Caroline Smith was born and educated in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, and has a degree in history from Lancaster University. After taking an accountancy qualification and working mainly in manufacturing, Caroline and her husband relocated to the Isle of Man.

Caroline is the author of several articles about the island. She is also involved with the local History in Action group, who aim to tell the stories of the island, including those of the Great War, through drama.

First published in Great Britain in 2014 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Caroline Smith, 2014

ISBN 978 1 78383 122 7

The right of Caroline Smith to be identified as the author of

this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted

in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including

photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in Times New Roman by Chic Graphics

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of

Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery,

Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways,

Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press,

Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When,

Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

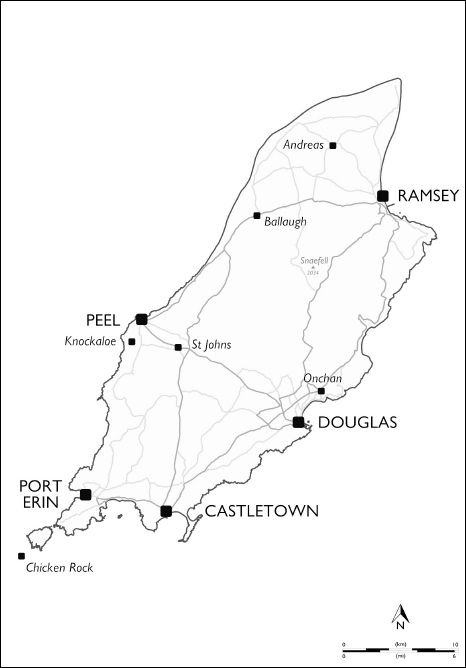

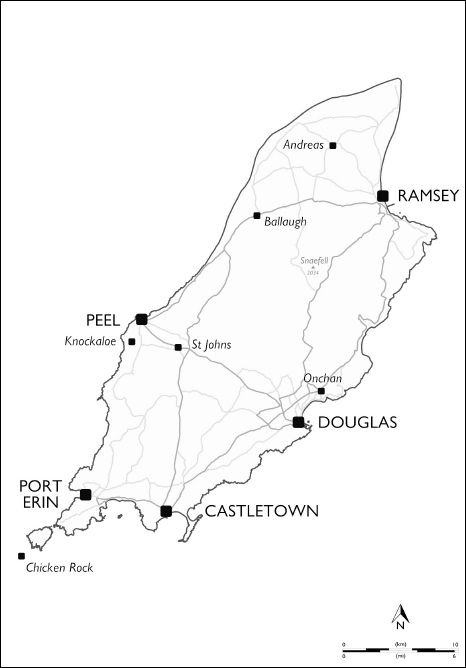

Map of Isle of Man. Courtesy of Dan Karran.

Introduction

Nestled off the coasts of Scotland and Cumbria, in the northern Irish Sea, lies the Isle of Man. This small island, only 221 square miles, is known today for the TT Races and for being a financial centre.

In 1914 the population of the island was about 50,000 and the main industry was tourism. Between Whit week and the end of September hundreds of thousands of tourists, many from Lancashire, flocked to the island for a holiday.

The season of 1914 looked as if it would be the best ever and it was in full swing when war brought that to an abrupt halt. While those dependent on the season faced an uncertain financial future, others, notably farmers, would become wealthy. This growing financial division would play its part in the increasing social tensions of war time.

Politically, the island did not have the independence that it does today. Legislation in the latter half of the nineteenth century had given the island more freedom to manage its own affairs, but the British Government and Crown appointed Governor still had much influence.

Just as in the Houses of Parliament in London, the Manx parliament has an upper and lower house. The lower house, or House of Keys, has twenty-four elected members or MHKs. The upper house, or Legislative Council, has ten members. At the time of the First World War these were appointed and the Lieutenant Governor presided over them. To pass legislation the two houses meet in a full parliament called Tynwald.

Every year on 5 July, there is an open-air ceremony at St Johns where all the Acts passed by Tynwald during the preceding year are proclaimed to the assembled crowd in both Manx Gaelic and English. The Tynwald Day ceremony, which has taken place for over a thousand years, is not only a national holiday but also the chance for the islanders to present grievances for the attention of the government.

Douglas War Memorial.

In the early years of the twentieth century there were many on the island who hoped to see British influence recede and the power of the Governor reduced. There were also calls for reform, particularly of the unaccountable Legislative Council. The British Government had already reported on reform for the island and they were receptive to the principles, however the Manx Government, under the leadership of the Governor, had been very slow to put any changes in place.

In 1902, Lord Raglan, a distinguished military man, became Governor. Unfortunately, he displayed hostility towards the Keys and, as an ultra conservative, he was often at odds with the Liberal Government in England. This recipe for conflict came to a head during the war. The failure to implement social policy in line with England and an unreformed Legislative Council where self interest ruled, were among the many grievances held against him.

When war came to the island, it gave the impetus to those who were most affected by it to demand reform, both socially and politically. By the time peace was declared the pro-reformists were seeing positive steps being taken towards their aims. The battle had been bitter and brought many divisions to the island.

Of the 50,000 population, over 8000 Manxmen served their country. This represented eighty-two per cent of the islands males of military age. Few places gave so high a percentage of their men and over a thousand of these would never return. This is the story of the people they left behind.

Note to reader all government accounts figures are in accordance with Samuel Norris.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my many thanks to the staff at the Manx Museum and iMuseum, who have been most helpful, and also to cartographer Dan Karran www.dankarran.com.

CHAPTER 1

1914

Eager for a Fight

Officially war was declared on Tuesday, 4 August 1914. However, two days before, the towns of the Isle of Man witnessed what the Peel City Guardian, a local paper, called the first omen of trouble. In full view of the patriotic crowds that had gathered, the islands Royal Naval Reservists were called up.

When the west coast city of Peel had been in its prime, this would have been a disaster. Fishing had been the main industry and, as a majority of fishermen were reservists, it would have meant its virtual paralysis. Fishing, though, had been in decline since the 1890s. With fewer men turning to it, it did not suffer as badly in 1914 as it might have done. Even so, the town still lost a large number of men who were hurried out to join various posts of duty.

Despite the impending loss of many of Peels men, the city was in a state of excitement, with just about every resident taking to the station or the quayside to give the local reservists a hearty send-off. Such was the fever that church was almost forgotten as so many wanted to shake the hands of the men departing, sing patriotic songs and cheer them on their way.