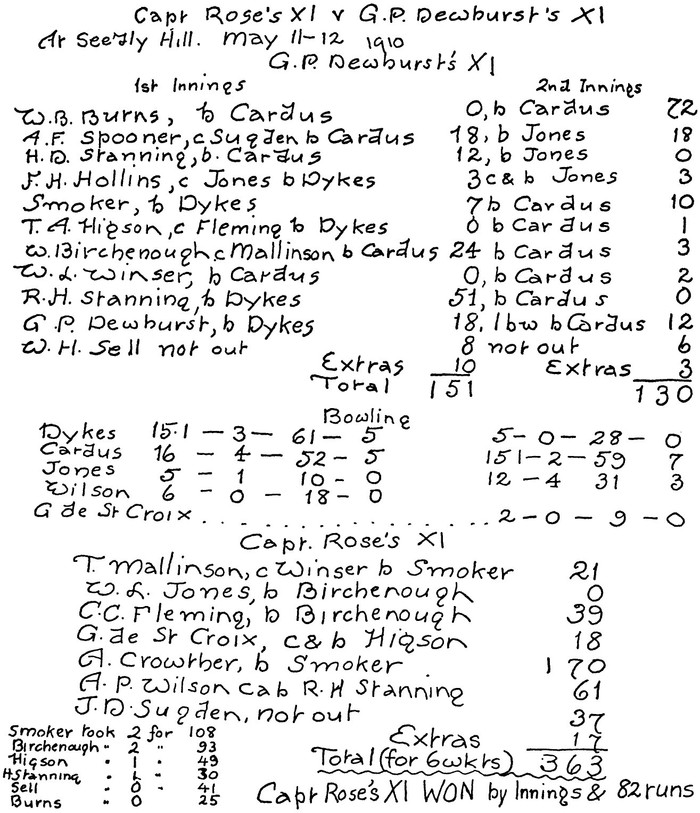

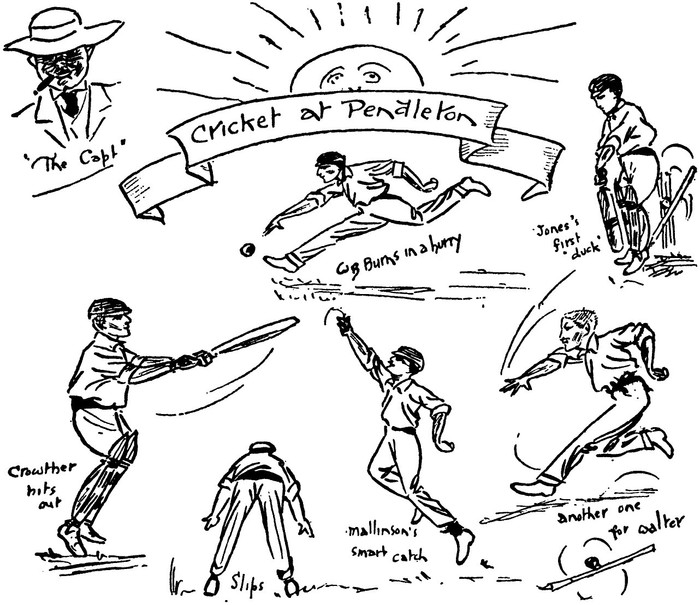

A compulsive cartoonist. Sir Neville Cardus was always drawing lightning caricatures of any subject he was discussing. The above illustration is of players in a cricket match of nearly 70 years ago in which, as a spinner, he took 12 wickets in the match.

N EVILLE CARDUS was born in 1890 at Rusholme, a poor suburb of Manchester. His maternal grandfather was a pensioned ex-policeman with lumps on his head, caused by Charlie Peaces crowbar. The family took in washing, but soon the three Cardus girls discovered that lovers were more fun than laundry-work, and much more rewarding. Nevilles father, whom he never knew, played the violin in an orchestra.

Although the boy loved his mother, and adored his Aunt Beatrice (the gayest and most extravagant of the sisters, whose brief career included a successful action for breach of promise against the Turkish Consul in Manchester), he was, as he still is, at heart a solitary, an introvert by temperament and circumstance alike. He was a delicate boy with poor eyesight, though this was not discovered until he was nineteen. After four years at a Board School, he began to gather knowledge in a wider field, and before he was fourteen he had earned money as a pavement artist, by pushing a builders handcart, by boiling type in a printing works, and as a chocolate-seller in a Manchester theatre.

At the age often he somehow discovered Dickens, and thereafter, like Silas Wegg, all print was open to him. (Dickensians will recognize an occasional echo of the Master in Carduss style to this day.) Every moment he could snatch from his various employers was spent in the Public Library or Reading Room. And then, when he was twelve or so, he first visited Old Trafford cricket ground, and saw A. C. MacLaren at the wicket. The grace and style of this great batsman fired his imagination and gave him a glimpse of aesthetic beauty in general, and the genius of cricket in particular, which was to remain with him always.

There had been no cricket at the Board School, but there were plots of waste ground, and failing all else the streets, to play on. The boy was interested in the game and was becoming something of a bowler, but it was his first sight of MacLaren, the noblest Roman, that, without his knowing it, determined the course of his life.

His next move was to a Marine Insurance office, where he worked for seven years. His salary began at eight shillings a week and worked up, by the time he was twenty-one, to a pound. On this he somehow managed to live in the back room of a lodging-house and continue his education. He attended free lectures on all kinds of subjects at the University; he went to the theatre, Miss Hornimans and others; he planned a cultural Schema of study for himself, embracing literature, philosophy, economics, comparative religion and goodness knows what; finally, he determined to be a writer.

But what should he write about? This perennial problem of youth was resolved on an April evening in 1907 when, at the Princes Theatre, Manchester, he listened to a performance of Edward Germans opera, TomJones. Even as MacLaren had opened his eyes, so did German (of all unlikely composers) open his ears. Suddenly, almost instantaneously, he comprehended music, and knew that this was his allotted theme. Thereafter, as he stood in the street opposite the ManchesterGuardian office, and he often did so stand, waiting to catch glimpses of the great men who worked thereC. P. Scott, Allan Monkhouse, C. E. Montague and the restit was the music critic, Samuel Langford, whose job he wildly and hopelessly coveted. Music was now added to the Schema, and his first published writing was an article on Bantock and Style in Music, for which MusicalOpinion paid him seven shillings and sixpence in 1910.

By 1912 the time had clearly come for him to leave Marine Insurance. By a lucky chance he answered an advertisement for an assistant cricket coach at Shrewsbury School. The engagement was for the summer term only, but he reckoned that he could save enough from his salary of two pounds ten a week to keep him through the winter. He had never, in all his twenty-one years, travelled more than a few miles from Manchester, and it was a rapturous youth who set off for Shrewsbury on May Day, taking with him his worldly goods (mostly books) in a battered tin box, his off-break, and his immortal longings.

*

He spent five happy summers at Shrewsbury, and something of the peace and delight he found there shines out from his Shastbury sketches. The old cricket pros under whom he worked, Attewell of Notts and Wainwright of Yorkshire, also reappear in his writings. One evening the head master, Dr. C. A. Alington, discovered the studious-looking young cricket pro reading a Gilbert Murray translation of Euripides under a tree, and when in August 1914 Cardus was refused for the Army, he found himself installed as Alingtons secretary.

The head masters cultivated learning, irony, wit, kindliness and sense of drama made a deep impression on Cardus, as they did on thousands of other young men. Thirty years later he said that Alington had been an influence that inspired and corrected at one and the same time; not by precept but by example, and his liking seems to have been reciprocated, for when Alington was appointed head master of Eton in 1916, he asked Cardus to go along with him.

The plan miscarried, since Cardus was liable to undergo a further Army Medical Board and, as he found to his discomfiture, no one was anxious to engage a young man who might be removed at any moment. He returned sadly to Manchester, where lack of money compelled him to accept a job as canvasser for a Burial Society. From the depths of his despair he wrote to the Editor of the ManchesterGuardian, the great C. P. Scott, asking for a humble job in the counting-house. Few editors would even have answered such a letter, but Scott immediately summoned Cardus to his home, employed him as a secretary and eventually, in March 1917, appointed him to the staff of the Guardian. A year in the reporters room was followed by promotion to the editorship of the Miscellany column and the back-page article, and then to the unexpected post of dramatic critic, assistant to C. E. Montague.

In June 1919, Cardus was recovering from an illness, and W. P. Crozier, the News Editor, suggested that he should spend a few days in the open air at Old Trafford and amuse himself by writing about the cricket. In so casual a fashion was the greatest of all cricket-writers set on his way. By May 1920 he was Cricketer, the papers full-time correspondent with a roving commission over all the cricket fields of England. And so he continued until the Second World War caused stumps to be drawn for six years.

Meanwhile, whenever there was an opportunity, he was allowed to write musical criticism as second string to Samuel Langford, and when that remarkable man died in 1927, Cardus took over. He had thus reached the happy position of being paid for doing the two things he liked best, watching cricket and listening to music. Several attempts were made by London papers to lure him from Manchester, but he preferred the freedom and the tradition of the