To Sefton Sandford

19252012

The crickets gone; we only hear machines.

David McCord

III

If it were not for the war,

This war

Would suit me down to the ground.

Dorothy Sayers

III

Somethings going to happen, Blue.

Australian bowler Tibby Cotter, moments before his

death in action

C ONTENTS

A few years ago I was watching my local cricket club in action when a man of about middle age, coated in designer stubble and with several bits of metal puncturing his face, clad only in voluminous army-surplus shorts, came by to chat. I should mention that the club is in Seattle, USA. After watching the game for a few minutes with an increasingly bemused expression, he asked the inevitable question: could I please explain the attraction? I made the usual not very successful attempt by an Englishman to decipher the game of cricket to an American.The man left, rocked to his core that one batsman could score as many as 20 or 30 in a single game and, I think, also muttering something about a contest that can last five days and end in a draw not immediately conforming to American-spectator standards of entertainment. It was only later, giving the matter some more thought, that I realised the answer to the question was in fact security . With one or two rare exceptions, Ive always felt completely and contentedly safe while at a cricket match: not only physically safe, but safe from the faintly nagging feeling that something, somewhere, is about to happen to my ultimate detriment. For me, its a sort of holiday from the real world. So long as Im at the back of a stand at Lords or the Oval, or sprawled under the boundary trees in Seattle, nothing can go seriously wrong.

All of which is fine as far as it goes. Perhaps one needs to be mildly paranoid about the outside world in the first place in order to find a sanctuary in cricket. It is worth mentioning only because of the very obvious contrast to the players and spectators of the game in England exactly a hundred years ago; for many of them, life could hardly have been less safe or secure as the clock wound down inexorably to the first week of August. It only adds to the poignancy of the story to see how few of them had any inkling of disaster until almost the last instant. Four out of five adults in Britain, according to one study, actually and consciously disbelieved that there would be a general war right up until the moment on the bank holiday Friday of 31 July 1914 when the Stock Exchange closed down early for the first time in its 113-year modern history. If the bankers were worried, so should we be, said Harold Wright, an opening batsman at Leicestershire. Just over a year later, Wright was mown down in the sustained and ultimately futile Allied offensive at Gallipoli. He was 31.

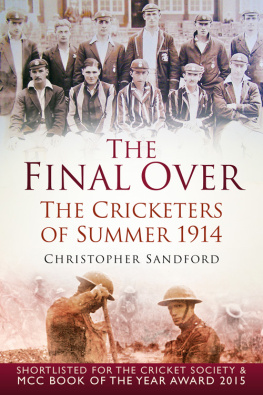

The Final Over is not a statistical, or necessarily a chronological, record of every first-class cricket match played in England that season. There are other books, notably Wisden , that do the job admirably. It does, however, take the view that cricket is a reflection of life, and that by and large cricketers reacted to the crisis in exactly the same way as everyone else, no better and no worse. The records show that they volunteered at broadly the same rate as other young men, and that they died, too, in proportion: in coldly statistical terms, roughly one in nine of those who fought did not return alive. This book follows some of those individuals and their families on and off the cricket field, and ultimately onto the bloody beaches of Gallipoli, or into the trenches of Flanders that had been churned into a sea of mud and rubble.

The Final Over attempts to shed light on the golden age of English cricket; to demonstrate what it meant to be an amateur or a professional player a hundred years ago; and to show again the arbitrary nature of war, where one man could fall and the man next to him come home and live to be 90.

And there were other casualties. The outbreak of war weighed heavily on some of the recently retired greats of cricket, many of them already struggling to cope with what Andrew Stoddart, the former England captain, called life after death. As well see, the implications for several of these men would be devastating. The notion of an industry or profession jettisoning some of its most distinguished practitioners in their early middle age may also have a certain resonance today.

Finally, this is neither a political nor a military history of the First World War. There is no shortage of published work on the subject, and a very few suggestions can be found in the bibliography at the end of the book. I should also make clear that it is not a comprehensive list of all worldwide cricketers in some way affected by the war, and no slight is intended on any name omitted. My own main interest is the narrower but hopefully timely one of showing how certain British public figures, particularly sportsmen, reacted to the events of that summer. During the two years I was writing the book, I sometimes thought back to an earlier work I did on Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini, a relationship that at first prospered and then imploded spectacularly in the 1920s. Of his kind, Conan Doyle (a keen cricketer) was perhaps typical of the sort of instinctive patriot whose conceptions of war were shaped more by the past than by premonitions of the future. In the period from November 1914 to November 1918, he lost eleven of his immediate family members, including his eldest son, to combat or disease. Doyle, it seems to me, embodied some of the paradoxes brought about by the First World War; the creator of English literatures most famous human calculating machine, he spent the rest of his life attempting to contact dead people. I mention it just to show how the broad events treated in this book made some men and broke so many others. If nothing else, I have tried to portray the individuals seen here in the context of how they viewed the partly ludicrous, partly horrific acts of that summer, and not necessarily as we see them today. Although I hesitate to use the word enjoyable, it was a strangely absorbing book to write rather more so, I admit, than my recent biography of the Rolling Stones, a group of undoubted charm, whose essential effect on their audience could surely be reproduced by stewards walking up and down the aisles jolting random concert-goers with cattle prods. I only wish I could blame someone listed below for the shortcomings of the text. They are mine alone.

For archive material, input or advice I should thank, institutionally: The American Conservative , Blackheath RFC, Bookcase, Bright Lights , the British Library, the British Museum, Cambridge University Library, CBS News, Chronicles , Cricket Australia, CricInfo, the Cricket Society, Daily Mail , Daily Telegraph , ECB, Essex CCC, General Register Office, Gethsemane Lutheran Church, Hampshire CCC, HMS Protector Association, the Imperial War Museum, Kent CCC, the MCC Library, Middlesex CCC, the Missoulian , National Army Museum, Navy News , Pip, Public Records Office, Radley College, Renton Library, Rugby School, St Peter and Paul Church Tonbridge, Seattle Cricket Club, Seattle Mariners, Seattle Public Library, Somerset CCC, South Africa Cricket Association, Sportspages, Surrey CCC, Surrey History Centre, Takis Magazine , UK National Archives, USA Cricket Association, Warwickshire CCC, Yorkshire CCC.

Professionally: Wendy Adams, Christina Alder, Dave Allen, Jeffrey Archer, Stanley Booth, Paul Bradley, Phil Britt, Paul Brooke, Susan Carey, Dan Chernow, Kathryn Churchouse, Allan Clarke, Paul Clements, the Cricket Writers Club, Robert Curphey, Curtis Brown, Paul Darlow, Alan Deane, Tony Debenham, Andrew Dellow, Mike Dent, Michael Dorr, Lauren Dwyer, Alan Edwards, the late Godfrey Evans, Rex Evans, Mike Fargo, Tom Finn, Judy Flanders, Tom Fleming, John Fraser, Bill Furmedge, Ann Gammie, Jim Geller, Tony Gill, Freddy Gray, Ryan Grice, the late Reg Hayter, Michael Heath, Andrew Hignell, Jim Hoven, Emily Hunt, the late Len Hutton, Neil Jenkinson, Mike Jones, Edith Keep, David Kelly, Imran Khan, Max King, Alan Lane, Barbara Levy, Cindy Link, John Major, Robert Mann, Ian Marshall, the late Christopher Martin-Jenkins, Dave Mason, Colin Midson, Jo Miller, Nicola Nye, Maureen ODonnell, Orbis, Michael Owen-Smith, Max Paley, Palgrave Macmillan, David Pracy, Katharina Rae, Neil Rand, Andrew Renshaw, Jim Repard, Mike Richards, Scott P. Richert, David Robertson, Neil Robinson, Peter Robinson, Jane Rosen, Malcolm Rowley, Stephen Saunders, Paul Shelley, Don Short, Ron Simms, Ben Slight, A.C. Smith, Peter Smith, Andrew Stuart, Janet Tayler, Don Taylor, Andrew Trigg, Charles Vann, Suzanne Walker, Carol Ward, Simon Ware, Adele Warlow, Alan Weyer, Mark White, Jo Whitford, Aaron Wolf, Tom Wolfe, David Wood, Martin Wood, Tony Yeo.

Next page