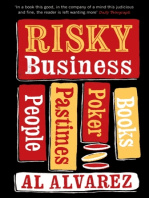

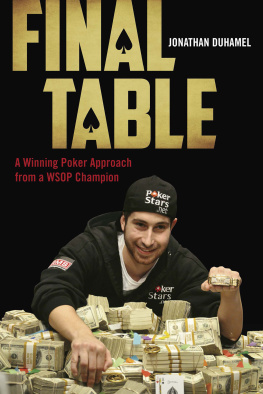

THE BIGGEST GAME IN TOWN

AL ALVAREZ

_ocr_0003_001.jpg)

First published in Great Britain 1983

Copyright Al Alvarez

This electronic edition published 2010 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Al Alvarez to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-40880-663-0

www.bloomsbury.com/alalvarez

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

N INE O'CLOCK on a Tuesday morning at the end of April 1981, and according to the giant illuminated figures at the top of the Mint Hotel the temperature was already ninety-two degrees. At the entrance of Binion's Horseshoe Casino stood the famous horseshoe itself, seven feet high, painted gold, and enclosing within its arch a million dollars in ten-thousand dollar bills. The hundred bills are neatly ranked and held, for whatever foreseeable eternity, in some kind of super-perspex bulletproof, fireproof, bombproof - the perennial dream of the Las Vegas punter visible to all, although not quite touchable. If you come too close, one of Binion's giant security guards, leather straps polished and creaking over his beige uniform, gun in his holster, moves quietly forward.

The million-dollar horseshoe reflected the glare of the morning sun on Fremont Street. Behind it were gloom and movement: a long, low, rather shabby room, full of noise and smoke, and, unlike the other casinos at this early hour, full of people. Women in halters and men in cowboy boots and Stetsons jostled each other around the roulette and craps tables, rattled the armies of slot machines, and perched in semicircles before the blackjack dealers; even the seats in the little keno lounge were mostly taken. At the back, there was already a crowd along the rail that separates the casual punters from the area that, for five weeks every year in the last decade, has been set aside for poker.

Fixed to one wall of this makeshift poker room was a large yellow banner, announcing in red, BINION'S HORSESHOE PRESENTS THE WORLD SERIES OF POKER 1981. Opposite was an equally large blackboard, listing across the top the side games being played that day while the official tournament was in progress; 'Hold 'Em, No Limit - 5, 10,25,' 'Hold 'Em, No Limit - 25, 25, 50,' '7 STUD50, 100,' '7 STUD - 200,400.' Under each set of figures was a column of names and initials. The larger the numbers, the shorter the column beneath.

The game just inside the rail seemed to have been going on all night. The players were gray-faced and unshaven. They shifted about uncomfortably in their seats, yawned, scratched vaguely at their grubby shirts, lit one cigarette from the stub of another. They looked, most of them, like the uneasy sleepers on the benches in railway stations, sitting there because they could not raise the price of a hotel room. Only the dealer seemed dressed for the occasion: he wore a gleaming white shirt and a narrow black bow tie with two long tails, Western style, inscribed with the word Horseshoe. He checked the bets in front of the three players who remained in the pot, and raked those chips into the pile of chips at the center of the table; then he discarded the top card of the deck he held, and turned over a communal card, to join four already exposed in front of him. A cowboy to his left tapped twice on the table with his forefinger. To the cowboy's left, an elderly man in a bulging T-shirt stared meditatively at the exposed cards, took two black chips from the stack in front of him, and tossed them toward the center. He seemed utterly uninterested, as if the matter were somehow beneath his attention. 'Two dollars,' said the dealer, in a bored voice. The next player, a nervous young man with a Zapata mustache, cupped his hands around two cards face down in front of him, squeezed up their corners, and flicked them toward the dealer, elegantly, like a fop making a conversational point. Only the cowboy was left. He tilted his Stetson back an inch and stared at the elderly man, unblinking, for a full minute. While he stared, he juggled a pile of black chips up and down on the baize in front of him - up and down, in and out, like a yo-yo on a string. His fingers were agile and surprisingly long. Then his hand stopped abruptly, he lifted seven chips off the pile without seeming to count them, and he pushed them into the center. 'Raise it up a nickel,' he said. The fat elderly man crossed his arms on his chest, sank his chin toward them, and considered the cowboy. There was a long pause. In the same bored voice, the dealer said, 'Five dollars to you.'

A nickel? Five dollars? This was my first morning in Las Vegas, so I leaned forward to see the markings on the black chips. In the middle of each was a white disc decorated with the casino's symbol, around which was printed 'Horseshoe Club, Las Vegas, Nev.' Inside the horseshoe was a portrait of the owner, Benny Binion, in a cowboy hat, smiling encouragingly over his signature. Below that was the figure '$100.' So now I knew. Later, I was told that serious gamblers always leave off the zeros when they announce bets. Perhaps it is a way of showing their indifference. The bigger the bet, the more zeros omitted. In gambling parlance, a nickel is $500, a dime is $1000, a big dime is $10,000. 'It makes it simpler,' I was told. It also makes it more unreal.

Unreal. Over in the back corner of the enclosure, as far from the spectators as they could decently manage, another group of men was settling down to a new game. Their clothes were pressed, their hair was brushed, and they moved in an aura of aftershave and talcum powder. I recognized some of the faces from newspaper photographs and from pictures in Doyle Brunson's book Super/System, a large treatise on advanced poker techniques, strictly for postgraduates. I had studied the book like a Biblical scholar before I left London, but now I found, to my irritation, that I could remember the faces more vividly than I could remember the advice and the card analysis. Brunson himself was at the table, and Bobby Baldwin and Puggy Pearson, all of them winners, in their turn, of the World Series Poker Championship, and there were several others, some of whose faces I vaguely recognized but whose names I could not place. The big league was settling down to a morning's entertainment. The men chatted while they nonchalantly unloaded their racks of chips and arranged them at their places at the table: massed towers of black, a couple of towers of gray five-hundred dollar chips, and then, as an afterthought, a lower bastion of green twenty-five-dollar chips. Each player seemed to have his own architectural plan in mind, but the final effect was of so many grim desert fortresses. Then they fumbled around in their trouser pockets and pulled out packets of money, which they set between the chips and the raised leather edge of the table, like the garrison that the fortifications were protecting. The packets were of hundred dollar bills, as freshly laundered as the players, and each was belted with a paper band on which was printed '5000 DOLLARS.' It was a quarter past nine on a weekday morning, and the boys were settling down for a quiet game of cards.

_ocr_0003_001.jpg)