MAX BEERBOHM (18721956) was born in London and studied at Oxford. He published his first collection of essays, The Works of Max Beerbohm, in 1896 and soon developed a reputation as a brilliant caricaturist and critic. He was married to the American actress Florence Kahn and lived in Rapallo, Italy, for most of his later life. In addition to The Prince of Minor Writers, NYRB Classics publishes Beerbohms Seven Men, a short-story collection.

PHILLIP LOPATE is the author of the essay collections Against Joie de Vivre, Bachelorhood, Being with Children, Portrait of My Body, and Totally, Tenderly, Tragically; and of the novels The Rug Merchant and Confessions of a Summer. His most recent books are Portrait Inside My Head and To Show and to Tell.

THE PRINCE OF MINOR WRITERS

The Selected Essays of Max Beerbohm

Edited and with an Introduction by

PHILLIP LOPATE

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

Copyright 2015 by NYREV, Inc.

Introduction copyright 2015 by Phillip Lopate

All rights reserved.

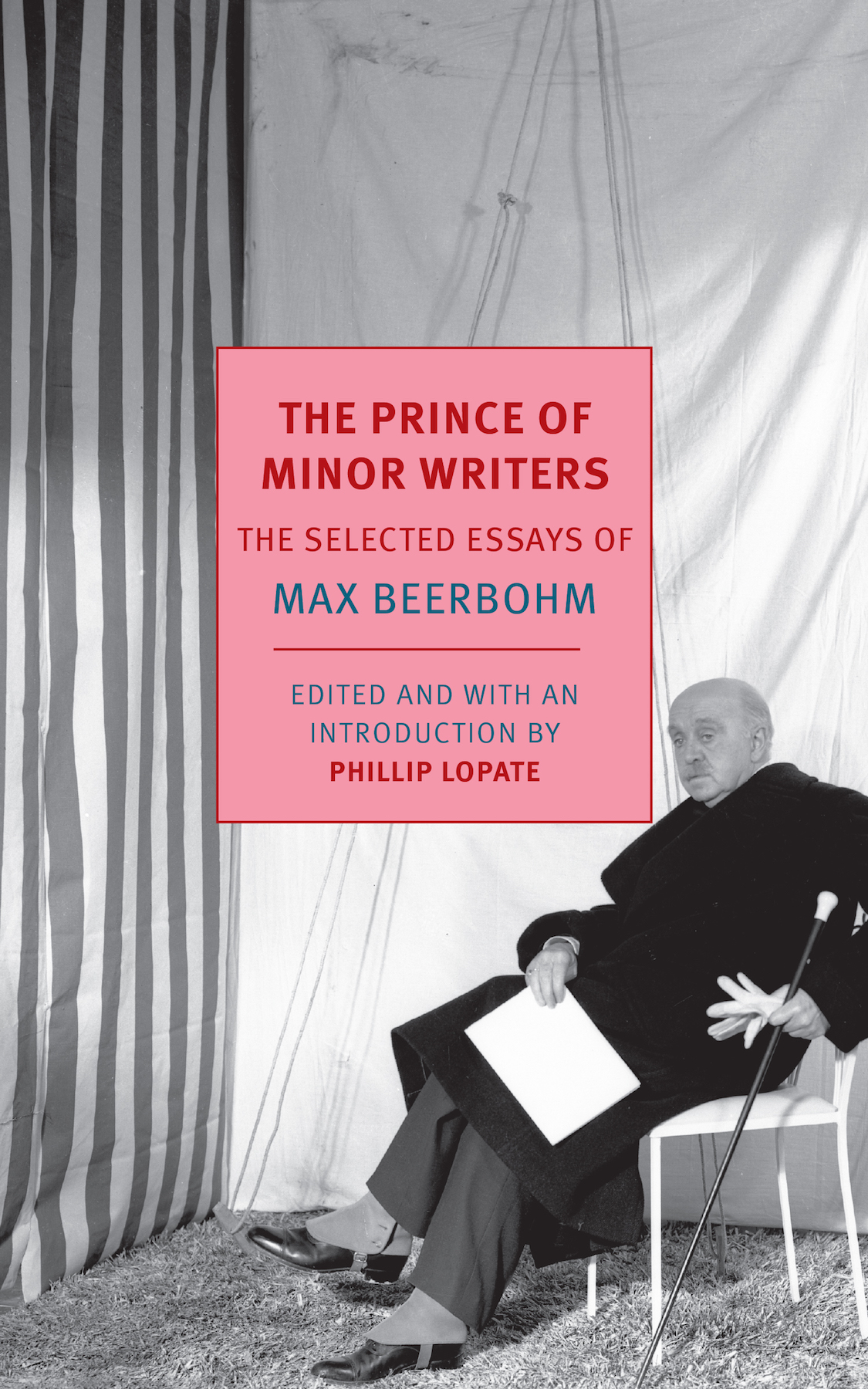

Cover photograph: Cecil Beaton, Sir Max Beerbohm, 1937; courtesy of the Cecil Beaton Studio Archive at Sothebys

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Beerbohm, Max, Sir, 18721956. [Essays. Selections]

The prince of minor writers : the selected essays of Max Beerbohm / by Max Beerbohm ; edited and with an introduction by Phillip Lopate.

1 online resource. (New York Review Books Classics) ISBN 978-1-59017-829-4 () ISBN 978-1-59017-828-7 (paperback)

I. Lopate, Phillip, 1943 editor. II. Title.

PR6003.E4 824'.912dc23

2014044254

ISBN 978-1-59017-829-4

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to: Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014.

CONTENTS

from And Even Now

from The Works of Max Beerbohm

from More

from Herbert Beerbohm Tree

from Yet Again

from Around Theatres

from A Variety of Things

from Mainly on the Air

INTRODUCTION

Max Beerbohm has always been a minority taste. There are only fifteen hundred readers in England and one thousand in America who understand what I am about, he estimated. This did not dismay him. On the verge of being forgotten, he always seems to have the good fortune of being rediscovered and championed by those with a demanding taste for invigorating prose. One such enthusiast, the critic F. W. Dupee, wrote:

Rereading Beerbohm one gets caught up in the intricate singularity of his mind, all of a piece yet full of surprises .... That his drawings and parodies should survive is no cause for wonder. One look at them, or into them, and his old reputation is immediately re-established: that whim of iron, that cleverness amounting to genius. What is odd is that his stories and essays should turn out to be equally durable.

Beerbohm himself claimed, What I really am is an essayist, and, to the degree that one values essays, one is apt to consider him not only durable but indispensable.

In her 1922 piece, The Modern Essay, Virginia Woolf singled out Beerbohm as an exemplary practitioner, while also nailing the paradox of his art. Calling him without doubt the prince of his profession, she went on:

What Mr. Beerbohm gave was, of course, himself. This presence, which has haunted the essay fitfully from the time of Montaigne, has been in exile since the death of Charles Lamb. Matthew Arnold was never to his readers Matt, nor Walter Pater affectionately abbreviated in a thousand homes to Wat. They gave us much, but that they did not give. Thus, some time in the nineties, it must have surprised readers accustomed to exhortation, information, and denunciation to find themselves familiarly addressed by a voice which seemed to belong to a man no larger than themselves. He was affected by private joys and sorrows, and had no gospel to preach and no learning to impart. He was himself simply and directly, and himself he has remained. Once again, we have an essayist capable of using the essayists most proper but most dangerous and delicate tool. He has brought personality into literature, not unconsciously and impurely, but so consciously and purely that we do not know whether there is any relation between Max the essayist and Mr. Beerbohm the man. We only know that the spirit of personality permeates every word he writes. The triumph is the triumph of style. For it is only by knowing how to write that you can make use in literature of your self; that self which, while it is essential to literature, is also its most dangerous antagonist. Never to be yourself and yet alwaysthat is the problem.

Today, when the memoir and the personal essay stand (rightly or wrongly) accused of narcissism and promiscuous sharing of information better left private, it becomes all the more necessary to ponder how Beerbohm performed the delicate operation of displaying so much personality without lapsing into sticky confession.

His readers learned everything about his temperament, how he was likely to respond in any given situationrigorously self-analytical, he was onto all his idiosyncrasies, tics, and flawsbut next to nothing about his parents, relatives, financial struggles, premarital amours, or wife. Some of that reticence regarding women had to do with his gentlemanly code: He drew almost no caricatures of women either. Aware that he shied away from autobiographical details, he wrote in sly disclaimer, personally I admire the plungingly intimate kind of essayist very much indeed, but I never was of that kind, and its too late to begin now. The fact is, he could never make himself out to be the rugged hero of his tale; what interested him more was tracking the odd turns in his consciousness.

Beerbohm, born in 1872 to a middle-class mercantile family, came to precocious prominence in the 1890s, while still an undergraduate at Oxford, when he was taken up by the artists and writers associated with The Yellow Book. This group of self-styled Decadents, which included Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde, made a cult of Beauty and assumed the need for artifice and masks. Socially he fit in, being a good listener with wit to spare and a tolerance for eccentricity, though Wilde was disconcerted by Beerbohms imperturbable manner, and asked a mutual friend, When you are alone with him, does he take off his face and reveal his mask? Beerbohm would remain loyal to the Decadents belief that beauty was the supreme goal of art, and would dedicate himself to perfecting a literary persona. But a firm grounding in common sense prevented him from swallowing the Decadents desire to shock, and he considered Wildes florid, over-the-top presentation of self a bit ridiculous.

Only the insane take themselves quite seriously, he said. Beerbohms antennae for vanity, grandiosity, and self-delusion governed him from the start. In his initial essays on dandies and rouge, his light ironic touch was so deft that he seemed to be simultaneously defending and mocking the pretensions of the artificial, as when he complimented the dandy Beau Brummell for his singular dedication to the art of dress:

And really, outside his art, Mr. Brummell had a personality of almost Balzacian insignificance. There have been dandies, like DOrsay, who were nearly painters; painters, like Mr. Whistler, who wished to be dandies; dandies, like Disraeli, who afterwards followed some less arduous calling. I fancy Mr. Brummell was a dandy, nothing but a dandy, from his cradle to that fearful day when he lost his figure and had to flee the country ....