Graeme Wright is a former editor of Wisden Cricketers Almanack (198792 and 200102). He is also the author of several acclaimed cricket books including A Wisden Collection, Bradman in Wisden and Betrayal: The Struggle for Crickets Soul, which was described by the Daily Telegraph as outstanding, intelligent and observant and by the Spectator as one of the most enlightened, thoughtful and disturbing books ever written on the game.

Published in the UK in 2011 by A&C Black

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc,

50 Bedford Square

London WC1B 3DB

www.acblack.com

www.bloomsbury.com

This electronic edition published in 2011 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright Graeme Wright 2011

eISBN: 978 1 4081 6513 3

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Graeme Wright asserted his right under the Copyright, Design and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

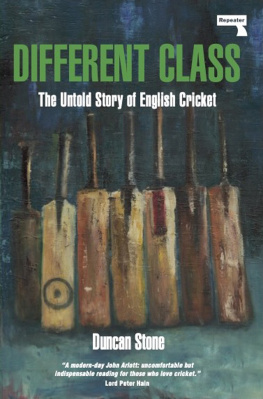

Cover photograph Photolibrary.com

Commissioned by Charlotte Atyeo

Edited by Rebecca Senior

Designed by seagulls.net

Visit www.bloomsbury.com to find out more about our authors and their books You will find extracts, author interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers

Contents

Most likely this is not the book it was intended to be before I set out to research it. I was planning something more in the line of an audit of the business of professional cricket in England. What I hadnt anticipated was the degree of distrust and even anger around the first-class counties, levelled not always at the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), as may have been expected, but at each other. I hadnt appreciated that there was as much competition off the field as on it. Conflict was a word frequently recurring in my notes.

What surprised me also was the frankness with which those within the game were prepared to speak. It was as if they saw in this book a forum wherein they could express views, ideas and concerns for which there wasnt always the time, or even the encouragement maybe, when they got together at ECB meetings. In a way, then, this has become their book rather than mine, their opportunity to put their side of the story. And because county cricket has brought me many pleasant hours in good company, I was happy to let that story run. I just stuck my oar in from time to time.

Needless to say, none of it would have been possible without the generous input of a number of people, some of whom have since left county cricket. The game will be poorer for their absence. Cricket is not that big a business really, but it is more complex and more conflicted than seems imaginable when youre sitting at a county ground, thinking the only contest is that in the middle between bat and ball. Behind the boundary, the contest is more often one of passion v pragmatism, heart v head, and thats not even the half of it.

In particular, then, I am grateful to the following for their time, conversations and, on occasions, some very good cricket lunches: Keith Loring at Derbyshire, David Harker at Durham, David East at Essex, Tom Richardson at Gloucestershire, Rod Bransgrove at Hampshire, Jamie Clifford at Kent, Jim Cumbes at Lancashire, Neil Davidson and David Smith at Leicestershire, Vinny Codrington at Middlesex, Mark Tagg at Northamptonshire, Derek Brewer at Nottinghamshire, Richard Gould and Andy Nash at Somerset, Paul Sheldon at Surrey, Dave Brooks at Sussex, Colin Povey at Warwickshire, Mark Newton at Worcestershire, Stewart Regan at Yorkshire and Angus Porter at the Professional Cricketers Association. In addition Matthew Fleming, Tim Lamb, Andrew Renshaw, David Warner and Nigel Williamson provided helpful insights, as unwittingly did county members and members of the public at different grounds around the country.

My thanks go also to my editor at A&C Black, Charlotte Atyeo, for commissioning and encouraging a book that changed direction once or twice, and especially to Paul Millman without whose help none of this would have come together in the time available. In between his commitments to Sport England and England Squash, notably chairing the selection of six Delhi Commonwealth Games medallists, he arranged all my interviews with his former county colleagues, travelled the country with me, helped analyse the conversations and read the manuscript at different stages. We had worked briefly on a project some years ago, nothing to do with cricket, and his renewed friendship was part of the enjoyment in writing on a subject, county cricket, which we both feel deserves more recognition and support than it receives.

To that supposedly dying band of supporters, the county members,

who live on from season to season, wanting nothing more than

company, conversation and a County Championship title.

CHAPTER ONE

Swansea with the Ragtop Down

Some years ago I spent my summer Saturdays covering county cricket for the Independent on Sunday. Early morning starts, late nights home, avoiding motorways when I could, criss-crossing country roads with the ragtop down. Dylan, Springsteen and Van Morrison on the tape deck. One season I tried to work a Dylan or a Springsteen reference into every match report; something to amuse the subs. Driving home, the listening would also be Radio 3, and by the Last Night of the Proms the hood was usually up, the nights were getting cold and the summer was almost done. They were good days.

Even when the cricket wasnt memorable, and too many times it wasnt, the company always was. Sport, and not just cricket, has that effect on writers whose ambitions dont stretch to far-off horizons. A well-drawn pint, the fug from freeloaded Benson & Hedges, good gossip and the opportunity to bitch about a more-favoured colleague could transform a mediocre days cricket into 500 enthusiastic words by the close of play. Back then anyway. They banned smoking in the press box, I seem to think, and looking at the papers now I get the impression theyre trying to do away with cricket writing from the county grounds. All of which is beginning to make me sound like a grumpy old man. Ive no reason to be. I know how lucky I was, and others before me were even luckier.

Covering cricket matches took me all around England. Wales, too, once I realised that the road to Gwasanaethau wouldnt get me further than a Little Chef or a BP pump. Out-grounds usually drew a good crowd and some interesting characters but, never one for camping, I preferred the solidity of a press box to a tent tucked away at long leg or deep mid-off. The ranks of empty seats at the county grounds, especially the Test match grounds, never bothered me much because my focus of interest was the cricket and the cricketers. When I did once write that there were more men carrying shopping home from Sainsburys than there were in a certain county ground, a senior cricket correspondent wigged me next day for giving the game away. Once sports editors believe that no ones watching, theyll stop giving space to county cricket, was the gist of the message. He had a point.