Sign up here to receive updates about free books as we publish them.

Dante (1265-1321)

The Divine Comedy

But already my desire and my will

were being turned like a wheel, all at one speed,

by the Love which moves the sun and the other stars. Dante, The Divine Comedy

One of the surest signs of fame among is to be known solely by ones first name, with the mention of just that first name making clear who is being spoken of. So it is with Dante Alighieri (1265-1321), known simply as Dante thanks to the success of the Divine Comedy, one of the seminal works in Western literature. With Divine Comedy, Dante is often considered the master of contemporary Italian, as well as a forerunner of the Renaissance, which began to flourish in Florence around the same time. The Divine Comedy tells of Dantes journey through Hell (the Inferno), Purgatory, and Paradise, guided by famous poets including Virgil. Dantes epic discusses religion, philosophy, and a wide range of subject matter throughout his travels.

Dante took nearly 13 years to compose the Divine Comedy, all the while living in exile from his home city of Florence, and the work influenced just about every important writer any literary scholar can name, among them, Boccaccio (1313-75); Chaucer (circa 1344-1400); John Milton (1608-74); William Blake (1757-1827); Victor Hugo (1802-85); Joseph Conrad (Teodor Josef Konrad Korzeniowski) (1857-1924); James Joyce (1882-1941); and Ezra Pound (1885-1972). One of the greatest poems in English, T.S. Eliots The Waste Land, is in many ways derivative of Dante.

Dante Alighieri, especially when one considers his time and environment, was bold and fearless, following the calling and mission of the artist in the purest sense. He not only took his contemporaries to task in an enormous fashion, he also embraced the timeless challenges that metaphysical questions present. Dante had the nerve to force his reader to question lifes toughest mysteries, and offer at least one possible blueprint for redemption. His mind, his language and his contributions to art, culture and intellect remain unsurpassed.

Everything You Need to Know About the Divine Comedy is a comprehensive guide that provides a synopsis, a description of the characters, and a summary and analysis of every chapter. You can use this as a guide while you read or as a way to brush up on everything you once knew and since forgot.

Things to Know about Dante

Michelinos fresco depicting Dante holding a copy ofDivine Comedynext to the entrance to Hell, the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory and the city of Florence, with the spheres of Heaven above

- Dante is considered one of the greatest, if not the greatest, poet epic or otherwise of all time. The magnitude of his most major work, The Divine Comedy, is unsurpassed; however, what also sets him apart from his literary rivals is that the Tuscan dialect in which he wrote became Italys national language. Further, he paved the way for poets to write in the vernacular, choosing his dialect over Latin, the language of the Church, the State and epic poets who preceded him. Even Shakespeare in all his genius did not have this level of influence on his language, English, which he, for all intents and purposes, inherited.

- Dante is credited with advancing, if not truly creating the poetic technique of terza rima, which is an interlocking three-line rhyme scheme. Most notably, Chaucer borrowed the technique for The Canterbury Tales.

- The Divine Comedy is steeped in theological references, even in structure: it is made up of three parts, each with 33 cantos. Three is extremely symbolic in Christianity, due to the belief in the Holy Trinity God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit. Thirty-three is also very significant, as this is the age at which Jesus was crucified.

- Inferno has 34 cantos, but the first in considered an introduction.

- Although exiled from his city of Florence for the last nineteen years of his life, Dantes loyalty never waned. He always considered himself not an Italian, not a Tuscan, but a Florentine until the day he died.

- Dantes exile was due to his political leanings, and specifically, the Florentine GuelphGhibelline conflict. He intended the Divine Comedy to be something of a platform to share his belief in what was fundamentally the separation of church and state, and point the finger at corrupt leadership, both political and religious.

- Dante placed himself at the center of the Divine Comedy as the Pilgrim. Even though characters certainly reflect a writers position and/or beliefs, and may display many of their creators own personal traits, few writers have been so bold as to employ this literary technique.

- There is a school of critics that believes Dante suffered from an over-inflated sense of importance well beyond that of an artist. Instead, it has been argued by scholars that he considered himself worthy of being included in the elevated category of prophet, as The Divine Comedy tackles enormous metaphysical and religious themes, and offers a redemptive path for sinners to follow.

- Each of the three canticas that make up The Divine Comedy - Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory) and Paradiso (Paradise, or Heaven) - ends in the word stelle (stars).

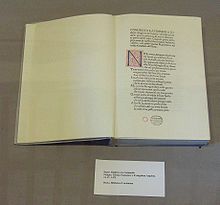

- No original copy of Dantes masterpiece survives today, but many priceless copies do exist. The first printed copy dates back to the late 1400s.

In many ways, The Divine Comedy serves as a handbook to the Middle Ages and the trends of thought it advanced. Dantes work touches upon the scientific, political, and spiritual tenets of the day, with real life references to some of his own contemporaries, to historical figures that played a part in the development of western civilization as a whole.

Look at any diagram or map available that corresponds to the Hell, Purgatory and Heaven of the poem and you will find incredibly studied details that reflect the science of the times. Dante incorporates many of the ideas that were considered fact by his period. His outline of how each place stands in its relation to each other tries to acknowledge all available knowledge of the sun, moon, stars and planets. Not satisfied to keep these tenets contained within their own parameters, he extends his questions to the more mysterious, blending theology with science by asking such things as why do people exhibit such drastic differences in mindsets and beliefs, or what happens to us when we die, or is sin material. These probing questions would have great appeal to his contemporary audience, and frankly, still do today.