1. The Odyssey of a Nice Girl

Elocution and Womens Cultural Aspirations

But under all the twisting and halting of her career she knew that there had been one thing after allthe need to satisfy the craving for something that was deep and beautiful and beyond what people called everyday things.

Ruth Suckow, The Odyssey of a Nice Girl

Ruth Suckows 1925 novel, The Odyssey of a Nice Girl , which draws on autobiographical details from her own life, centers on a young girls search for a meaningful place in the world. Marjorie Schoessel, who both plays the piano and appears as a reciter, leaves her small town to study elocution in Boston. Music, literature, and elocution fulfill Marjories longing for something real and provide her with the beauty she craves. Yet the fine arts have a complex and contradictory place in her lifewithin a limited framework they are appropriate activities for her gender and help to define her as a nice girl, but they do not allow her to have a career. Marjories odyssey, notes Karen Neubauer, is limited because of its feminine construction; it is the only kind of an odyssey a female can have and still maintain the coveted nice girl reputation. Art cannot be successfully integrated into Marjories day-to-day life, and throughout the novel her involvement with elocution creates frustrations that she is never able to overcome. On a larger level, Marjories situation allows modern readers to understand the complicated and sometimes precarious place of performing arts that became associated with women in the Progressive Era. Like Marjorie Schoessel, female elocutionists were striving to find a place for themselves in American cultural life without abandoning socially acceptable gender roles; they ultimately found their efforts rejected and their chosen art form too feminized to be considered culturally valid.

Marjorie engages with higher cultural forms because of her need for something beyond the world of her small Iowa community. Books give her a queer and elocution and music both create an audible beauty that transcends common life. Marjories first realization of deeper artistic expression comes from struggling with the Chopin nocturne assigned by her piano teacher:

Little parts, little phrases, began to take on a meaning. It was as if she had stood outside and then a door pushed open, she could see inside, and go in deeper and deeper. When people played softly or loudly, they didnt just do it because of the little marks above the measures. They meant it. When Miss Davison called for her Nocturne, she stumbled over the first bars, then all at once she knew more than she had ever known before, and the playing was easier, a kind of singing.

Elocution also allows Marjorie to approach the fulfillment she feels in music. In practicing her speeches, there was a deep new excitement in letting herself go. This gave glimpses of satisfaction, too a new possession of herself, a loosening of the tight bonds of self-consciousness and timidity.

Elocution and music are linked in Suckows novel, as they were in the late nineteenth century, through the musical vocabulary used to describe Marjories performances: both playing the piano and reciting allow Marjorie to have a singing voice. As she read poetry, words, phrases here and there, sang in her mind, brought that mingled longing and satisfaction. For women, to make art is to make an expressly feminine sound.

However, there is no appropriate place for Marjories newfound voice when she returns home, and she discovers that the distance between the higher art forms she has been taught and her small towns culture has become wider. Marjorie is now ashamed of her previous recitations. Her mother wants her to

Marjorie is conflicted not just about the content of her repertoire, but also about the act of performance itself. She is especially embarrassed by the flamboyant performance of a local woman, who melodramatically combines text with musical accompaniment:

She could not explain to themnot even to herselfwhy it was that she used to sit rigid with a dreadful shame when Mrs. Shrader walked slowly to the platform with a mystic step, opened the manuscript on her reading-stand, and read verses from The Rubaiyat with trills and sudden poundings and soft music from the piano. None of it was realonly a word here and there. And it was the very artificiality, all the palaver, that made the ladies smile at one another with a congratulatory air and think that something impressive was being done.

Marjorie recognizes not a successful female performance in the combination of the two art forms that speak to her most, but a failed attempt by women to achieve high culture, and worse, a self-congratulatory inability to recognize pretension. It is not so much that Marjories education has enabled her to transcend this world; it seems that she fears any attempt at performance on her part will simply confirm her place in it. Marjorie eventually abandons elocution and takes an office job. Nonetheless, at the novels close she is still longing for that which art has given to herthat satisfaction that was warmth in the blood, that gave life a glowing centrebut which she is somehow denied.

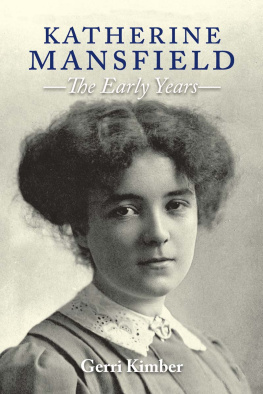

In writing The Odyssey of a Nice Girl , Ruth Suckow drew on her own experiences to create a realistic, if critical, portrayal of the role of elocution in womens lives. The small-town Iowa native personally understood the motivations behind nice girls engagement with literature and the arts, and the tensions surrounding their ambitions because of their gender. The grandchild of German immigrants, like her fictional counterpart, and the daughter of a Congregationalist minister, Ruth was surrounded by the suppers and entertainments

The world in which Ruth and other middle-class girls grew up was one in which both music and literature, made audible through elocution, represented the highest form of feminine culture. Suckow later described a parlor through a young girls eyes; at the center of the domestic sphere were signifiers she trustingly believed to set a true standard of elegancea piano with a dumb pedal, a mahogany center table with a Battenburg doily and a mottled-leather copy of Hiawatha .

Suckow apparently found her dramatic activities at Grinnell College insufficient, leaving to enroll in elocutionist Silas Currys School of Expression in Boston in 1913. The character of Marjorie was reportedly based on a fellow Curry student, not Suckow herself; nonetheless, much of what Marjorie encounters, including the specific texts that she performed, closely resembles the authors experiences. But not surprisingly, jobs directing plays in 1915 in Manchester, Iowa, with a population of just under three thousand, were not forthcoming, and the studio was abandoned.

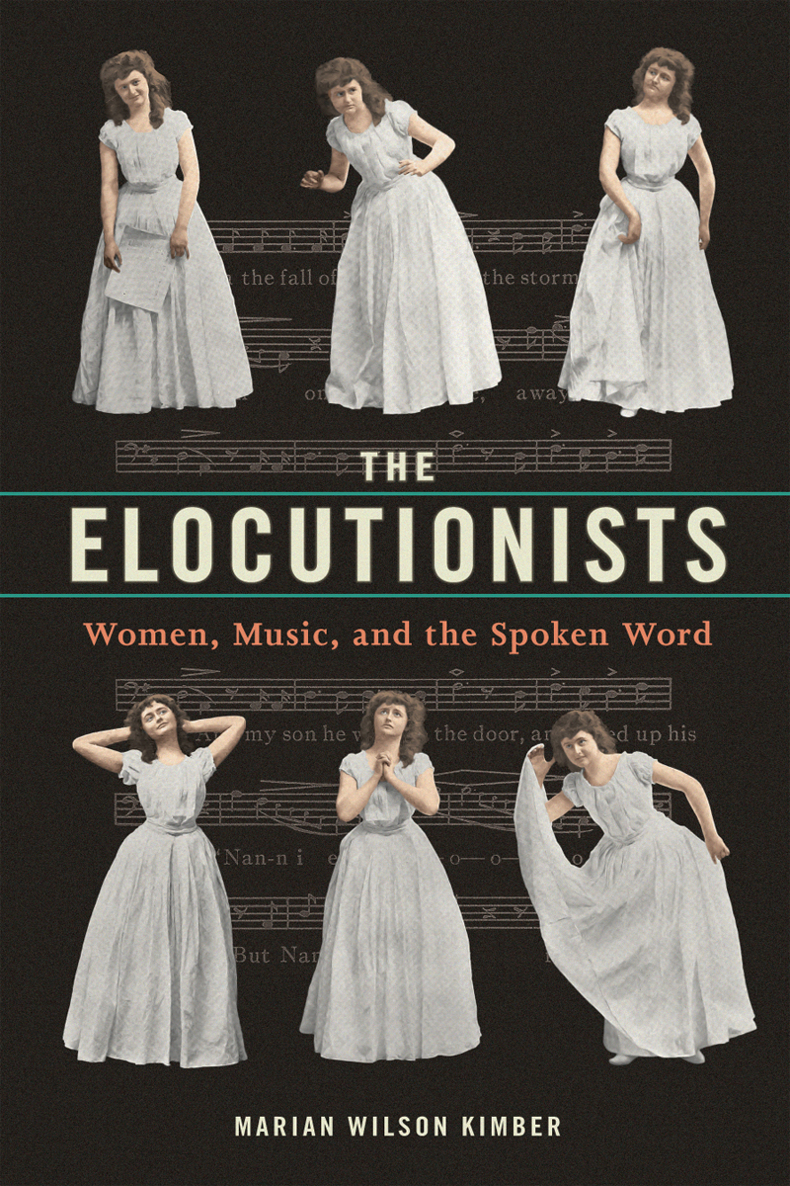

Figure 1.1. Ruth Suckow at the piano. Papers of Ruth Suckow, University of Iowa Libraries, Special Collections.

Suckow, like Marjorie and countless other female elocution graduates, did not pursue a career as a professional reader or teacher. She instead became one of the regionalist writers of the 1920s and 30s, known for her detailed treatments of life in the Midwest. Her Odyssey of a Nice Girl is not a romanticized account of one girls experience with elocutionary education; its insights into the gendered forces that shaped womens careers stem both from the authors firsthand involvement with elocution and from the widespread disillusionment with its failures after the movement had peaked. Suckow produced a novel that is achingly realistic in its understanding of what Marjorie and her nonfictional peers deeply desired, but, with hindsight, she was also cognizant of how their artistic endeavors might fail. Marjories problems are not hers alone, but are representative of those faced by women in elocution at the turn of the twentieth century; they are problems that originated with the limitations surrounding their earliest involvement with the spoken word.