educators in the field of legal medicine, and his life is devoted to increasing the field of human knowledge.

And Dr. Smith feels that it is time for us as a nation to pay more attention to psychic income.

So I dedicate this book to my friend:

HUBERT WINSTON SMITH, A.B., M.B.A., LL.B., M.D.

Erle Stanley Gardner

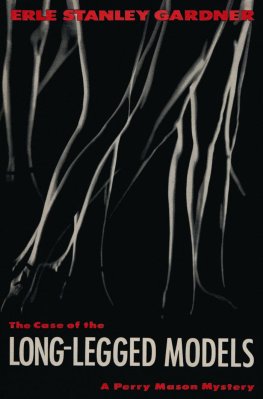

George Ansley A building contractor who met trouble when he set a steel beam an inch off specifications. He had an eye for gals with gams, but he called upon Perry Mason when he couldnt size up a shoe-switching gimmick

Meridith Borden An arrogant public-relations man who lived behind barbed wire. He took cheesecake snapshots for kicks, but he didnt spend all his time in the darkroom

Perry Mason A sharp-witted attorney who was reluctant to take on a case that had no murder strings attached. He pulled his usual legal pyrotechnics once he entered a preliminary hearing

Della Street Masons confidential secretary was told to take a day off. She needed a rest after a calisthenic bout with a Doberman pinscher

Paul Drake A tall, quizzical private detective who had a nose for little white lies. He was willing to help Mason as long as things were on the up-and-up

Beatrice Cornell An ex-photographers model who ran a catchall telephone service. She could round up models in short order, especially those with tell-tale bruises

Dawn Manning A gray-eyed picture of innocence who sometimes posed with a chaperon. She was defended by Perry after he had first sold her down the river

Lieutenant Tragg A Homicide chief who chose eating places by his modus operandi. He joined Mason for a meal, an incident that wreaked havoc with his diet

Loretta Harper A chestnut-haired model who affiliated with unofficially divorced men. She had trouble proving her identity after she had taken such pains to falsify it

Frank Ferney Meridith Bordens general assistant was an ideal answer man. He knew all the angles, including impersonation over a house-to-gate phone

Margaret Callison A comely veterinary who had little interest in Meridith Bordens activities. She concerned herself with his animals, especially his watchdogs

George Ansley slowed his car, looking for Meridith Bordens driveway.

A cold, steady drizzle soaked up the illumination from his headlights. The windshield wipers beat a mechanical protest against the moisture which clung to the windshield with oily tenacity. The warm interior of the car caused a fogging of the glass, which Ansley wiped off from time to time with his handkerchief.

Meridith Bordens estate was separated from the highway by a high brick wall, surmounted with jagged fragments of broken glass embedded in cement.

Abruptly the wall flared inward in a sweeping curve, and the gravel driveway showed white in Ansleys headlights. The heavy iron gates were open. Ansley swung the wheel and followed the curving driveway for perhaps a quarter of a mile until he came to the stately, old-fashioned mansion, relic of an age of solid respectability.

For a moment Ansley sat in the automobile after he had shut off the motor and the headlights. It was hard to bring himself to do what he had to do, but try as he might, he could think of no other alternative.

He left the car, climbed the stone steps to the porch and pressed a button which jangled musical chimes in the deep interior of the house.

A moment later the porch was suffused with brilliance, and Ansley felt he was undergoing thorough, careful scrutiny. Then the door was opened by Meridith Borden himself.

Ansley? Borden asked.

Thats right, Ansley said, shaking hands. Im sorry to disturb you at night. I wouldnt have telephoned unless it had been a matter of considerable importance at least to me.

Thats all right, quite all right, Borden said. Come on in. Im here alone this evening. Servants all off... Come on in. Tell me whats the trouble.

Ansley followed Borden into a room which had been fixed up into a combination den and office. Borden indicated a comfortable chair, crossed over to a portable bar, said, How about a drink?

I could use one, Ansley admitted. Scotch and soda, please.

Borden filled glasses. He handed one to Ansley, clinked the ice in his drink, and stood by the bar, looking down at Ansley from a position of advantage. He was tall, thick-chested, alert, virile and arrogant. There was a contemptuous attitude underlying the veneer of rough and ready cordiality which he assumed. It showed in his eyes, in his face and, at times, in his manner.

Ansley said, Im going broke.

Too bad, Borden commented, without the slightest trace of sympathy. How come?

I have the contract on this new school job out on 94th Street, Ansley said.

Bid too cheap? Borden inquired.

My bid was all right.

Labor troubles?

No. Inspector troubles.

How come?

Theyre riding me all the time. Theyre making me tear out and replace work as fast as I put it in.

Whats the matter? Arent you following specifications?

Of course Im following specifications, but it isnt a question of specifications. Its a question of underlying hostility, of pouncing on every little technicality to make me do work over, to hamper me, to hold up the job, to delay the work.

![Erl Gardner - The Case of the Deadly Toy [= The Case of the Greedy Grandpa]](/uploads/posts/book/924181/thumbs/erl-gardner-the-case-of-the-deadly-toy-the.jpg)