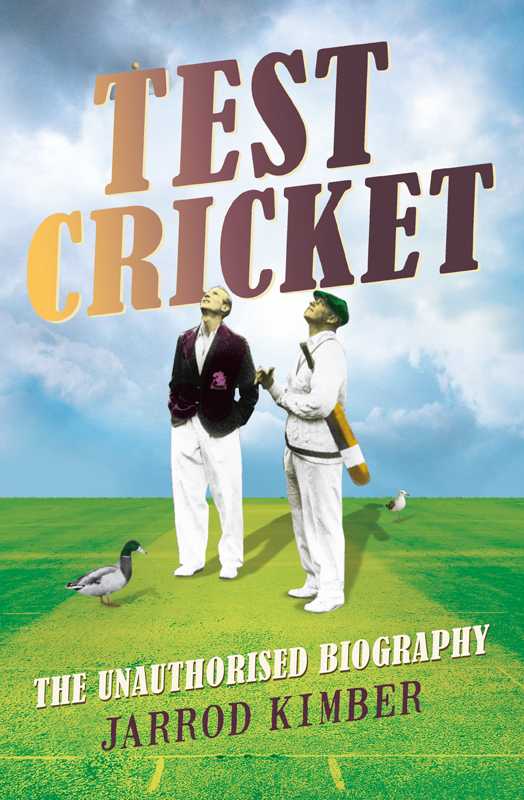

Published in 2015 by Hardie Grant Books

Hardie Grant Books (Australia)

Ground Floor, Building 1

658 Church Street

Richmond, Victoria 3121

www.hardiegrant.com.au

Hardie Grant Books (UK)

5th & 6th Floor

5254 Southwark Street

London SE1 1UN

www.hardiegrant.co.uk

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers and copyright holders.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

Copyright text Jarrod Kimber 2015

A Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the catalogue of the National Library of Australia at www.nla.gov.au

Test Cricket

eISBN 978 1 74358 323 4

Cover design by Josh Durham/Design by Committee

CONTENTS

A HAPPY BIRTHDAY BALLOON is floating at the front of Adelaide Oval on day one. Its the grounds 130th Test birthday. The balloon isnt for that.

It is for the birthday that Phillip Hughes never had. It floats above the spontaneous fan tribute to Hughes.

Underneath it is a Christmas tree. Radios. Beer. Sunglasses. Portraits. Headbands. Flowers. A toy cow. And cricket gear. So much cricket gear. Bats with rosary beads. Tear-stained balls. Kids bats. Signed gloves. Well-used bats. Pads with stories. Illustrated bats. Bats. Bats. Bats. All put out.

Team hats from clubs all around Australia are there. One from Orange. Another from the Bowen Barracudas. And the Brothers Cricket Club. There is also one from Merlynston Hadfield Cricket Club. Probably one of the hardest cricket clubs in Melbourne, a club famous for men, and boys, who batted without gloves. Their home ground seemed more frightening than the cemetery next door. One of them has donated his hat. Even the hard men are crying.

Then there is a helmet. Its hard not to think it should be on someones head instead of sitting in this tribute. On the peak is a photo of Phillip Hughes.

The condolence book is full. Bat on forever. We love you mate. Hope youre smashing them in heaven. It has far too many RIPs written in kids handwriting.

A fan walks past, takes a quick look and says its too morbid. Hughes promotional photo smiles back at him from the wall. The sort of photo that all professional athletes have to have taken has been turned into a shrine.

A memorial to a man who played cricket and was killed by cricket.

Hughes wasnt the first cricketer to die in first-class cricket. Players had died of natural causes. Club cricketers around the world have died in almost every way imaginable. Former Indian Test player Raman Lamba died when struck fielding in close. But something about Hughes, and the way cricket was now consumed globally, meant everyone remembered Hughes playing. Everyone could go online and talk about it. Everyone could, if they wanted, find the video clip of Hughes being struck.

Our game had killed someone, and no one could really handle it.

The game had been beaten, abused, choked and cheated. It had been used to racially segregate, or to keep the natives in their place. When certain players of darker skin have excelled, they have been accused of cheating. The very game itself has laws based on betting. The game has been used to exploit women, sometimes sexually or financially, while mostly mocking or ignoring them. Cheating in cricket has resulted in people going to jail. People on the way to cricket matches have been killed by terrorists. Players have been shot.

Cricket civilises people and creates good gentlemen. I want everyone to play cricket in Zimbabwe. I want ours to be a nation of gentlemen, said the brutal dictator Robert Mugabe. Mugabe and men like him have abused this sport from the day they started organising, and betting, on it. Cricket has grown into a billion dollar business. It has been commoditised and trademarked. It has been taken further and further away from where it began: just a bunch of kids bowling a ball, hitting a ball.

That was the part Phil Hughes liked. He wasnt in it to be a millionaire. He wasnt trying to build a brand. He just liked to hit the ball.

Then Hughes played his hook shot too early. The ball struck him. He went into a coma. He passed away. And the cricket world realised it was a billion-person community. A community in mourning. Remembering that little guy with the homespun technique.

One fan, Paul Taylor, had been so moved by Hughes death that he had put out his bat, took a picture, and then urged Australia to do the same. Soon, everyone did it. Millions around the world saw the pictures, took the pictures and shared the pictures. Fans put their bats outside their house, work, car all in honour of a man almost none of them had ever met.

It went viral online and it infected homes around the country and the world. People stopped while driving just to cry at the tribute. Billy Bragg put out his guitar. Google Australia put a bat leaning on its logo. Viv Richards put out his bat. Families put them out. Clubs. Factories. Everyone. Bats were bought by people just to be placed outside.

Thats cricket. Not some imaginary spirit, but something real.

Mostly the spirit of cricket is like a huge, heavy, imaginary version of the Bible. You can use any part of it to prove you are within the spirit of the game, and any part of it to prove your opposition is not. It is a magical cape that you can wear in order to tell others they are dirty cheats.

It was in the late 1990s that the MCC stuck the spirit of cricket at the start of the laws of cricket. An amendment referred to the games traditional values. It didnt say those values included class distinctions, racism and sexism. They even trademarked the term.

Months after that day in Adelaide, I was lost in the Victorian countryside looking for a wedding. There were no houses around, no one I could ask for directions. But on the corner of a fence, there was a cricket bat. I got out of the car, ran over quick enough so that snakes wouldnt bite me, and saw that the bat said, RIP PHIL. Itll be there until the wood rots.

Australia was due to start a series against India. New Zealand and Pakistan were halfway through a Test match. That Test was paused. Australias series was paused.

Cricket needed time to heal.

Out in the middle, Phil Hughes was all about batting. Whenever he thought his partner was faltering, or losing concentration, he would say, Come on, lets dig in and get through to tea.

Cricket had spent its entire history overcoming the very worst of humanity. Now it had to overcome a tragedy it created.

Cricket had killed one of the men it helped create. This time, it would be tough to get through to tea.

Y OU ARE IN LONDON; it is another millennium. You dont have enough money for the Tube. You walk across London. Its crowded and cold on this summer day in June, 1899. You travel through Hyde Park. People stand on soapboxes shouting about God and Charles Darwin. You see the recently moved Wellington Arch. You hurry down past Queen Victorias Buckingham Palace. You cross the Vauxhall Bridge, where men who dont want their faces seen scurry. You stop and give a young boy some coins as he performs a comedy routine in oversized clogs. You continue down Harleyford Road until you get to Kennington Oval.

You pay for a ticket; the price is higher than usual. You make your way into the ground, where you stand down near the pavilion. In front of you is the Oval cricket ground, behind it the gasometers. You see the two opening batsmen walk to the middle. You only smile at the thought of one of them. You are at a first-class cricket match.