INTRODUCTION

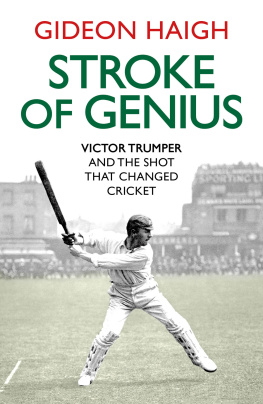

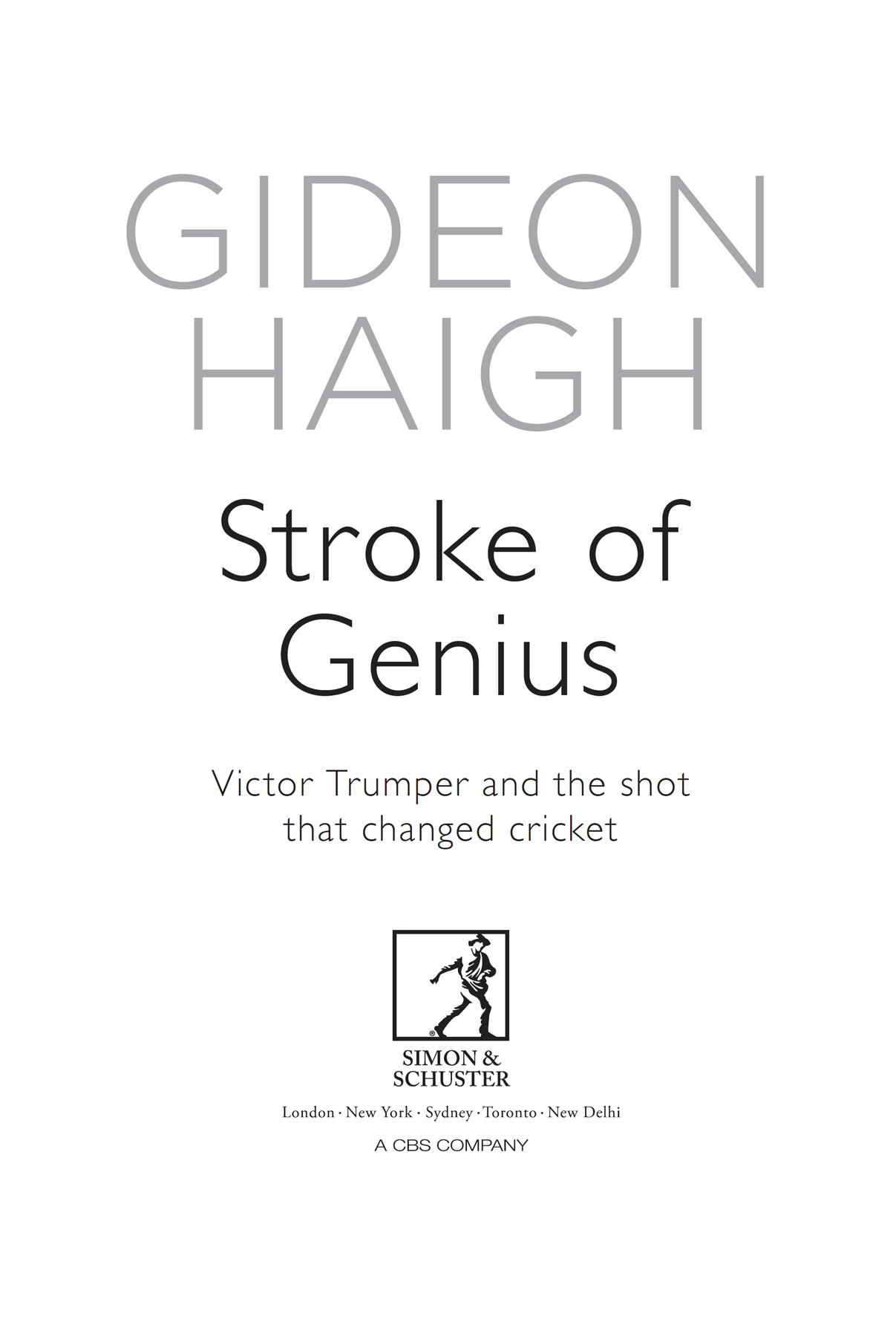

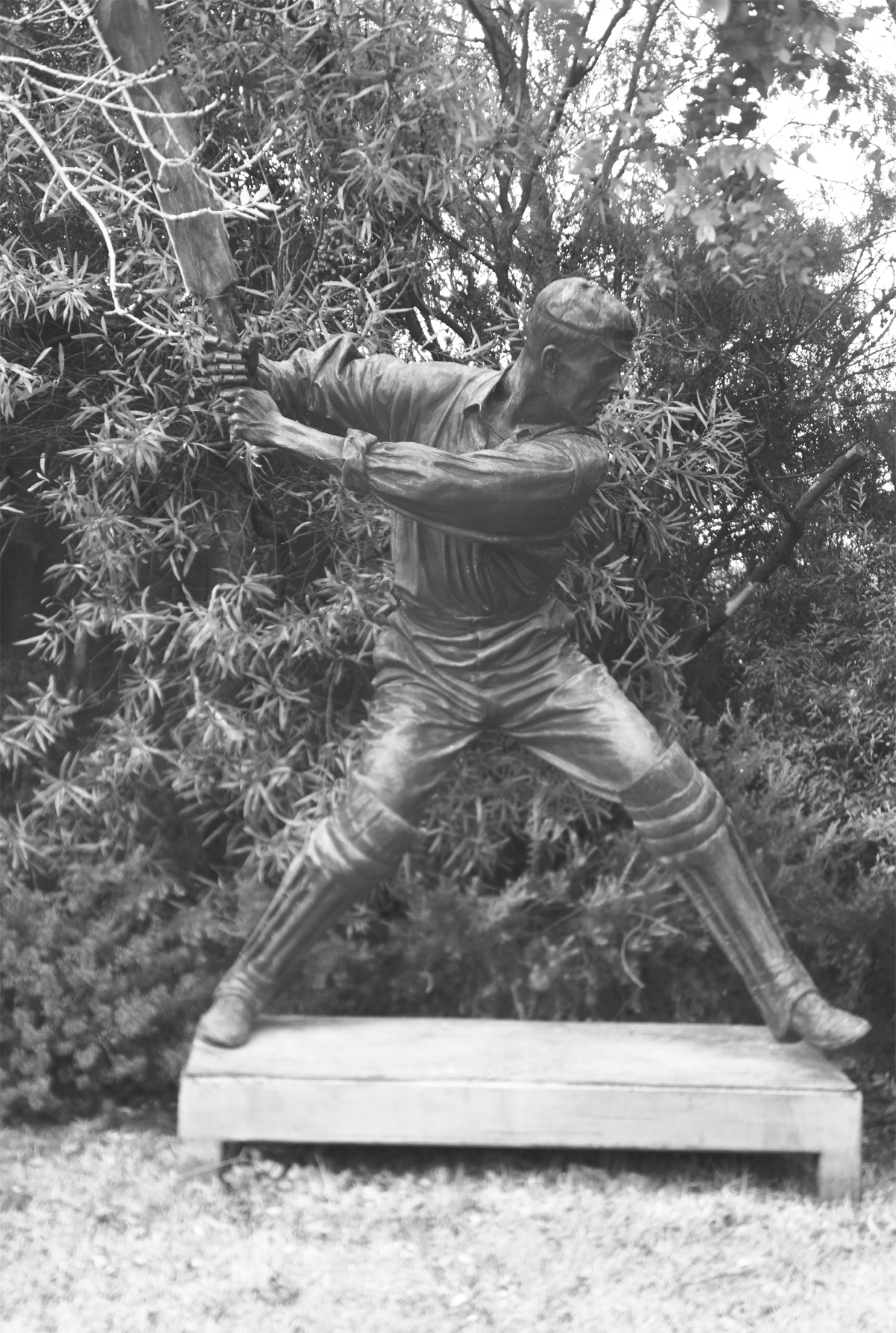

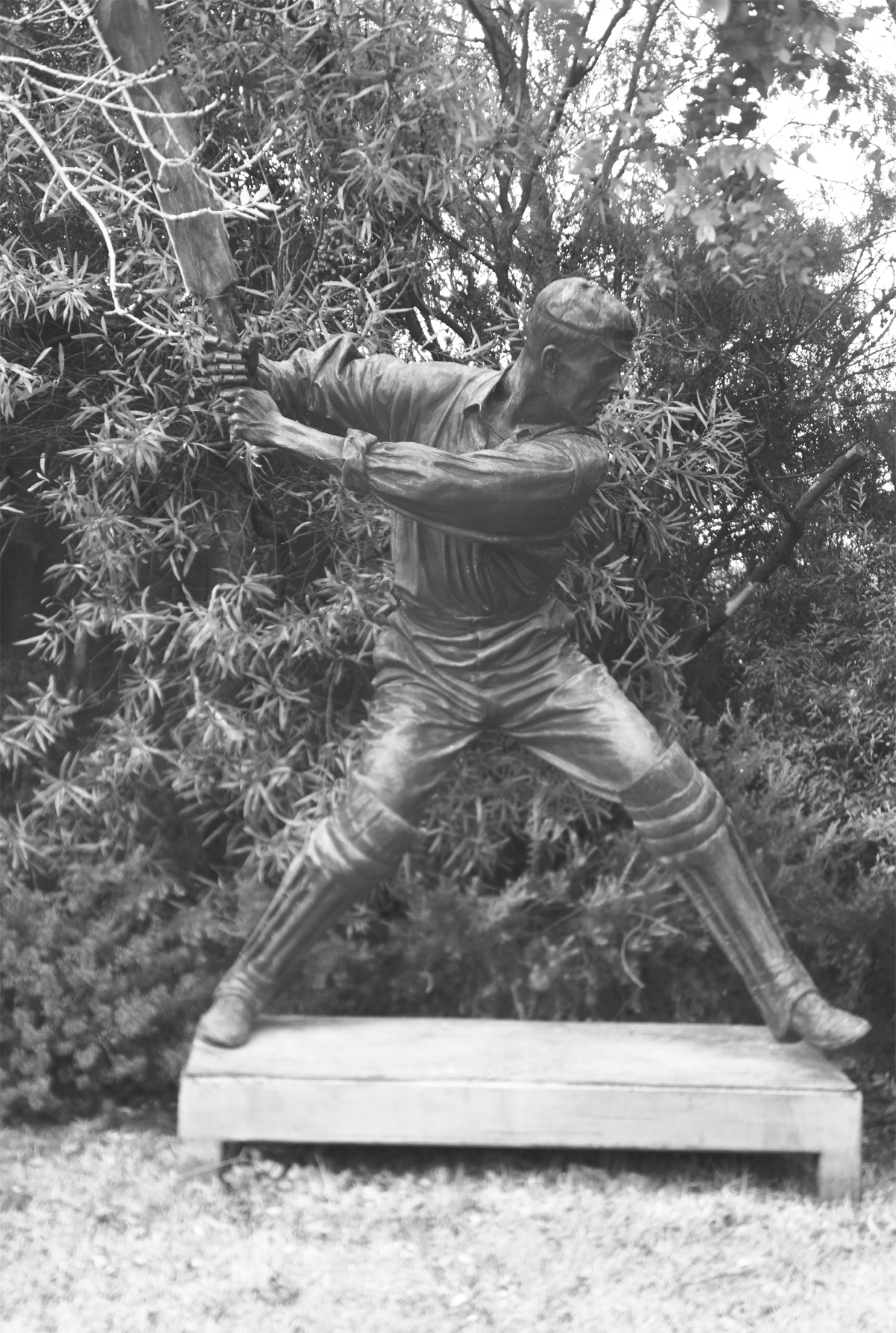

The batsman appears almost airborne. Only the instep of his back foot remains grounded; the front foot hovers in space, destined never to land. Yet there is no sense of strain only energy and expectation.

His figure is spread, as if involved in a Vitruvian exploration of battings physical limits. His bat, slim, loosely gripped, is at the commencement of its downswing. The muscles of his left forearm are taut with pent-up power. His cap is tugged low, accentuating the precision of the gaze.

His clothing is generous, yet contoured to the hips and shoulders, expressing their purposeful geometry. His sleeves are folded just so, distinctively below the elbow, a personal signature. His legs are lightly sheathed in slatted pads, but theyre purely for forms sake. All that matters is the imminent interaction of the bat with a ball were left to imagine. Nor are there fielders, stumps, crowd. Rather is he fringed by a full-grown wattle, in the corner of a vineyard.

For I am regarding not a photograph but a statue. A hundred years after the death of Victor Trumper, Ive inched my way along Victorias Mornington Peninsula to Red Hill in search of a 2.5-metre-tall bronze cast of him to be precise of an image of him, perhaps the most famous image in all of cricket, and certainly the image famous longest.

Bronzed Aussie: Trumper by Louis Laumen.

Crafted in 1999 by the sculptor Louis Laumen at one and a quarter times lifesize, it was acquired through the auction house Christies by a successful bookmaker, David McLachlan. For almost as long as he has been the owner, McLachlan has been wondering what to do with it. He has no interest in cricket; he acquired it as an investment, during a dabble in collecting. Having twice failed to sell it, he lent the statue to a developer friend, Neil Bryson, who owned a vineyard with its own little cricket ground. For a few years it provided a talking point for guests at an annual match for Brysons friends. The statue moved to its present whereabouts, by truck and crane, when that property was sold.

Other plans have come to McLachlans quicksilver mind from time to time. Some have been grand, such as placing it in the forecourt of a residential development to be called Trumper Towers. Some have been more rococo, like drilling a hole in the sculptures head and turning it into a swimming-pool water feature. More recently, hes thought differently. For a while, I was a bit embarrassed about it, McLachlan says. Id bought it to make a few grand and it was kind of a failure. Then a note of surprise enters his voice. But Ive got to admit, Ive fallen in love with it.

For more than a century, crickets votaries have been doing the same, at first because of who the image depicted in its original two dimensions, increasingly because of what it has become according to sources as diverse as Wisden Cricketers Almanack and Wikipedia, an icon.

Victor Trumper would have been an iconic figure anyway. He was the first truly Australian sporting hero, in the sense of having an actual nation to represent, and being the best at the sport that to his countrymen mattered above all. He also formed part of a profound moral and aesthetic revaluation of cricket, an awakening to its potential beauties, an invitation to appreciations deeper than runs and wickets, victory and defeat. And after his death, he became the first Australian athlete around whom a truly lasting legend was built, remaining lodged in public affection even through decades of Bradmania, despite there being no significant book about him, no public monument to him of any description, no all-encompassing mass media to inundate the senses with messages of his greatness.

What existed, however, was this photograph the most durable, and still among the most popular, of a great sportsman in action. Trumper remains accessible through certain canonical writings moving elegies in the autobiographies of teammates Monty Noble and Frank Iredale, lavish panegyrics among the works of Sir Neville Cardus and Jack Fingleton. Yet Trumper is the earliest sporting luminary to have been, in the main, visually bequeathed: he is as much his picture as Sir Donald Bradman his statistics, and perhaps even more so, as what first illuminated then complemented Trumper has almost replaced him altogether, culminating in its final transfiguration into an art object, inspiring paintings, prints, plates and figurines, helping to sell beverages and bands alike.

Despite this, the achievement of the images creator, George Beldam, an accomplished amateur batsman and self-taught photographer, has languished in near-total neglect. He was the first skilled practitioner to devote concerted attention to sport, speaking of Action Photography decades before the expression enjoyed widespread usage, and his picture of Trumper predates by generations those Australian sporting images that vie with it for fame, such as the climax of the Tied Test (Ron Lovitt), Norm Provan and Arthur Summons at the SCG in 1963 (John OGrady) and Nicky Winmar at Victoria Park thirty years later (Wayne Ludbey).

By subordinating text to illustration, Beldams books Great Batsmen and Great Bowlers and Fielders, in which Trumper and scores of his contemporaries go through their paces, completely reversed sports traditional descriptive economy. Then, almost as quickly, Beldam diverted his autodidacts gaze to competing enthusiasms. A photogravure of what was originally Plate XXVII: Jumping out for a straight drive on page 124 of Great Batsmen hangs in Australias National Portrait Gallery; artworks derived from other of his photographs hang in Britains. Yet Beldams oeuvre remains uncurated and uncatalogued; a sizeable proportion of his plates have never even been printed.

Partly in consequence, it remains a mystery how the paths of Trumper and Beldam originally interleaved. None of the photographs Beldam took of Trumper are dated; neither man recorded impressions of the experience; the original of Jumping Out appears to have been destroyed, accidentally, by Beldams youngest son. Mind you, when versions have reached the scale of a quarter of a tonne of silicon bronze reinforced by steel rods, that loss hardly seems so injurious. And that the image marks no special innings and relates to no particular match may account for some of its durability: it conjures an era, an attitude; it both harks back to crickets first visual imaginings of itself and anticipates a present day where action can be arrested by a keystroke. That front foot is still to land, just as there is always, in cricket, something about to happen.

Although this book has biographical elements, it is not a biography of Trumper. Three biographies give chronologies of his life, collate reportage of his innings and sentiment about his personality. Stroke of Genius is instead, for want of a better word, an iconography, a study of Trumpers valence in crickets mythology and imagery. E. B. White famously likened humour to a frog: Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process. The same risk may be thought to apply to sporting legend. Thats far from my purpose: on the contrary, Trumpers is a legend to which I have been attached as long as I can remember.

Like many people, I encountered Trumper and Jumping Out simultaneously in my case on page 89 of one of my earliest cricket books, a slim paperback called Great Australian Cricket Pictures (1975). The reproduction was poor, the caption terse and uninformative. But to it I went back and back, as can be judged from the fact that my copy today falls open at exactly that page. Such a dashing stroke. Such a vivid image. Such a musical name, too. Neville Cardus wondered aloud about the rightness or otherwise of cricketers names after reading an evening stop press of a good score by a Worcestershire wicketkeeper called Gaukrodger: With such a name he ought never in this world to have been permitted to score 19, let alone 91. It gave him a renewed appreciation of his schoolboy hero: Had Trumper been named Obadiah he could scarcely have scored a century for Australia against England before lunch.

Next page