For Lu, with whom I like to eat

Contents

If you are going to follow links, please bookmark your page before linking.

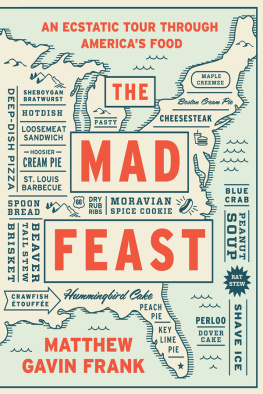

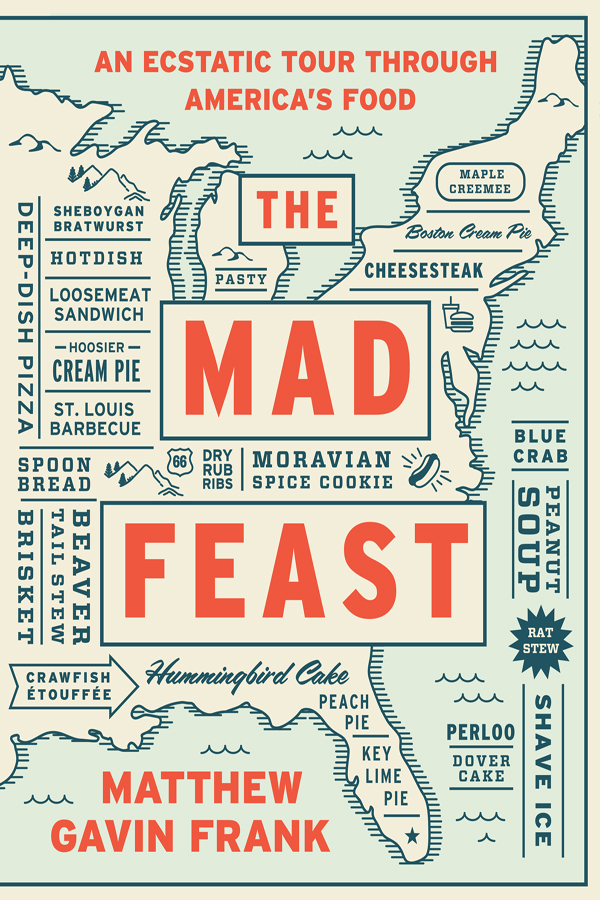

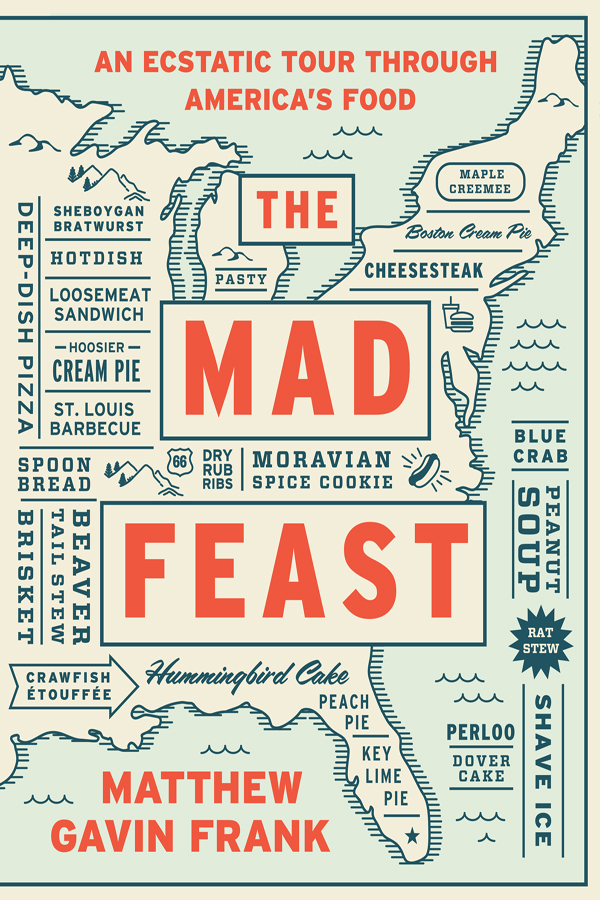

THE MAD FEAST is intended to be a spastic, lyrical anti-cookbook cookbook of sorts that also may be a fun and digressive revisionist take on U.S. history. The choices of dishes herein reflect the ways in which these dishes seem leashedin ways both real and impliedto their states history or geography, how issues of temperature and texture, density and depth, sweetness and spice span the food and the place. The book is ordered to reflect a diverse journey around the U.S., and therefore region-hops. After we live in one region for a while, the subsequent section is meant to offer a little vacation, in a different landscape and culture.

Each essay begins with this line of questioning: What does the state at hand mean? What does a typical foodstuff associated with said state mean? What does Alabama mean and what does hummingbird cake mean when wedged into the context of that states history? How do state and history and foodstuff relate? What ancillary subjects will I have to engage in order to stalk both food and state toward the blurry answers to these questions?

After spending twenty years working in the restaurant industry (my first job was as a dishwasher in a fast-food chicken shack on the outskirts of ChicagoI was eleven years old), and the years thereafter often thinking and reading about all things edible and imbibable, I became interested in exploring a new kind of food writing. So much of our food writing seems interested in engaging food as easily delicious, as a shortcut to meditations on celebration, ceremony, memory, and/or family. This is certainly one admirable, and familiar, way to engage food, of course. As opposed to treading this ground, and to seeking out the scrumptious, I grew more interested in exploring notions of the un-scrumptious. During the writing process, these essays grew more and more preoccupied with whether an engagement of food can wrangle with the un-scrumptious while still retaining the element of sensuality. As a result, its my hope that The Mad Feast embodies the forms of food writing and the cookbook while interrogating the parameters and roles of each.

Throughout the book, the character of Uncle (and sometimes Aunt, Mother, Father) makes a dominant appearance. A fairly obvious admission: the uncle is not always entirely my uncle, and the aunt is not always entirely my aunt. As I was writing these essays, I visited and/or interviewed a bunch of folks in the state at hand. Invariably, certain personal connections of mine wouldnt be able to answer some of the focused questions I had, so they would direct me to friends of friends of friends, and eventually, someone would say, Oh, yeah! My uncles a lobsterman who lost a finger! Or, Oh, yeah! My uncle used to work in a bowling ball factory and is now getting through his forced retirement by obsessing on racehorse injuries! I made phone calls and sent emails and rented a string of cars and drove a wealth of miles until I found that someone who had worked at a bowling ball factory. In other cases, the guy who worked at the bowling ball factory serendipitously presented himself and redirected the essay in progress. And in other cases, I was lucky enough to talk to the aunts and uncles themselves, and invariably, I looked for connections between their livesbe it a manner of speech or another aspect of their personalities, historiesand the lives of my own uncles, aunts. And I looked for odd connections between other nephews across the country and me. Looking for communion. So the uncles and aunts throughout are composite charactersone part my uncle, many parts other peoples uncles; are Uncle and Aunt, collective archetypes embedded within other archetypes, like America, and Food.

That said: nothing in the book is entirely fabricated. The protagonist in each essay represents a version of me and my experience, embedded within variousand realregional histories and landscapes. The occurrences of the mothers and fathers in the book are based on aspects of my actual parents and our relationships. When my wife shows up, the character is based on my actual wife. Nonfiction is a funny genre. Its the only genre defined by what its not. Its not fiction, but what is it then? Ive applied the term essays to these pieces instead, as they are (as essays are, by definition) a series of attempts, as opposed to presumptions of certainty. These pieces grapple toward a larger, nebulous truth that might exist beyond or in spite of me, but for which, in order to approach it, to draw a chalk outline around it, I needed to engage various aspects of myselfvia various lensesas tools.

Though I often resist being this confessional: all of the events herein are rendered as the products of my lived experiences in conversation with researcharchival, observational, interview-based, etc. (the lenses)with the goal of uncovering a larger, if implicit, statement about the intersection of who we are, how we live, and how/why we eat. Unless I overtly signal to the contrary, or in obvious cases (the ever-reincarnating Arkansas beaver, for instance), all of the events in this book happened in the lives of real people, or they happened to me. Thats me living out of the garage in Vermont. Thats me in the Illinois slaughterhouse. Thats me and my wife in New Mexico, Mississippi

HERE, OUR CITRUS IS DWARF , the rind thinner, the acid mapping our tongues. Here, we name our citrus after our island chains, which weve named after the tiny metal code-crackers that unlock our doors. Here, our code-crackers come at us like our limes: with teeth. This is chemistry, concentration, this is a boiling down to, and a boiling down to something that will burn us, eat away at our mouths. Here, the more dessert we eat, the more we slur our speech. Here, the ear is the code-cracker, deciphering with its nodes and whirls the complaints of a lime-battered tongue.

This is lime as a halogen bulb, as something we have to squint against to see, swallow. In condensing the fruit like this, Florida offers us the kind of dare we can take only beneath an armor of sugar. Here, in this kind of heat, my uncle collects a basketful of bougainvillea flowers for his new girlfriend. They are red, or they are pink, or they are white, and they have grown between thorns and are otherwise known as the paper flower . These are the flowers we can record our names, and the names of our favorite desserts, on.

Here, expressions of love are condensed until too thick, until too thick to run from the fat can into whose lid Uncle has cut a triangle with a can opener with another fucking palm tree on its handle. Just east of here, tourists swim among the sea lice off of Fort Zachary Taylor Beach, wonder if the resulting itch in their crotches is more sour or sweet.

In Key Lime Pie, we temper the acid with sweetened condensed milk. This does little to keep the key lime from spoiling faster than other citrus. Just east of here, no one wonders why we name our beaches after the last president to own slaves while in office. Regardless, the hog snapper swim beneath us with the yellowtail and the grouper, never once considering the panic in our legs, the panic necessary to keep from sinking, which here, is just another kind of spoilage.

Next page