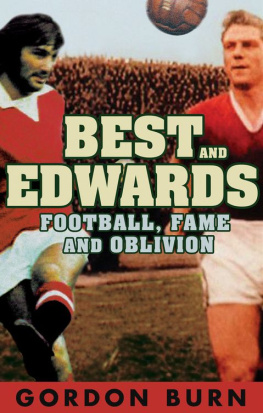

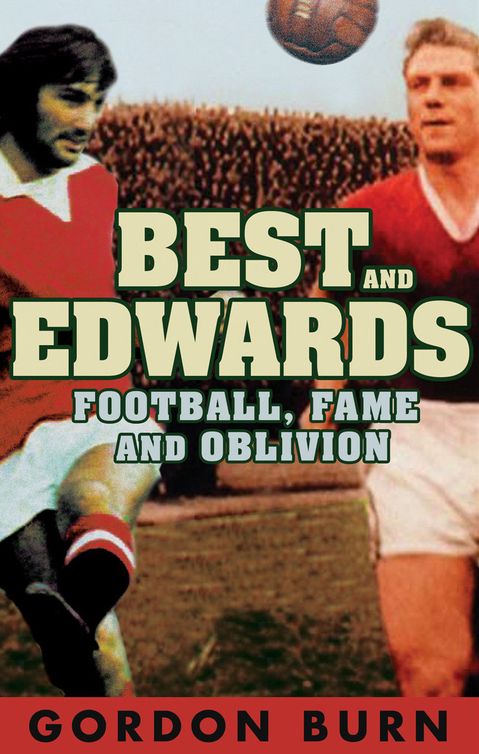

Burn - Best and Edwards

Here you can read online Burn - Best and Edwards full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Faber and Faber, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Best and Edwards

- Author:

- Publisher:Faber and Faber

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Best and Edwards: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Best and Edwards" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Burn: author's other books

Who wrote Best and Edwards? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Best and Edwards — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Best and Edwards" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

BEST AND EDWARDS

The Morrissey of English prose Far more than just a football book, this is one of the years best reads. Chris Bray, Word

Superb Burn reaches back into the myth of George Best and presents perhaps the most affecting portrayal of the legend there has been An elegiac, handsome contemplation . Alan Pattullo, Scotsman

Hugh McIlvanney has written wonderfully well on Best, but Burn is even better. He has the novelists turn of phrase, the novelists eye for the telling detail. His erudition is tremendous, but he wears it lightly Burns book is immaculately written, inspiring, sad and elegiac. Andrew Baker, Daily Telegraph

Gordon Burn, a superb journalist and Whitbread-garlanded novelist, concentrates here on more important matters: the lives of Edwards, tragically curtailed by injuries received in the Munich air crash of 1958 when he was 21 and already well into a dazzling career, and of Best, who dazzled and stumbled and kept stumbling until he died at 59. Patrick Barclay, Sunday Telegraph

A very sharp and timely incision into the bloated belly of metropolitan England. In what is in effect a cultural history of Manchester United, Burn tracks the changes through the very different lives of Duncan Edwards and George Best. Robert Colls, Prospect

Burn excels as a chronicler of real lives, a skill evident in this study of two very different Manchester United players: Duncan Edwards, cut down at Munich when set to dominate the game, and George Best, who lived out a long public death. The contrast allows Burn to trace a familiar pop cultural arc one apt to forget substantial achievement in favour of soiled celebrity. Observer Sport Monthly

It is a great achievement to have written a radically different book about Best, in particular just when it seemed there could not possibly be anything left to say. The detail is riveting . The book is rich in themes. It is remarkably resonant. Kevin McCarra

for

Carol Gorner,

and in memory of my father

The worlds champion worrier. It is a face on which worry more accurately worritability, the under-colour of worry seems to have been permanently imprinted. It looks like a face incapable of lighting up with joy; a face from which joy, or even the open and unselfconscious expression of pleasure, has been forever extinguished.

Even when England won the World Cup in 1966, bringing to a climax a summer month brimming over with a very un-English sense of carnival and expansiveness, Bobby Charlton brought a mask of tears to show the presentation party at the Royal Box. His first question to his brother Jack, on the pitch sharing the victory with him, had been a ball-aching, worritable one: What is there to win now?

Less than a month later, hailed, alongside Jack, as a returning hero in his home town of Ashington, Bobby arrived late and then spent the processional half-mile from the colliery terrace where he had grown up to the Town Hall looking, according to contemporary observers, anxious and on edge. While Jack perched on the back of the rear seat of the open car, taking the cheers of the crowd, waving to familiar faces from his childhood that he recognized, sending up the fact that he was riding past them as a winner in a Roller, Bobby remained seated and sombre. Even his mother, the ever-exuberant Cissie Charlton, remarked afterwards that their Bobby had looked peaky and distinctly uncomfortable.

Although in north-east legend he is always fused in an unusually close relationship with his mother, a daughter of the goalkeeper Tanner Milburn and cousin of the great Jackie and a long line of footballing Milburns, Bobby actually took after his father temperamentally. Bob senior liked his pigeons and his allotment and his own slow company and, typically, had worked his usual shift at the Linton pit in Ashington instead of watching Bobby play what everybody said was the match of his life in the semi-final of the World Cup against Portugal. He felt well shot of the hoo-ha and the blether.

In 1968, ten years after Munich, when Manchester United finally won the European Cup by beating Benfica of Lisbon at Wembley, Bobby was a no-show at the after-match party. Crowds in their thousands milled around the Russell Hotel in Kings Cross that night; the celebrations inside went on until dawn. George Best, who scored the first of Uniteds winning goals in extra time (Charlton got the killer goal, the third after the restart), would later claim to have no memory of anything that happened after the team left Wembley; as was to be the case so often in the coming years, recall was obliterated by the alcohol. I dont remember going to the official dinner, Best later said, though Im told I was there.

Also invited as guests of the club were the families of the players who died at Munich. But, when it came to it, Bobby, perhaps not surprisingly, couldnt face them. He sent his wife Norma down to apologize for his absence. It has all been a bit too much for Bobby, she explained. He is just too tired physically and emotionally to face up to all this. He couldnt take it, with complete strangers coming up and slapping him on the back and telling him what a wonderful night it is Hes remembering the lads who cant be here tonight.

Once in his room, Charlton had felt faint. He was drained. It had been eleven years since Matt Busby flying in the face of official and unofficial opposition from the English football authorities, who still, at mid-century, regarded continental teams as wogs and dagoes (to quote League Secretary, Alan Hardaker) had embarked on his renegade European adventure . Eight of Charltons fastest friends, among them Eddie Colman, Duncan Edwards and Billy Whelan, had met their deaths at Munich. The average age of the players who died in the disaster was twenty-one. Now he had eventually arrived at the destination they had set out for together. Soon, in recognition of the Lazarus act he had performed both professionally and personally, heroically hauling himself back from the appalling injuries he sustained in the crash, the Boss would be honoured with a knighthood.

Every time Charlton tried to ease himself off the bed in the room overlooking the heaving crowd and Russell Square, his legs buckled. The surge sensation, the leap of people already standing, that bolt of noise and joy when the ball went in. He felt old prematurely, with feeble limbs and double vision and dizzy spells. Every time he tried to make it to the bedroom door, he fainted. When he swung his legs off the bed, his legs couldnt take the weight of him. And tomorrow would bring only more of the same: the consuming guilt of being a survivor when his friends had perished; the trial of carrying the Cup home in glory to Old Trafford, parading it in convoy past the waving and cheering, screaming-themselves-hoarse Red thousands of the fanatic faithful; glad-handing the silverware, holding the big, bowl-sided trophy up to collect their reflection when, if any of them were doing it, it really should have been Duncan.

We passed them / All poised irresolutely, watching us go / As if out on the end of an event / Waving goodbye / To something that survived it. Philip Larkins lines from The Whitsun Weddings, written in 1958, the year of Munich, contain all the melancholy which, in the ensuing half-century, the crestfallen, dutiful figure of Bobby Charlton would come to embody.

So synonymous has he become with sobriety and black-braided ceremonial the scrubbed-up, bow-headed figure in the unexceptional suit acting as a representative of his club, his sport or his country, not infrequently appearing to be teetering on the edge of one of his dizzy spells that the other Bobby Charlton, the player that many who saw him play at his peak in the sixties thought comprised the athletic ideal, quick and full of intelligence, his massive goal-scoring power erupting on the run suddenly, out of an inborn, flowing elegance He used to delight people, his old grammar-school headmaster once said

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Best and Edwards»

Look at similar books to Best and Edwards. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Best and Edwards and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.