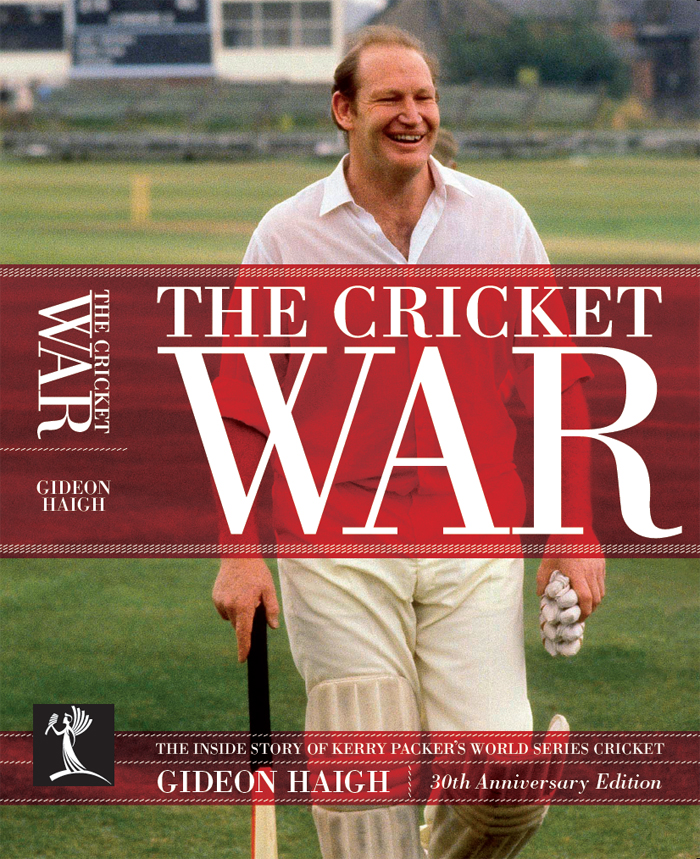

PRAISE FOR GIDEON HAIGH AND THE CRICKET WAR

There is only a handful of sports writers whose latest book I eagerly await. Gideon Haigh is one of them the most elegant and thorough exponent of book-length sports journalism in this country. Sun-Herald

In Mr Haighs research he must have worn out two or three tape recorders. Never have I read an author who has been able to extract such intimate opinions from his subjects and come so close to them The Cricket War is the most authoritative text I have read on the WSC interregnum. Frank Tyson

Haigh writes with wit, perception and a pace that rivals [Andy] Roberts. He details how the Packer revolution changed cricket forever Haighs greatest strength is the detail elicited from those who were willing to offer their memories The Cricket War is a fine example of what can be done with fine writing, thorough and imaginative research and a mature approach to sports-book publishing. Sunday Age

Cricket reading could scarcely be more compelling and while the games authorities steadfastly reject the WSC performances, the players themselves will surely be grateful for what is also an extensive ball-by-blow document of their play. Herald Sun

This book provides a fascinating insight into the behind-the-scenes moves to establish the World Series concept and the turmoil caused by its inception.An interesting and detailed account of the biggest thing to hit cricket since Dr Grace. Canberra Times

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

187 Grattan Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 1993

This edition published 2007

Reprinted 2008

Text Gideon Haigh 1993

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Ltd 2007

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Cover design by Andrew Budge

Text design by Kim Roberts

Typeset by Megan Ellis

Printed in Australia by Griffin Press, SA

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Haigh, Gideon.

The cricket war: the inside story of Kerry Packers World Series Cricket.

Rev. ed.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 9780522854756 (pbk.).

1. Packer, Kerry, 1937-2005. 2. World Series Cricket -History. 3. Cricket - Australia - History - 20th century. I. Title.

796.35865

To remember my brother,

Jasper Manton Oakley Haigh (19691987)

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE 2007 EDITION

Its fifteen years since I was involved in researching The Cricket War, at which time fifteen years had elapsed since the events it described. Yet the writing, and even the phenomenon of World Series Cricket, still feels disarmingly recent, perhaps because what seemed so uncompromisingly and vividly new then has become its own form of tradition. The cult of personality that so willingly enfolded the players of 1977 is still with us. The television formula of imposing narrative on the game and applying state-of-the-art broadcasting technology to elucidate the action is little altered: even the narrator-in-chief, Richie, and his longest serving lieutenant, Bill Lawry, remain.

Kerry Packer, of course, has gone to his rewardor, as he suspected, nowhere. But he wasnt easily replaced. His son James, who was learning cricket at the time in a household through which the worlds most famous practitioners passed as a matter of course and right, has taken up the chairmans remote control. Yet Kerrys outsized reputation seems to keep the Nine Network captive of the twentieth century, those unmistakeable features looming spectrally from Gerald Stones recent book-length obituary Who Killed Channel Nine?

In cricket, meanwhile, his name has perhaps never been more often invoked. Administrators have kept their eyes on the skies ever since, anxious that another media entrepreneur with a yen for sport should descend and make off with the best talent. The nearest equivalent were the rebel tours of South Africa between 1982 and 1989, which plundered players from England, Australia, the West Indies and Sri Lanka, although these offered no head-to-head competition with the established game on its own soil. Although Rupert Murdoch cast a long shadow over Australian cricket in the aftermath of his formation of rugbys Super League, he was content merely to spook everyone in cooee. Now, in the form of the Texan billionaire Allen Stanford and Subhash Chandra of Zee Telefilms, we are watching the formations of new professional tours. Even the reaction of the authorities is tempered by the lessons of World Series Cricket, Packer having proved that cricket is a premium media franchise. The churchmouse-poor West Indies Cricket Board feels it might gain from making space for a savvy businessman; the filthy-rich Board of Control for Cricket in India believes it has too much to lose from the division of its lucrative market.

Stanford and Chandra, moreover, have proceeded in unconscious emulation of Packer by basing their enterprises on the games new Twenty20 variant, just as Packer thirty years ago homed in on 50-over cricket, hitherto underexploited, as the growth end of the market. The International Cricket Council has also learned its lesson. Where the establishment in 1977 stood back in consternation and let Packer make use of the limited-overs template they had pressed, the ICC has this time staked out its turf with the recent World Twenty20 Championship in South Africa. But we can expect more of the same, explained with airy invocations of Packer, who made the unthinkable thinkable: that men would play for money rather than merely for national pride.

Sometimes it is argued that the establishment should have seen Packer coming; that World Series Cricket was inevitable. The statement is essentially weightless. The end of the world is inevitable. That does not mean we must begin planning for it. Ones death is unavoidable. But from this it might be inferred that one should live for the presentand this is what crickets authorities chiefly did. In the 1970s, world cricket was a group of autarkic city states, whose overriding end was raising sufficient revenues to cover their operating costs, and whose honorary administrators were strangers to strategic planning. It was a system little changed in a hundred years, and systems enduring so long might as well carve their by-laws into clay tablets for all the likelihood of their voluntary revision. Since The Cricket War, I have been involved in writing the official history of Cricket Australia, previously the Australian Cricket Board. It is striking just how precisely the external impression of the organisation tallies with its internal workings: its ink-dense minutes are like reading those of a big cricket club, absorbed in minutiae, building by accretion, taking it one season at a time, assuming that thered always be players, confident thered always be fans.

Its truer to say that World Series Cricket originated in an enduring tension. In its pioneering days, Australian cricket was a players game. The original tours of England were entrepreneurial expeditions, returning home laden with honours and financial spoils. The players, with the commercial and moral support of the powerful Melbourne Cricket Club, were mainly their own masters. That changed with the foundation of the Australian Board of Control for International Cricket in May 1905. The eighteen months of wrangling that ensued subdued the players and marginalised the club, capturing the proceeds of Ashes competition for the gameor, at least, the game as it was constituted by the state associations whose members composed the board. With the Big Six dispute of 1912, when Australian crickets half-dozen leading exponents stood out of a tour of England because the Board had denied them their choice of manager, the players were permanently shut from the games organisation. I well remember Ian Chappells words when I was talking to him about