ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thank you to my entire family for your endless support and guidance, and tomy friend, Joe, for joining me on this wild adventure.

Other Acknowledgments

Animal Allies, Lorna Aho , Cloquet Friends of Animals, Nancy Altena ,AVRAL, Brian Batista, Carol Bement , Mani Berti , Terry Blair, Richard Burgess, Paige Calhoun, JeffCerise, Garland Clarke, Bill Cowardin, Kati Cowardin, Lewis and Eustis Cowardin,Ted Cowardin, Carol Crocker, Darren Danielson, Jen Drier, Hannah Rey Dunda , India Erb , Fran Fields, RobbieFitzgerald, Brandt Garrison, Kim Gentry, Emily Haavik ,Lisa Hansen, Ryan Hanson, Lee Harrington, William and Dee Hartley, JohnHatcher, Kim Hyatt, Lisa Johnson, Chris Julin , Glenn Kellahan , Brenda Knutson, Peter Knutson, Richard Koerner , Rachel Kraft, Brenda Lafontaine, Dayna Landgrebe , Ingrid Law, Dr.Leonard, The Leonard Family, Pam Leonard, Rachel Leonard, Paul Lundgren, Greg Mahle , Adam Meyer, Bonnie Miller, Tim Miller, Rod Moody,Sandra Nathan, Don Ness, Northlands Newscenter , Karin Newstrom Photography, Jennifer Dial Nolan, ErickaOlin, Matthew Olin, Joe Olivieri , Joseph Olivieri , Mario Olivieri , RhondaParker, UMD Beta Lambda PSI, Leavellwood Ranch,Austin Dog Rescue, Carl Sauer, UMD Statesman, Kaci Stokley , Scott Stone, Sonya Smith, Cynthia Sweet, BobbieTaylor, Emily Thompson, Zach Vavricka , Tina Watson,WDIO-TV, Pat Webb, Wheels4Paws, Javalyn Wilson,Catherine Winter, Dena Yjana ,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

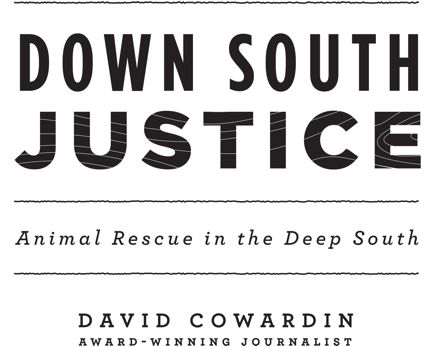

INTRODUCTION

WHEN I RESCUED LENNY LOU, a lab/pit mix from Alabama, I hadno idea what dog ownership would be like. I also didnt know Lenny had skinmites that would require me to dip her in acid baths, which ultimately led toLennys fear of water as a puppy.

I live in Duluth, Minnesota, andspend the majority of my free time near water: fly fishing and kayaking thetributaries of Lake Superior and paddling the Boundary Waters Canoe Area, afederally protected wilderness area in the Superior National Forest. I lovewater and now owned a dog that wanted nothing to do with it.

When Lenny was about a year old,I took her to the Lester River, where my fianc, Dena, and I would jump fromhigh cliffs into a deep pocket of water and bathe in the cold current. WhileDena was playing with Lenny near the river, I climbed to the top of a cliff totake my first jump.

Lenny! I called down to mywater-wary pup.

Lenny cocked her head at a90-degree angle, curious as to why I was perched on a cliff above the river.

Then, I jumped, and on my waydown, could see Lenny leap into the water, paddling awkwardly toward the middleof the river. When I emerged from my plunge, Lenny was circling me and pawingat my back, trying to rescue the man who rescued her.

Since then, Lenny has joined meon multiple trips to the Boundary Waters and has learned to jump from docks toretrieve sticks. Shes also sat in my kayak as I paddled through rapids andover ledges. She still hates taking baths, but were working on that.

I willnever forget the day Lenny overcame her fear of water, because it was the firsttime I understood that dog ownership, isnt ownership at all. Itscompanionship. Its family.

I rescued Lenny after producing the documentary, Roots ofRescue, which unveils the plight of animal rescuers in Alabama.

This book is an uncensored,intimate telling of those stories, recalling the journey of twophotojournalists embedded in the American South, following a network of animalrescuers. Some carried badges and investigated under official capacity; otherswere vigilantes, taking the law into their own hands.

Justice, to the men and women wefollowed, had nothing to do with the law. Their form of justice was a differentbrand, a down south justice.

PARTONE

I SHOTRIGHT AT THE BASTARDS

THERE IS A GUN ON ALMOST EVERY SIDE TABLE AND NIGHTSTAND inher house and 40 rescue dogs howling from runs and kennels in her backyard.

Bonnie Miller is making a laststand in rural Greene County, Alabama. The crazy lady on the hill is pushing60 and still investigating animal cruelty against her better judgment becausesomebodys gotta do it.

Armed witha revolver, badge, and store-bought CSI hat, Bonnie noses her SUV down dirtroads in Alabamas rural ghettos, looking for signs of dog fighting. She alwaysfinds something.

Joe Olivieri and I were sitting inBonnies breezeway on fold-out lawn chairs waiting forthe humidity to break. A gibbous moon hung in the night sky, crickets chirped achorus with howling dogs, and mosquitoes emerged from the woods. Everything washot and sticky. Nothing about the scene was spectacular. Nothing was special.

I slouched back in my chair andlifted my arms to air out my sweaty armpits. It had been days since my lastshower. A soap container hung mockingly from the rearview mirror of the 25-footRV we borrowed from Joes grandfather. It had no water or air conditioning, andit smelled like old marijuana and sultry ballsack .But, it was home.

I could hear Bonnie flip on ablender inside the house, mixing us drinks.

Joe gave me a look that hesgiven me before, one that said how thefuck did we end up here?

Then the screen door swung openand Bonnie walked out with a sweating pitcher of pina colada. She poured us drinks in plastic cups and we debriefed on our first dayin the field with her.

It was pathetic. Heaps ofgarbage burned in yards everywhere we went. Dogs lay dead in ditches withrotting gun shot wounds maggots occupying their insides. It was a real shithole, a third world country hiding in the swamps of our nation. Overlooked andforgotten.

We followed Bonnie as she kickedup dust in neighborhoods where drug dealing and dog fighting were ubiquitous.Bonnie normally refused interviews with journalists but figured, what thehell. A couple of college grads with cameras certainly cant make thesituation any worse, and at least this way she would have some company andbackup in the field.

Bonnie refilled her cup to takethe edge off and reached down to pet a jumpy rescue dog she adopted. Then sherepeated something she told us multiple times throughout the day: The peoplein this county, they just dont give a damn, she said. Not a damn.

Shes right. Nobody gives adamn. Not the people in rural ghettos, not the law enforcement, and not thepeople insulated in nearby cities. Heck, Bonnie barely gives a damn anymore.Shes been abandoned and left to fight a war on her own.

According to state law, everycounty in Alabama is supposed to have an animal shelter and animal controlofficer. Greene County, however, has Bonnie and her husband, Tim. Theirproperty stands as the de facto shelter, with Bonnie the officer and Tim thefinancer. The operation has absorbed their retirement fund and at times,threatened their marriage.

You can see it in Bonnies eyesas the sun goes down and her transitional lenses unveil more of her emotion:agony, stubbornness, and fearful pride. Shes the embodiment of the dogs sherescues. But nobody is coming to rescue her because nobody gives a damn.