The Great Romantic

Cricket and the Golden Age of Neville Cardus

Duncan Hamilton

www.hodder.co.uk

To all those who live or have lived in press boxes

First published in Great Britain in 2019 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK company

Copyright Duncan Hamilton 2019

The right of Duncan Hamilton to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

eBook ISBN 9781473661820

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

www.hodder.co.uk

contents

Prologue

Did We Really Know Him?

John Arlott introduced me to Neville Cardus; he did so twice. The first time was on television. In the early autumn of 1973

Arlott interviewed Cardus who was Sir Neville by then for three 25-minute programmes on the BBC. Each was a journey around his life and career. Cardus was in his mid-eighties, but looked much older. He looked so old, in fact, that I wondered whether the Queen would shortly be sending him a centenary telegram to complement his knighthood. He sank convivially into a high-backed leather chair, the sort you would find in the library of some distinguished London club. The chair was a shade of dark green not dissimilar to the outfield at Old Trafford after a downpour. Carduss pale face was terribly gaunt. His skin was a spidery web of broken capillaries and heavily creased too, the deep cross-hatching of lines caused by both age and a lifelong smoking habit. At one point he ran a hand over his cheeks, as though these wrinkles might miraculously be smoothed away. There was also a small indentation, beneath the left cheekbone, where overnight bristle had defeated the razors attempt to remove it that morning. Carduss lips were slit-thin. His silver-streaked hair was swept back with Brylcreem and parted on the left, exposing a high forehead. A pair of black-rimmed spectacles were looped over his large-lobed ears, which stuck out prominently.

Photographs of Cardus, even from as late as the 1950s, showed someone who at first sight could have passed for an anonymous civil servant or the assistant cashier of a bank. He always wore a light-coloured, double-breasted suit, a dark tie, tightly knotted, and a snow-white shirt. Hanging off his spindle-slender frame, the jacket could sometimes seem too broad across the shoulders and too loose around the midriff. The pleated trousers looked more ill-fitting still; indeed, it was as if hed filched them from the wardrobe of someone a little fuller around the waist and at least an inch and a half taller than him. But, thinking these set-piece interviews with Arlott could be his last in front of a camera, Cardus had greatly fussed over his appearance for them. He wanted to make an impression, rather than appear as crickets scruffy equivalent of the Ancient Mariner.

For one thing, the Radio Times was taking him on a nostalgic tour of Manchester, stopping off and snapping photographs at places pivotal to him. Among them was the modest house where hed grown up and also the site of the Cross Street offices of the Manchester

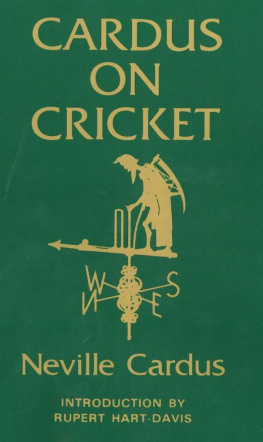

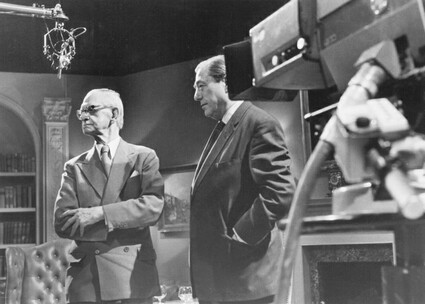

Beneath the studio lights, John Arlott and Neville Cardus chat informally before recording the BBC programmes filmed in Manchester and broadcast in 1973.

Guardian , which a wrecking ball and a bulldozer had recently reduced to dust and rubble. For another, more homes were finding the monthly rent on a colour television affordable at last. Cardus thought it sensible to get dry-cleaned one of the three identical grey suits he owned. He matched it with a blue shirt, a shiny, bright-blue silk tie and blue socks. A white linen handkerchief was folded neatly and slipped into his breast pocket, adding a sartorial flourish. He also wore, slightly incongruously, dark brown suede shoes, chiefly as a balm for aching feet.

In his later years Cardus complained that weight loss was making him slowly disappear. I can scarcely find myself in bed when I wake in the dead of night, he said. His shirt collar certainly seemed to be at least one size too big for his scrawny neck. On occasion, as Cardus nodded at Arlott or leant forward to make a point, he reminded me of a wizened tortoise, inquisitively poking its head out of its shell.

The TV critic of The Times neither appreciated nor understood the programmes. He dismissed them sourly as nothing much more than two old men sat in deckchairs. He was wrong. The conversation one master talking to another was a prime example of what John Reith, the BBCs first director-general, had originally demanded of the corporation: to inform, educate and entertain. After a while I almost completely forgot Carduss physical frailty because his voice, which seemed a generation younger than his body, performed that wonderful trick of conjuring the past.

He had witnessed the march of crickets history from a front-row seat. Hed once glimpsed the semi-retired W. G. Grace in the bulbous flesh grey-bearded and so big-bellied and arthritic that he couldnt bend down to pick up a ball. Hed sat in a state of constantly recurring astonishment as Victor Trumper played extravagant strokes, each attacking shot going off the bat with a bang. Hed followed Donald Bradman during his four tours of England, a pageant of scoring that made respectable his lust for hundreds and double hundreds.

Some of the names that swam out of Carduss memory, such as

A. C. Archie MacLaren, Johnny Tyldesley and Harry Makepeace, were then complete strangers to me, as remote as figures from medieval England. But Cardus brought sharply back something of them hed known long ago and so made the dead live again. This occurred especially when describing the man he called my idol, my hero, the imperious R. H. Reggie Spooner. He spoke in bursts of love about Spooner, compelling you to love him too.

He did so in a genteel, slightly cracked accent, more redolent of the mellow Home Counties than the industrial Manchester of rain and factory smokestacks, the landscape in which hed lived. Elocution lessons can make someone sound awkwardly stilted, as if English has been learnt as a foreign language. Cardus cultivated his voice gradually and without the need for a coach, making it seem natural rather than manufactured. Even in the mid-1920s, when radio broadcasters on the nascent BBC were required to speak as though slowly masticating crystal, his pronunciation was considered plummy enough not to frighten the nation with a dropped or crooked H. Cardus had nonetheless never forgotten what hed consciously shed. To dramatise a story, the showman would slip effortlessly into broad Lenkysheer and mimic equally broad York-sheer or cockney barrow boy, replete with rhyming slang. Hed gurn and contort his facial expressions with an actorly magnificence and gesticulate with his hands, the veins enlarged and the fingers bony. This was a theatrical performance as well as an interview.

Arlott and Cardus were born a generation apart. Cardus on the lip of crickets Golden Age; Arlott in the very year when it ended to the boom of guns from the Great War. But, as if the two of them were somehow in perfect synchronisation, the discrepancy in their ages meant that Arlott grew up and fell headlong for the game at the precise moment Cardus was in his roaring heyday, emerging serendipitously from provincial obscurity to become Cricketer, surely one of the most unoriginal noms de plume ever set in hot metal. He established himself in a wondrous rush. It was as though hed been born in a cricket press box and had glided towards fame. Precisely the opposite was true; for Cardus was the accidental cricket writer. Hed had no plan and no ambition to fill one summer after another with the sport.

Next page