This book made available by the Internet Archive.

VJ

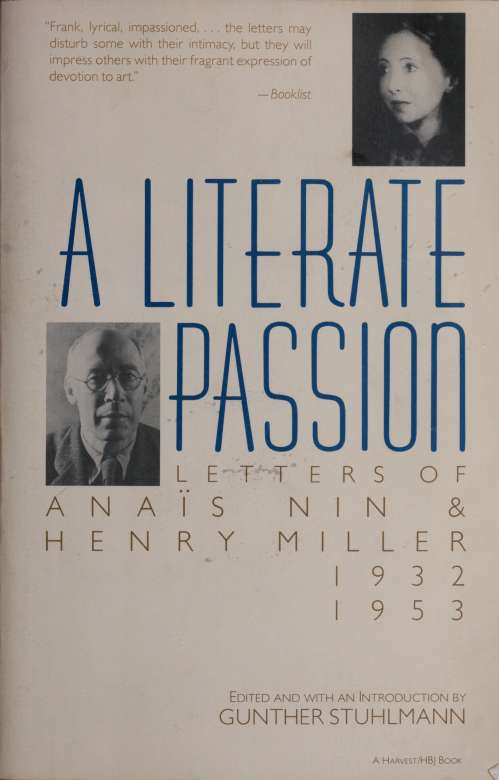

Miller wrote to Anais Nin in February 1932. "I shall never catch up. It is why, no doubt, I write with such vehemence, such distortion. It is despair." A few months later Anais Nin noted in her diary: 'The same thing which makes Henry indestructible is what makes me indestructible: It is that at the core of us is a writer, not a human being."

Until the recent publication of Henry and June, a volume drawn from previously suppressed diary material, most of what we could glean of their relationship came from the edited pages of the published Diary of Anais Nin y the seven volumes spanning the years 1931 to 1974. Henry Miller, shortly before his death at eighty-nine, in 1980, had brought out some brief, revisionist reminiscences of Anais Nin in a collection portraying some of his female friends. But in his earlier published work, for all its seemingly self-revelatory frankness, there is little evidence of their long romance, their turbulent involvement, unless one tracks down emotions and incidents Miller has transposed into a different time and place: to the New York of the 1920s, into the saga of his "Rosy Crucifixion."

We have also had available to us, of course, the volume of Henry Miller's Letters to Anais Nin (New York: G. P. Putnam, 1965). At the time of its publication, he had finally won the battle against a Puritanical censorship which for almost thirty years had kept his most important books from being published in his own country. It was the start of a still rather reluctant rehabilitation of his image as a mere woman-degrading pornographer. The focus of the volume was on Miller's development as a serious writer. Anais Nin, then almost exclusively known for her "avant-garde" fiction, appeared only as the silent recipient of a torrent of letters, as the confidante with whom he seemed most comfortable. The intimate aspects of their relationshipas in the diary volumes published thereafterhad to be omitted.

Thus it is in the letters presented here, covering more than twenty years, that we have for the first time a two-voiced, kaleidoscopic record of two writers in lovein love with each other, for a time, but, above all, in love with writing.

For Anais Nin, since the age of eleven, writing had been the only way she knew of gathering in her emotionally splintered life following her father's desertion of the family. Possessed by a terrifying, self-observing consciousness, she felt separated from the "real" world and fragmented by unrealized potentialities. ("No wonder I am rarely natural in life. Natural to what, true to which condition of soul, to which layer? How can I be sincere if each moment I must choose between

Vll

five or six souls?") The diary had been her refuge, her workshop, and the act of writing her only stabilizer. 'The journal is a product of the disease, perhaps an accentuation and exaggeration of it. I speak of relief when I writeperhapsbut it is also an engraving of pain, a tattooing on myself, a prolongation of pain."

The diary long sufficed as her all-accepting friend, the comforting repository of her confidences. But by the time she had escaped from the courtships of her unimaginative Spanish-Cuban admirers into marriage to the "poetic" and handsome young Scotsman Hugh (Hugo) Guiler in 1923, she had also realized that to become a writer she had to emerge from the sheltering secrecy of her diary. In the early 1920s she worked on novels and stories, initially to be publicly recognized as an artist (like her beloved father) and later also to achieve a modicum of financial independence. From the start she had the steady support of her husband. She received encouragement from her brother Joaquin, and from her cousin Eduardo Sanchez (the first great infatuation of her girlish years), who eventually had come to live in Paris. But all her dogged attempts to succeed as a writer proved futile. In the diary her writing always flowed freely, unselfconsciously. When she tried to be "professional," when she faced an amorphous, uncaring world "out there," something, she felt, was missing. "I am terrified of my conscious work," she concluded in 1932, "because I do not think it has any value. Whatever I do without feeling has no value." What Anais Nin cherished most, in life and in art, it seems, was "feeling."

One might say, in fact, that the first two items she managed to get printed emerged from an overflow of her feeling. "The Mystic of Sex" (an essay on D. H. Lawrence published pseudonymously in The Canadian Forum, in October 1930), and its offspring, the "Unprofessional Study" of D. H. Lawrence, published in 1932, reflect her own urgent needs to express her sexuality, to reorder the framework of her marriage, as much, perhaps, as they were a passionate defense (the first by a woman) of a much maligned fellow artist. Indeed, one might regard them as the first successful attempts to transform details of her private agonies into "created" works that could be displayed publicly without the danger of causing hurt or injury to people she loved and respected.

"Have begun to open [the] diary and let it be read, to realize it's my major work, and seeking to solve the human problems of its publication," Anais Nin wrote to Miller in late 1953. We know that another dozen years went by before this enormous projecta constant theme

Yin

throughout these lettersbegan to be realized. But even then, in 1966, Anais Nin had not found a solution to the "human problems." All she could do, at the risk of distortion and fragmentation, was to exclude from this lifelong record of her self-creation certain aspects that had been vital to her formation as a woman and as a writer: her marriage, her erotic adventures, and the depth of her involvement with Henry Miller. "To tell the truth," she had written, "would be death dealing."

At the heart of her concern, quite obviously, was the man she had married so enthusiastically, so idealistically in 1923, and to whom she remained linked until her death in January 1977. "My loyalty to Hugh is easily definable," she wrote in November 1932, at a time she already felt compelled to hide the handwritten volumes of the diary from her husband. "It consists in not doing him harm." It was a stance she would assume for the rest of her life. While she was able to slip with seeming ease across the conventional boundaries of her marriage, without any apparent sense of guilt ("There is no American virginal attitude toward sex in me"), a deeper loyalty, beyond mere self-preservation, prevented her from publicly exposing her husbandor anyone elseto her laby-rinthian secrets. "He is among all of us the one who knows best how to love," she had written of Hugo, late in 1932, "... a vastly generous, warm man who has kept me from misery, suicide, and madness."

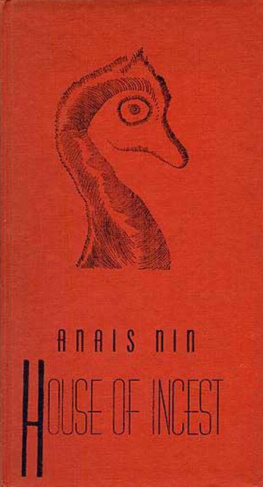

In her published fiction, which emerged not without difficulty from the emotional compression chamber of her diary, Anais Nin could disguise biographical facts, the truth told "as a fairy tale"as she clued in readers of her first book of poetic prose, The House of Incest, in 1936. But when publication of the diary itself finally approached there was no way of transforming essential details into a "dream." They had to be omitted, suppressed.