Introduction

Forbes has obsessively tracked the wealth of Americas richest people for the past 33 years. Its never been easy to get multimillionaires and billionaires to open upfew want the secrets of their success revealed to their competitors and the public, and fewer still want their finances out in the open. But we strongly believe in disclosure and transparency. In tracking American wealth, we are not only tracking Americas great fortunes but its businesses, cultural leanings and sociopolitical issues. Forbes follows these billionaires because following the money is crucial to understanding how America operates.

Properly valuing these fortunes has never been easy. After all these years and experience, the task remains a herculean effort. Forbes reporters comb through a list of 600 or so strong candidates and then start the difficult labor of sifting the richest from the merely wealthy. Whenever possible, reporters sit down with potential Forbes 400 members in person. Employees, attorneys, handlers, competitors, analysts and more offer their expert opinions to accompany the research our wealth team does. That includes poring over thousands of SEC filings and disclosures, court and probate records, federal financial disclosures, and Web and print articles. Forbes looks at all assets: holdings in public and private companies; real estate; planes, trains and automobiles (or more appropriately, yachts, planes and Lamborghinis); vineyards; art collections; car collections and more. We take debt into account as well. After all, their business partners, counterparties and investors certainly do before conducting business with them. We never assume or profess to know what lies on a billionaires personal balance sheet, though some 400 members do provide information to that effect.

In structuring this collection of the best writing to appear in Forbes 400 issues over the years, we noticed a few themes that naturally emerged. There were stories of entrepreneurs and strivers who had pursued and ultimately found their callings. For some, like Hobby Lobbys David Green, that calling is distinctly religious. For others, like Spanxs Sara Blakely, they embody a purpose of character and sureness of vision that, with the benefit of hindsight, transform their stories into nothing less than the successful pursuit of the American Dream. Billionaires, of course, are no exception to eccentricity as well, and several stories showcased in the following pages profile larger-than-life personalities, like Stewart Rahr, the self-professed Number One King Of All Fun. Some pieces had a timeless quality to them, and crystallized many of the themes that recur when reporting on the incredibly rich: The subjects of these stories exhibit entrepre-neurial spirit, exploit marketplace gaps, create new markets, compete against entrenched interests and so on. In other words, these stories were and remain classics.

To supplement these longer profiles, we showcase the clipped but magisterial tone found in the paragraph-long files written for each 400 member over the years. Youll find that the best of these briefs on notable rich listers range from the inspiring to the astounding, like the case of one member allegedly living as a fugitive on a yacht equipped with guided missiles in 1982. The Spotlight On sections sequentially feature files for some of Americas most iconic billionaires that track their ascents across the great arcs of their careers. Its a unique way to read about the rise of business visionaries like Steve Jobs and George Soros, as it happened and in the context of their lifework.

The business of the rich is the publics business. Each year The Forbes 400 helps bring to light what Americas richest people have done to amass their considerable fortunes, and it serves as a great proxy for the state of business in America. If you want to know how the world works, a good place to start is at the top.

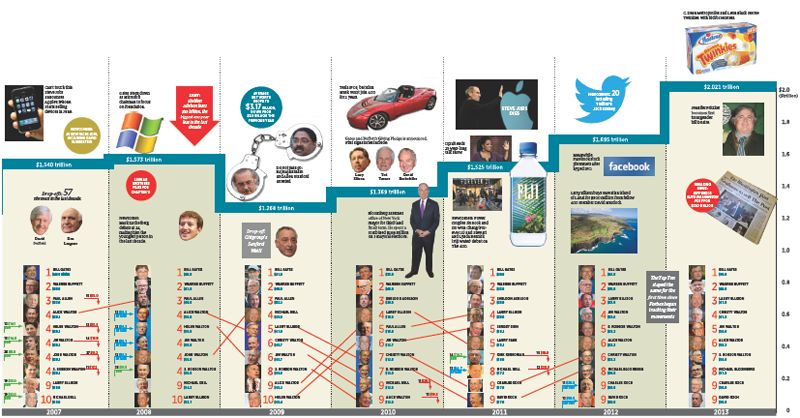

TRILLION-DOLLAR YEARS

From the release of the iPhone in 2007 to the first transgender billionaire in 2013, the Forbes 400 have added powerful newcomers while the top 10 have played an exclusive game of musical chairs.

MUST I BE A SAINT?

BY DANA WECHSLER LINDEN

This feature appeared in the 1990 Forbes 400 edition.

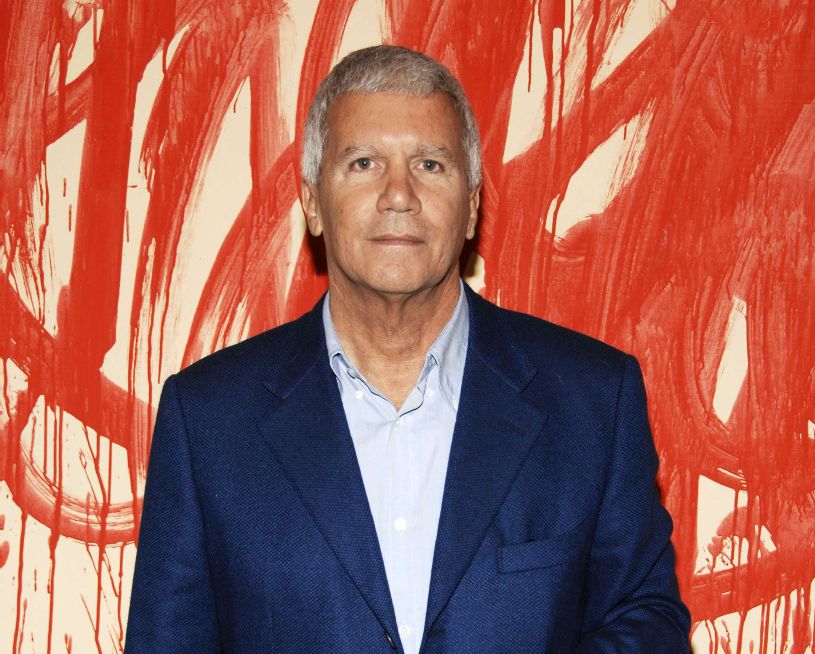

Larry Gagosian

BILLY FARRELL/PMC/SIPA/NEWSCOM

EVEN AS HE HAWKED $5 POSTERS of kittens and seascapes on a sidewalk near UCLA in the mid-1970s, Larry Gagosian thought big. His poster supplier offered more expensive graphics; soon Gagosian was selling $100 limited edition museum posters signed by such prolific artists as Roy Lichtenstein and Picasso. About a year later he opened an art gallery and was selling $5,000 paintings to centimillionaire real estate developer Eli Broad and cold-calling dozens of other wealthy art collectors.

Larry always had grandiose aspirations, even when he didnt have two dimes to rub together, recalls Los Angeles collector Ira Young, who occasionally lent money to Gagosian and later wound up taking legal action against him. He talked about dealing in Picassos and Renoirs, and conquering the New York art world. He said art was just a commodity, like any other.

Agrees Michele De Angelus, curator for Eli Broad: Dealing used to be a gentlemanly pursuit. Larry unabashedly wanted to make money.

Gagosianknown by friends and critics alike as Go-Godoes not deny that he is a quick-witted trader who rode the great 1980s bull market in art prices to the top of the art world. But he is quick to label as sour grapes the claims of many art dealers that his aggressive dealing tactics have somehow corrupted the art business. Asks Gagosian acidly: Is it written somewhere that only Sothebys and Christies should profit from the resale of art, and that everyone else should be some kind of saint?

Now 43, Gagosian resides on New Yorks Upper East Side in his landmark carriage house, complete with first-floor lap pool; its former owner was Schlumberger heiress Christophe de Menil. He is chauffeured around the city in one of his two Mercedes. He confirms he is about to buy a posh oceanfront estate on Long Islands South Fork built by Francois de Menil, valued by local real estate agents at upwards of $5 million.

Raised in modest circumstances in Los Angeles, Gagosian achieved all this by changing the rules of the modern art business. Traditionally, dealers in contemporary art were a combination of agent and principal. Dealers such as Leo Castelli, who discovered Jasper Johns, searched for young artists they thought would be the stars of their generation. The dealer/principals sponsored the young artists and promoted their work over the years. In this they were similar to the venture capitalists and Wall Street houses that underwrite young companies.

The traditional approach requires time, patience and capital, little of which Larry Gagosian had. But he did have prodigious energy, and he shrewdly grasped that the contemporary end of the art market lacked liquidity: If a collector wanted to sell a painting, he was at the mercy of the established dealers and auction houses. Likewise, if a collector wanted a particular painting, he had to wait until its owner decided to sell.