THE MANY DEATHS OF MARY DOBIE

MURDER, POLITICS AND REVENGE IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW ZEALAND

DAVID HASTINGS

Contents

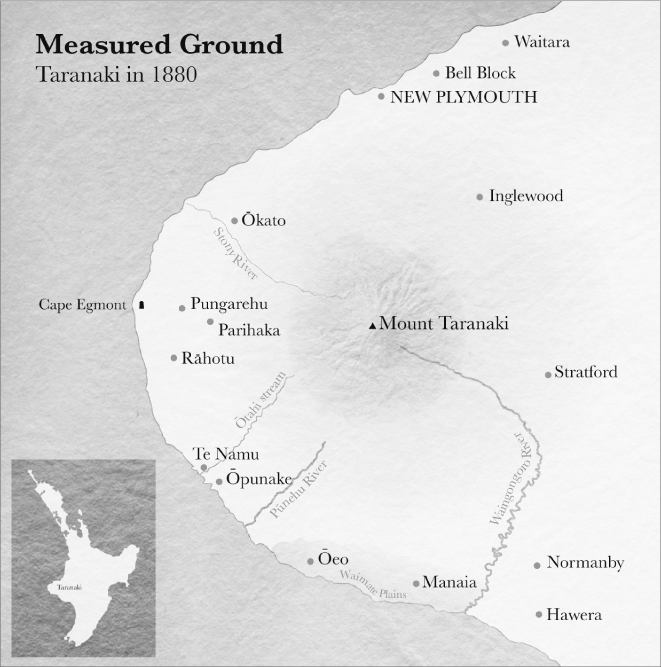

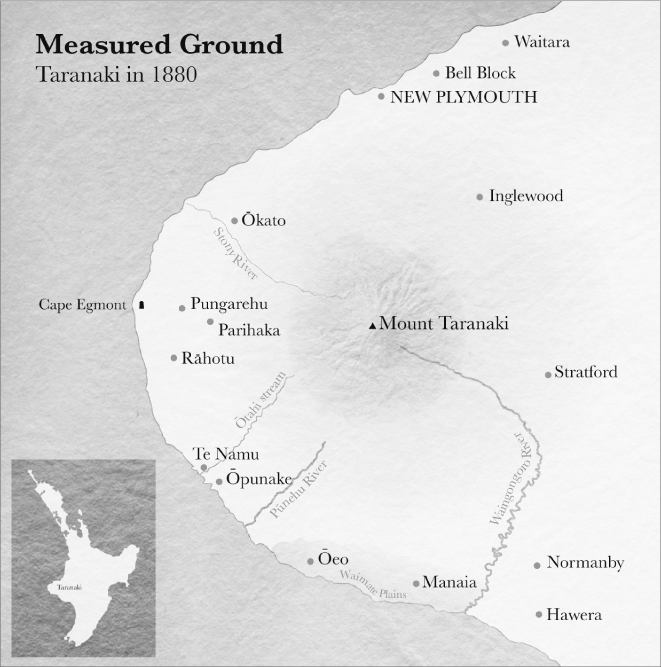

Measured ground: Lands in Taranaki were confiscated after the wars of the early 1860s. By the late 1870s the surveyors were moving in to prepare the land south of the Stony River for sale. MICAELA LOWIS

TOMB WITH NO EPITAPH

After lunch on the last day of her life Mary Dobie went for a walk along the road leading north from the small settlement of punake on the Taranaki coast. It was late spring in 1880 and she was staying at the well-fortified redoubt in the town with her sister Bertha, the wife of an Armed Constabulary officer. Mary, who was an accomplished artist, stopped briefly to buy a pencil, apparently intending to do some sketching near Te Namu P about 2 kilometres away. She was more than just a dabbler; examples of her work from New Zealand and the Pacific Islands appeared in the London Graphic magazine, renowned for the quality of its illustrations. Mary was making the most of these natural splendours because she was about to return to England with her mother after three years living and travelling in New Zealand and the South Pacific.

The road she walked that day was as rich in history as the scenery was beautiful. One of the best tales told on the coast was about a local chief, Wiremu Kingi Mataktea, who had won fame at Te Namu P in 1833 when he led 150 Taranaki defenders as they fought off an attack by a superior force of 800 from the Waikato during the musket wars.

Despite the beauty of the landscape there were signs of desolation everywhere. As Mary walked along the road she passed the ruins of an old flax mill which had thrived briefly ten years before. And the dwellings at Matakteas settlement were now deserted, a reminder that she was on contested ground claimed by the first inhabitants and the new settlers.

The coast was frequently stormy but on the last day of Marys life there was a gentle southwesterly breeze, with mostly clear skies and a flat sea. She gathered a bunch of flowers as she went and the last people to see her alive, other than her killer, The dogs belonged to her brother-in-law, Major Forster Goring, who was stationed in Taranaki on account of tensions over the disputed land. The great walls of the redoubt perched, like Te Namu P, on a clifftop overlooking a bay testified to fears that those tensions might explode into deadly violence. But Mary had never allowed conventions or stuffy Victorian customs to inhibit her and she wasnt about to be corralled behind high, defensive walls on account of some fear that might be more imagined than real. In the few weeks of her visit, she had freely walked around the countryside sketching and chatting to people from all walks of life: Mori and Pkeh, soldiers and civilians.

Her plan on that springtime day was to be back at the redoubt in time for a game of tennis with Bertha. But the sisters never did play. The appointed time came and went with no sign of Mary. At first Bertha was not too worried. She thought her sister must have lost her way in the dense flax that covered the land between the road and the sea or, perhaps, had slipped on the rocks near the beach and sprained an ankle. Three Armed Constabulary (AC) men went to look for her in the late afternoon. By the time darkness was falling and there was still no sign of Mary, the search party was expanded to include every available man. They called out to her, lit fires along the coast and, with flaming torches held high, retraced her footsteps along the road.

After a few hours one of the searchers found Marys body lying in dense flax about fifteen paces from the road near a cluster of stones. Forster, as the senior officer in the redoubt, was summoned to view the horrifying scene by torchlight.

Everyone in small-town punake heard the news that night and by the following afternoon, when the evening papers came out, the rest of New Zealand knew about it too. The tone of the coverage was set by the headlines: Dreadful murder at Opunake, said the Taranaki Herald, Shocking outrage, was how the Evening Post in Wellington put it and other papers called the murder horrible, diabolical and brutal.

As with all big, breaking news stories journalists hastened to gather and publish as much information as they could. In the rush, it was disorganised with many papers running two, three or even four versions of the story simultaneously.

Readers were confronted with a mass of information, much of it contradictory. For instance, there was no certainty about the time the body was found. Some said 9.30 p.m., others 10.30. The scene of the crime was another source of confusion. Some said the body was 100 yards from the road, others 40. The Evening Post was even more confused. It said the crime had been committed south of punake when every other paper except the Auckland Star reported correctly that Te Namu was to the north. And how old was Mary? One paper said 22 and another 26. Her correct age was 29; she was just a few weeks from her thirtieth birthday.

But if getting the basic facts right was a difficult task on that first day, it was as nothing compared to the deeper questions: who had committed this atrocious crime and why? A number of answers were to be given in the coming days and Mary was to have many deaths in print and in the popular imagination as people struggled to explain and understand what had happened. Many Pkeh feared it was an act of political terrorism in response to the states determination to take the land of the tribes in the region. Conversely, many Mori thought it would be the cue for the state to use force against them. Rape was another motive that was reported with the certainty of fact even before the results of the post-mortem examination were known. Or was it robbery or maybe just the inexplicable act of an uncivilised savage? Then again, it might have been simply a crime of drunkenness. And who had done the deed? A gang was to blame, said one theory. Someone acting alone said another. A Pkeh was the killer, but no, maybe it was a Mori. One school of thought even blamed Mary because she had put herself in harms way by strolling unescorted along a lonely road.

Mary was buried in the AC cemetery outside the redoubt, which is the last resting place of about fourteen people from the old days. No one knows the exact number because the graves of between six and ten Irishmen who served with the AC are unmarked.information. The main one merely gives the span of her days and the names of her parents; her father had been a major in the Madras Army and her mothers name was Ellen. The secondary one says it was the non-commissioned officers and men of the AC who erected the gravestone.

It is puzzling that the men who went to such lengths to commemorate Marys life could not think of something more to say. It may be that they were simple, pragmatic people not given to expressing deep emotions or ideas and so confined themselves to the safety of specific facts and details. But soldiers frequently wrote or selected epitaphs to put on the graves of comrades who had fallen in battle. A number were to be seen at the Mission Cemetery in Tauranga when the Dobie sisters visited there in the autumn of 1879. A man greatly esteemed and deeply regretted by his comrades, read the inscription on the tomb of a soldier killed at Te Ranga in June 1864. Time like an ever rolling stream, bears all its sons away, reads another, marking the last resting place of a man who fell at the battle of Gate P in March of that same year. Yet another was distinguished for the black humour in its message to the living: As you are now, so once was I. As I am now, so you must be. Prepare for death and follow me.