B ACKWARDS

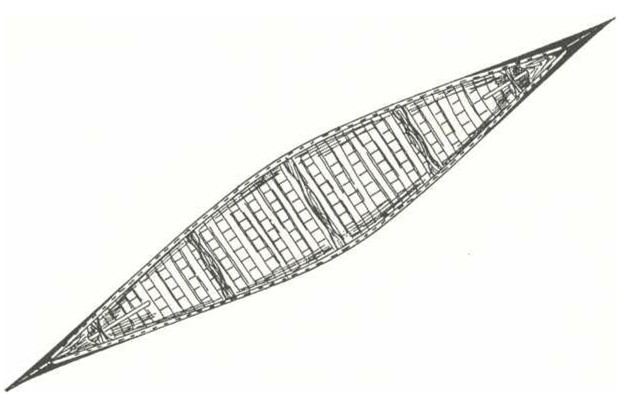

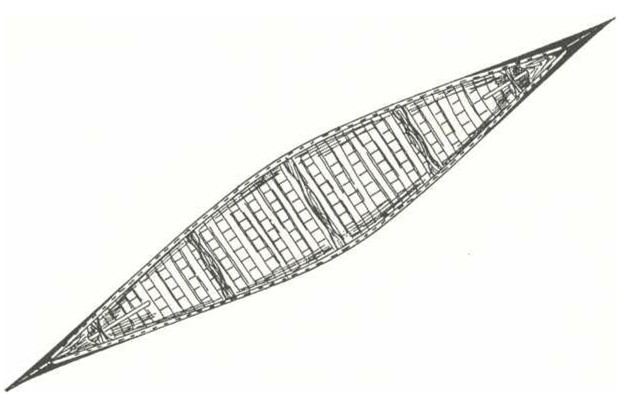

NO MATTER HOW you look at it, the traditional North American canoe is symmetrical. If you look down on it from above or up at it from below, it is widest in the middle and tapers identically toward both ends. If you look at it from the side, the sheer lines are the same at both ends. In a traditional canoe, there is no bow and no stern. Or rather there are two bows. If you put seats in the boat, then you commit yourself, and you can say, Aha, this is the front, and this is the back. You may think you know now which is bow and which is stern, but the canoe will ignore those definitions. It will respond pretty much the same way whether you are pushing or pulling it forward or backward with paddle, pole, or line.

For that, the wilderness paddler can be grateful because going backwards is often far more important than going forwards, and in the course of many maneuvers, bow and stern may well trade places. A poler may start snubbing her way down one route, decide she doesnt like it, and back up a few yards to pick another route. Or someone lining down a rapid may decide to pull his boat back upstream to set it out a little farther into the current. If direction of travel determines what is bow and what is stern, then in both these examples bow and stern have traded places. Because the canoe has a bow at both ends that trade can take place easily and instantaneously. These same simple maneuvers would be next to impossible for a square-sterned boat with its stern upstream. A square-sterned boat can be lined with its stern downstream, but the thought of poling a squareender down an intricate rapid gives me the willies. It would be a bit like trying to run a slalom course on a toboggan instead of skis.

The beautiful, brilliant, symmetrical, traditional canoe does away with all such willies. Because it is streamlined and identical at both ends, it permits precise and predictable control going forwards or backwards and eases not just poling and lining but also the backpaddling techniques needed for safe river travelbackpaddling to travel slower than the current, backpaddling to prevent shipping big waves, back ferrying to cross currents.

There is no place where the canoes ability to run backwards and forwards, upstream or down, and to pivot around its own centerpoint is more dramatically evident than in the hands of a good slalom racer. At reverse gates, slalom paddlers have to drop their boats through the gates backwards, looking over their shoulders to see where theyre going.

All these backward maneuvers are, of course, intentional, but there is also the unintentional backward maneuver, the maneuver in which your bow becomes your stern without your say-so, the maneuver in which some exquisitely camouflaged rock or some vagary of the current you had not reckoned with spins you around and sends you zipping downstreamnot through one little slalom gate but through a maze of rocks intent on having you for lunch.

In such a situation, rejoice that you are in a canoe. Remember, your boat is still traveling with one of its bows first; it is just you, not the canoe, who happens to be looking the wrong way. Relax, take stock over your shoulder, look nonchalant. The river may give you a break and let you turn yourself right way around in a convenient eddy on the way down. Or you may have to finish out the drop backwards. Either way, if youre still afloat when you reach the bottom, you can try to convince your buddies that you meant to run it that way.

Or if they havent been watching, you can just turn yourself around and pretend you ran the drop frontwards. What other boat but the traditional, symmetrical, open canoe would ever permit of such an innocent, face-saving lie?

B AGS, BOXES, BASKETS, BACKPACKS, AND THE PURSUIT OF ELEGANCE

ONCE YOUVE ASSEMBLED all the stuff you need for a canoe journey, you then have to pack it into something to get it from your living room floor to the car, from the car to the canoe, from canoe to campsite, from campsite to canoe, from one end of the portage trail to the other. What should you use? Suitcases? Froot Loops cartons recycled from the corner grocery?

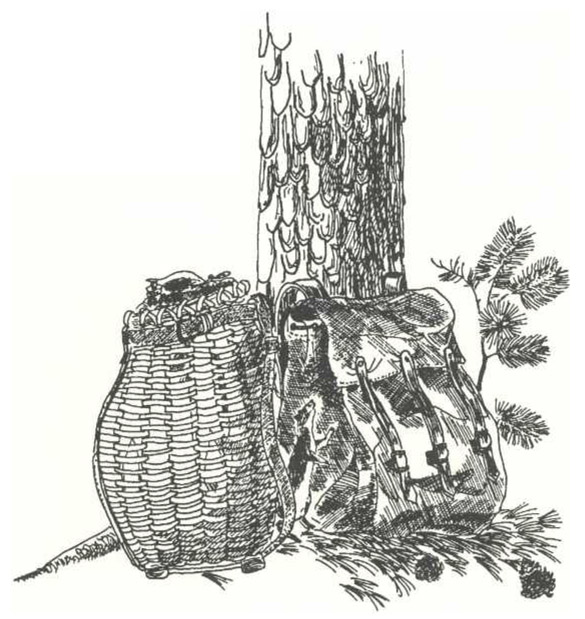

If you consult the experts, you will not find universal agreement. In The Complete Wilderness Paddler Davidson and Rugge champion the packframe, praising the padded shoulder straps, the contoured frame, and the hip belt, which all ease the carrying of heavy loads. They grant, however, that packframes are gawky things to fit into a canoe. Cliff Jacobson, in his equally authoritative Canoeing Wild Rivers, votes for the Duluth pack, praising its capaciousness, its efficient use of space in the canoe, its lack of breakable parts, and the ease of waterproofing it. He grants, however, that it is unsophisticated and uncomfortable to carry.

Faced with this divergence of opinion among giants, what is one to do? In the best tradition of the wishy-washy politician who does not want to offend either constituency, I will declare them both right and then go on to say that I and most of the folks I travel with use Duluth packs only rarely and packframes never. But let me stress once more, my fellow North Americans, that in our great pluralistic societies there are many ways to pack for a canoe trip, and the only right way is the way that works for you.

Like just about everything else in canoeing, preferences for certain kinds of packs and for packing strategies are part of a personal style that each of us develops for him or herself and that is influenced by any number of factors. What part of the country do you come from? From whom did you learn canoeing, and what packs did your teachers use? What kind of country do you usually travel? What are your personal quirks? And for any given trip, there are trip-specific questions. How long will you be out? How many are in your party? Do the rivers and terrain youll be traveling demand the lightest, most Spartan of outfits or can you afford a somewhat heavier, cushier one?

The Duluth pack is the traditional canoe pack in the Midwest. Midwestern paddlers grow up with it, learning to appreciate its many virtues and live with its few drawbacks. The woven ash packbasket is still a common sight on Maine rivers, even though Davidson and Rugge would happily consign both it and the Duluth pack to museums exhibiting quaint canoeing gear of yore. On the trip they chronicle in The Complete Wilderness Paddlerthe Maisie River in Quebectheir packframes make a lot of sense because that trip seems to call for a lot of portaging around and in and out of deep canyons. Under those conditions, ease in carrying is a top priority, and luxuries that add weight and bulk to your outfit are probably best left at home.

But if you will not be doing three mountain-goat portages a day, theres much to be said for the packbasket; and even if you are doing a lot of tough portaging and you happen to like packbaskets, as I do, you may want to put in a good word for them anyway. Just about everyone recognizes their value for carrying hard, gawky items like cooking gear and thermos bottles, which, if carried in soft packs, tend to abrade cloth and poke holes in your back. But Im partial to packbaskets as food packs, too. Lined or double-lined with rubberized army-surplus laundry bags, and with everything inside that could be damaged by water packed in Ziploc or freezer bags, they keep your stores doubly or triply waterproofed, and they float. The skids on the bottom keep them up out of the bilge water in the boat and up out of the muck in a rainy camp. Also, it is much easier to root around in a firm-sided container than in a flippy, floppy, soft pack.