This book is dedicated to my grandfather, Alec West, who brought cricket into my life; to my mum and dad, Clare and Ray, who gave me belief; to my brother, Nick, for the mix of fun and fierce combat in our backyard Tests; to all the players I played with and against; to all who watch, listen and read the game; and to my fiance, Patsy Gardner, the love of my life.

Contents

Guide

Ashley, three years old, with his mother, in Sydney, 1948.

At the age of 12, Ashley won his first state blazer for Western Australia.

Meeting Queen Elizabeth II, at Lords, 1968.

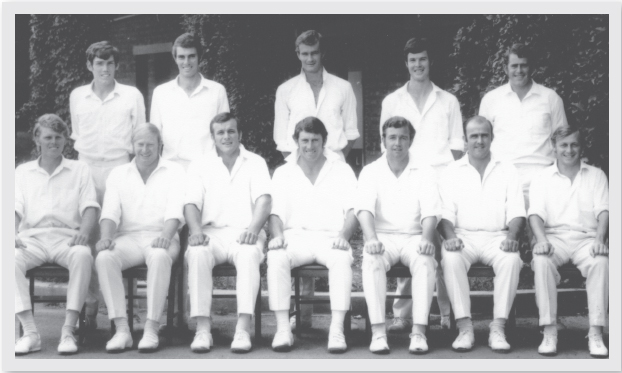

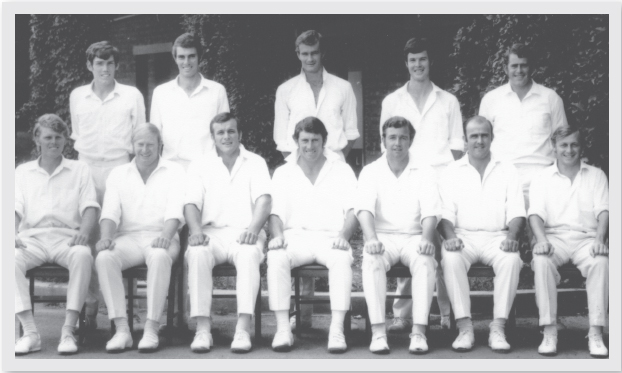

South Australias winning Sheffield Shield team, 197071.

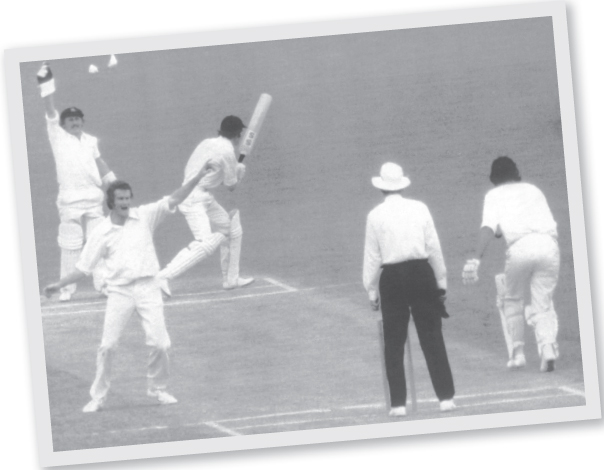

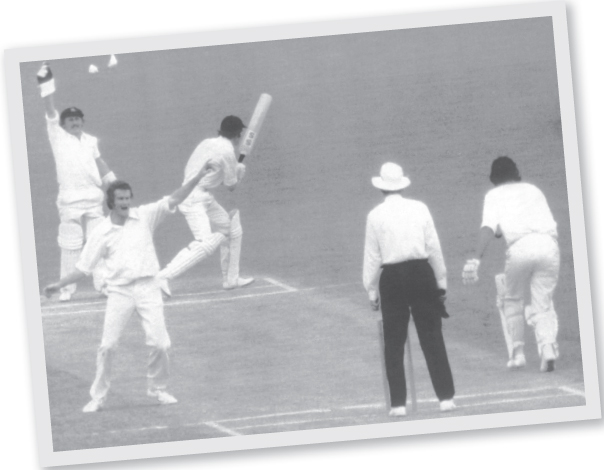

WAs John Iverarity trapped plumb lbw by Ashley Mallett, Adelaide Oval, 197172.

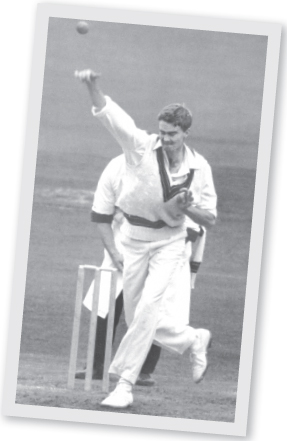

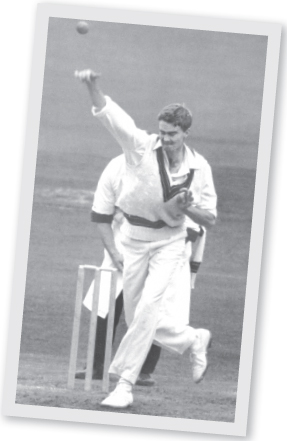

Ashley Mallett bowling for Australia versus Northamptonshire in May 1968, finishing with match figures of 10/106.

Two things fascinated me as a boy: the game of cricket and the art of writing.

From early in my life, I read avidly about the great cricketers of yesteryear, going way back to the Golden Age (18901914). I read the good writers, including the doyen Neville Cardus, who was the veritable Shakespeare among cricket writers. Cardus created a word picture so vivid that it lavishly massaged the imaginative senses. He might have been thinking about the comparative merits of Victor Trumper and Don Bradman, where Trumpers Test average of 39 paled into insignificance when put up against Bradmans 99, when he wrote: There ought to be some other means of reckoning quality in this the best and loveliest of games: the scoreboard is an ass...

Often I would stroll into a shop, pick a book up at random and read the opening paragraph. Throughout my early writing days I continued this practice. Still do. Noted novelist Ken Folletts first line in The Pillars of the Earth really sets the scene: The small boys came early to the hanging. There is a powerful brevity here; you are compelled to read on. Similarly in Frank McCourts Tis: Thats your dream out now.

From the age of six, I wanted to become a Test cricketer and, from the age of 15, I maintained that ambition to play international cricket and added another goal: I wanted to become a really good writer. In 1960, the year I finished my secondary schooling, there was a sense of conflict in me. A cricket book A Century of Cricketers, by Johnny Moyes was my constant companion, however Charles Dickenss Oliver Twist was very much a must-read, because it was the book I had picked for my English examination.

Moyes wasnt a gifted writer like Cardus, but he had the ability to bring the cricketers of his time, even those he had only read about, to life. I felt as though I knew them. So Trumper, Clem Hill, FS Jackson, Fred Spofforth, Hugh Trumble, Clarrie Grimmett, Bill OReilly, Neil Harvey, Don Bradman... all vicariously joined my cricket family. Even at the tender age of 15, to me Dickenss prose was too detailed; wordy description tended to lose the reader. I wanted to read writing which made the reader use his imagination. Ernest Hemingway certainly had that gift and so had Morris West. When the time came for me to leave school, my dear old dad had already told me, Aim for the stars, son, and you just might hit the treetops. It was a hot Perth day in December 1960 when my form teacher at Mount Lawley High School, Don Melrose, took me aside and asked me what I was going to do.

You are just 15 and about to start work in a bank. Is that the sum of your lifes ambition? he asked, with a curious pursing of the lips.

Well, Don, I am going to play Test cricket and I aim to become a good writer.

Ah... His eyes narrowed and those normally thick lips instantly became thin, brown lines. Theres no money in cricket and writing is completely out of the question, because you are hopeless at English.

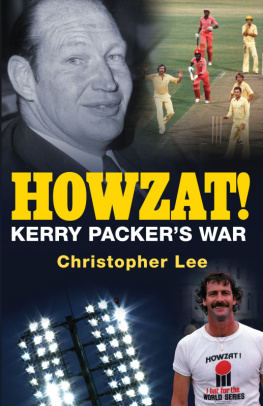

At that time, Melrose was right on both counts. Long before Kerry Packer rescued Test players and lined their pockets by bringing television to the game in an unprecedented, corporate manner, there was no money in cricket. And my English wasnt exactly tickety-boo. I couldnt fathom either the depth or the value of grammar in all its various pedantic forms.

Lunchtime at the bank was an eye-opener. In summer, the round-table conversation always embraced three main topics: sex, cricket and how to rob the bank. Winter was slightly different: sex, football and how to rob the bank.

After a few weeks in the bank, I knew I didnt want to pursue a career in the stuffy atmosphere of that august establishment. Yet the banking experience had one advantage: there was the chance to contribute regularly to the suggestion box. None of my suggestions, I might add, was ever taken up, but the exercise got me writing. Eventually I hit on the idea that if you could articulate in speech, then you should be able to write clearly and succinctly. Channel Nine and Englands Channel 5 cricket host Mark Nicholas is a fine example of someone who speaks eloquently and writes fluently.

As far back as the summer of 195455, my interest in cricket was sharpened by a trip to the Sydney Cricket Ground (SCG) with my grandfather to watch the last days play of the Test match. My grandfather, Alec West, a man who idolised Victor Trumper and was a one-time vice-president of the Balmain Cricket Club, thought it a good idea to introduce his grandson to big cricket when Australia help the whip hand. Sadly for the home team, Frank Tyson had other ideas. He ran through the Australians with a devastating display of fast bowling.

Perhaps the writing was on the wall the night before. On the penultimate ball before tea, stand-in Test captain Arthur Morris fell to a stroke that the Sydney Morning Heralds columnist Bill OReilly described as suicidally wild... a shot borrowed from kerosene-tin cricket.

While the gifted left-hander Neil Harvey batted bravely, standing up to the barrage of short-pitched deliveries arriving at typhoon velocity, Pop and I sat at the fence in front of the MA Noble Stand. On the ground at fine leg was no less a personage than Colin Cowdrey, then a man who resembled a plump, ruddy-faced schoolboy. Fourteen years later, at Kennington Oval in August 1968, he became my first wicket with the fifth ball of my opening over in Test match cricket.

In 1967, I found work as the professional-cum-groundsman at the Ayr Cricket Club in Scotland. During my stint there, I negotiated a weekly sports column with the Ayr Advertiser, the editor promising me 5. I thought that my summers 22 1500-word articles educating the Scots about the game of Australian Rules Football would net me the grand total of 110. Maybe I should have stayed in the bank after all, because the editor at seasons end presented me with a crisp 5 note for my summers writing.