CONTENTS

W.G. The Champion Grace

After the publication in 2010 of The Captains, an interviewer asked me to delve right back into cricket history and talk about some of the early characters of the game. With relish, I began to talk about Dave Gregory and Billy Murdoch, Australias first two Test captains. Quickly I was interrupted: by cricket history my questioner meant the Chappell years, or, if I wanted to go prehistoric, maybe Richie Benaud?

This obscuring largeness of the present is not unusual. Most cricket appetites are fully satisfied by what can be consumed right now. History is ones own memory, whether that reaches back to the time of Steve Waugh, Allan Border, Lillee and Marsh, or perhaps Lawry and Simpson.

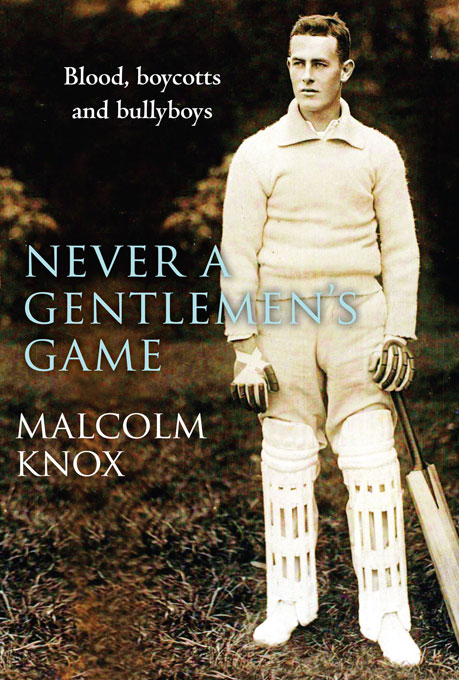

Even for the devoted cricket fan, history might reach back to Don Bradman and Bodyline, but not much further. As a cricket-mad child, I had skated over the Jurassic that is, pre-photographic age of cricket without curiosity. The nineteenth century featured a handful of eccentrics W.G. Grace, the Demon Spofforth, the expansive Victor Trumper of George Beldams 1902 photograph and there was the punch-up between Clem Hill and one of the selectors. But for the most part, the early days were sepia-tinted times, recorded by sepia-tinted men.

The present day also provided enough controversy, seemingly unprecedented: match-fixing and gambling, throwing, gamesmanship pushed to the brink of cheating, national teams being broken apart by Realpolitik, and, as a steady undertow, the wrenching inequalities of crickets income and the vicious power of money to bend or break any principle.

When, while writing The Captains, I went back to the early days of Test cricket, I expected a tranquil backwater. Those sepia-tinted pioneers were playing for pure competition and camaraderie, lower stakes than now. Even the controversies must have been sporting matters, fought under Queensberry Rules and settled over a glass of port. I thought I was returning to the world described by Lord Harris, the first baron of international cricket: It is natural that a people so devoted to sport and pastimes as the British should have brought sporting expressions into their phraseology, but that one pastime should be picked out by common consent as descriptive of all that is straight, fair, and honourable is a very extraordinary, indeed I think I might claim an unrivalled, distinction.

Of course, Lord Harris and I couldnt have been more mistaken. Cricket between the 1870s and 1914 was riven by match-fixing and gambling, throwing, gamesmanship pushed to the brink of cheating, national teams being broken apart by politics, and, as a steady undertow, the wrenching inequalities of crickets income and the vicious power of money to bend or break any principle. In fact, todays controversies have been on a repeatcycle, except perhaps for a moment, half-illusory, nostalgia-fuelled and by no means limited to cricket, where the belle-epoque spirit of Edwardian times really did pervade the game. This idea of cricket was put forward by the most literate of the Edwardians, Charles Burgess Fry:

Anything that puts many very different kinds of people on a common ground must promote sympathy and kindly feelings The game is full of fresh air and sunshine, internal as well as external One gets from cricket a dim glimpse of the youth of the world.

That was of course Frys idea, just as the straight, fair and honourable was for Harris, a glow nursed late at night rather than a reality witnessed on a cricket pitch. Harris was extolling the honour of cricket from old age in the 1920s; he must have forgotten his involvement in a serious cricket riot and his subsequent role in boycotting uncouth Australians from playing at Lords. He must have forgotten his campaign to root out an epidemic of throwing. He must have forgotten his ruling that a dark-skinned man born in India could not play for England.

The truth is that Anglo-Australian cricket up to 1914 was cricket in the raw. The disputes that subsequently became swallowed up in euphemism first of sportsmanship and social prestige, then of corporate weasel-speech were, in those early years, played out directly. When one cricketer had a problem with another, he did not background his media mates or manoeuvre with agents and sponsors. He punched him in the nose. When the Australian captain had a problem with his counterpart, he did not write a match report or tell a press conference it was disappointing. He rushed out and confronted the man, in front of tens of thousands of spectators vociferously taking sides. When bookmakers wanted to corrupt players, they actually used brown paper bags. There was a refreshing absence of the codes of obfuscation we are forced to interpret today. Things were upfront and honest. Violence was physical, not metaphorical.

The controversies we see today have been played out before. By examining history, we can see where our current disputes are headed and how, perhaps, they may be settled. History provides not just data, but current strategy.

The other prejudice about the sepia days is against the cricketers themselves: lets face it, they cant have been very good, can they? Weve all seen pictures of a Grace or Murdoch with their quirky stances, Trumper with his slatted pads (and his Test average of 39), Spofforth and his old- man action (never mind that the Demon was 50 when photographed, 23 when he first tore England apart). Really, such judgements are instinctive but also plain dumb cricketers can only be assessed by the standards of their age, otherwise you end up arguing such nonsense as Mitchell Johnson would be harder to face than Charlie Turner and Michael Clarke hits harder than Clem Hill. If we put aside the rank stupidity of infatuation with the present, and look a little more closely at the distant past, taking into account the customs of photography just as every person frowned in the first photos, cricketers were told to take up those stiff postures there is a glimpse, now and then, of how skilled the early players actually were.

My epiphany came from a photograph of W.G. Grace in the nets, taken by Beldam late in the Champions career. He is playing a forcing on-drive, which he has hit on the up, and if not for the net the ball would be zinging between mid-wicket and mid-on. It is a fiendishly difficult shot to play well, requiring a high elbow and perfect timing and balance. Grace in that photo is anything but the odd-looking poseur with the upturned toe and idiosyncratic grip in staged portraits. In action, his every moving part is in perfect place. A master stylist of our time, a V.V.S. Laxman or a Ricky Ponting, would have feet, wrists, bat and weight in the same position as Graces. What tops it off is the balls location. It is flying downwards into that probable gap. You see that, one, Grace has timed it superbly, and two, for him to play the shot he has played, with his hands and bat and body in the position they are, the bowler must have been a reasonable pace. No dodgy round-arm trundler here: you sense that when veterans of the Golden Age said C.J. Kortright, Arthur Mold and Ernie Jones were as fast as Larwood who we know, thanks to moving pictures, was as fast as anyone since they were not exaggerating.

Cricket was never a gentlemens game. It was a brutally competitive affair played with desperation for the highest stakes. The rudest illusion of the current day is that there is more at stake than there used to be. The following pages should lay that to rest.