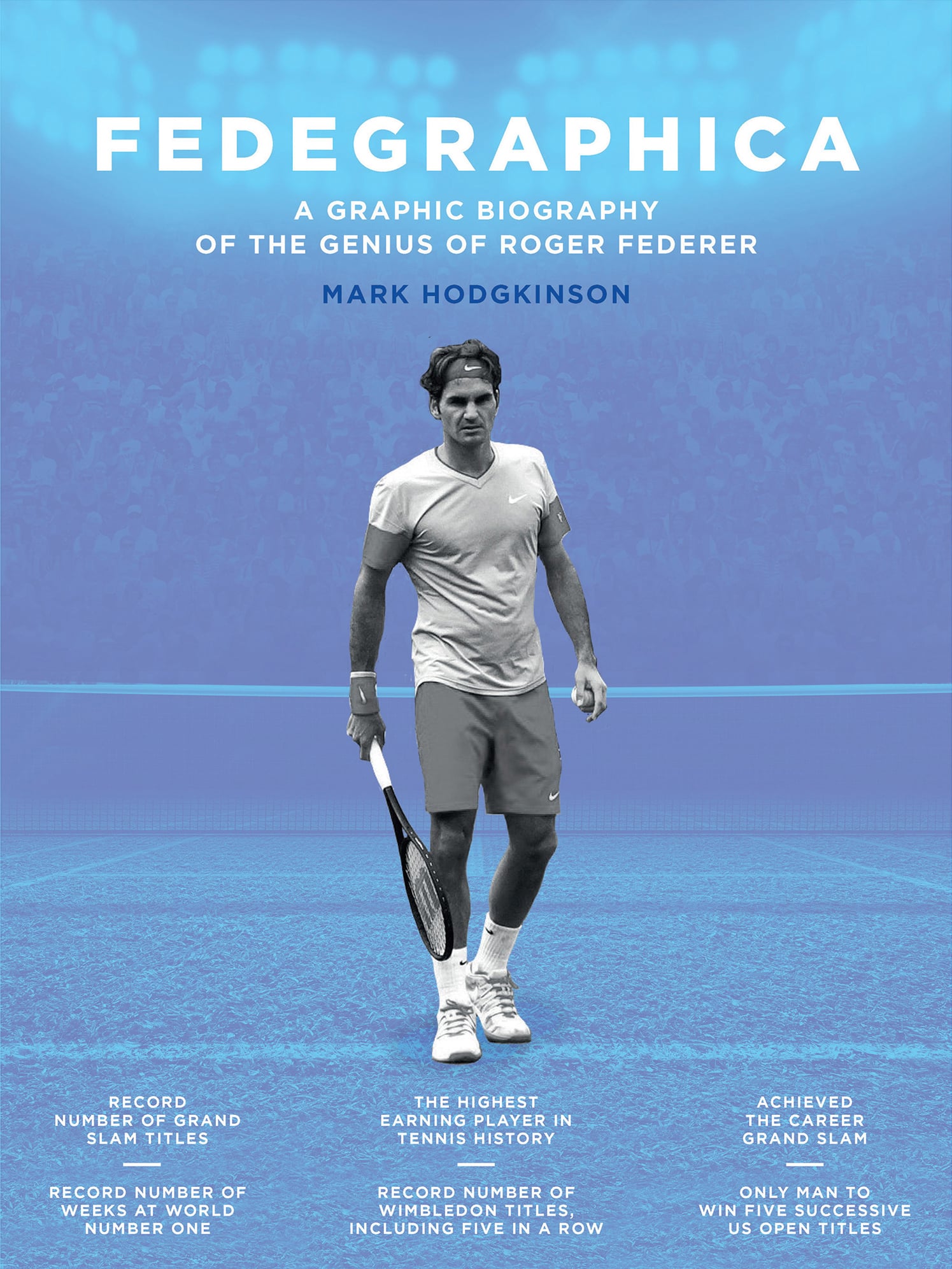

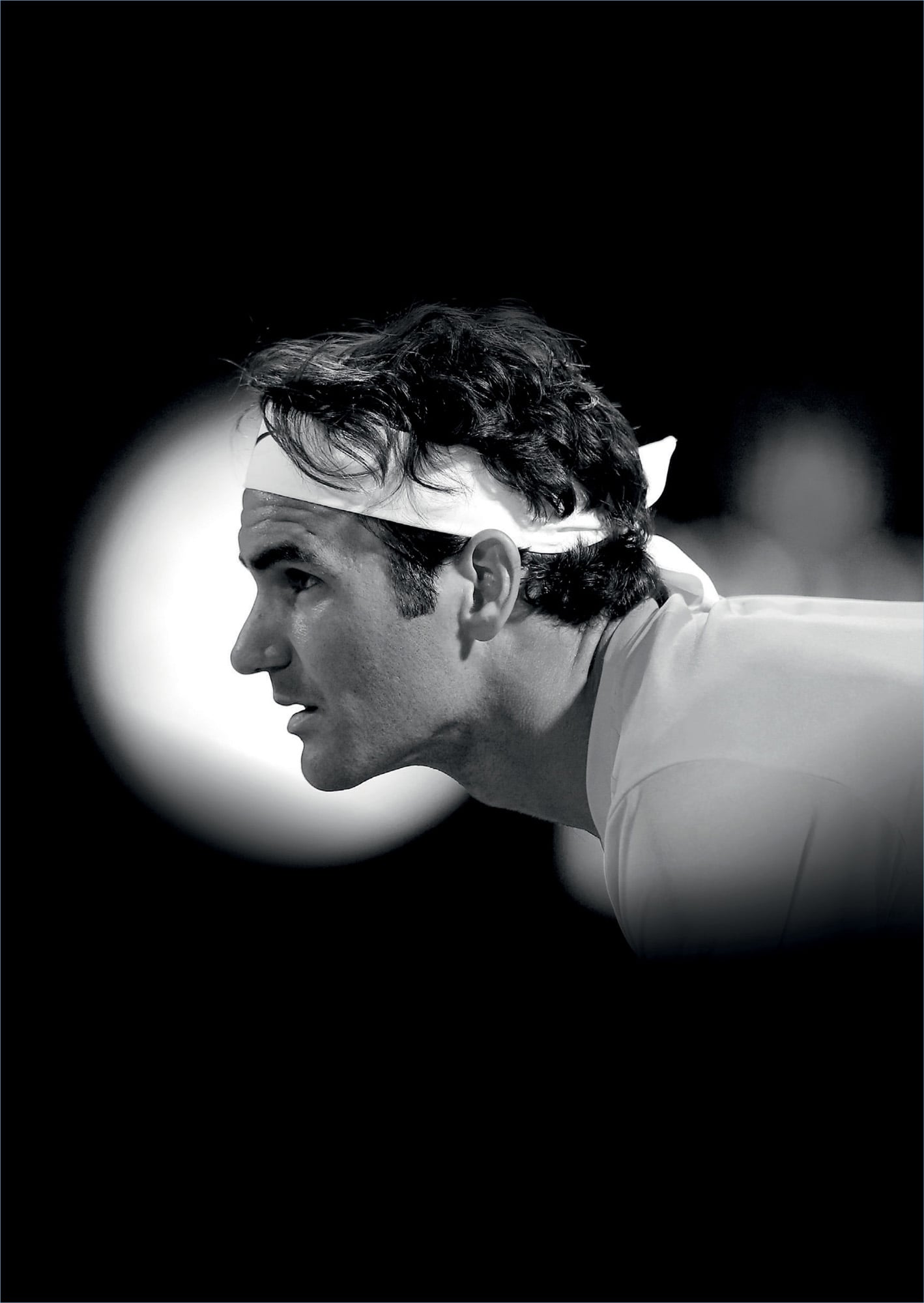

FEDEGRAPHICA

A GRAPHIC BIOGRAPHY OF THE GENIUS OF ROGER FEDERER

First published in Great Britain

2016 by Aurum Press Ltd

7477 White Lion Street

Islington

London N1 9PF

Text copyright Mark Hodgkinson 2016

Digital edition: 978-1-78131-609-2

Hardcover edition: 978-1-78131-529-3

Mark Hodgkinson has asserted his moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Aurum Press Ltd.

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Design: www.fogdog.co.uk

Infographics by Paul Oakley and Nick Clark

CONTENTS

Guide

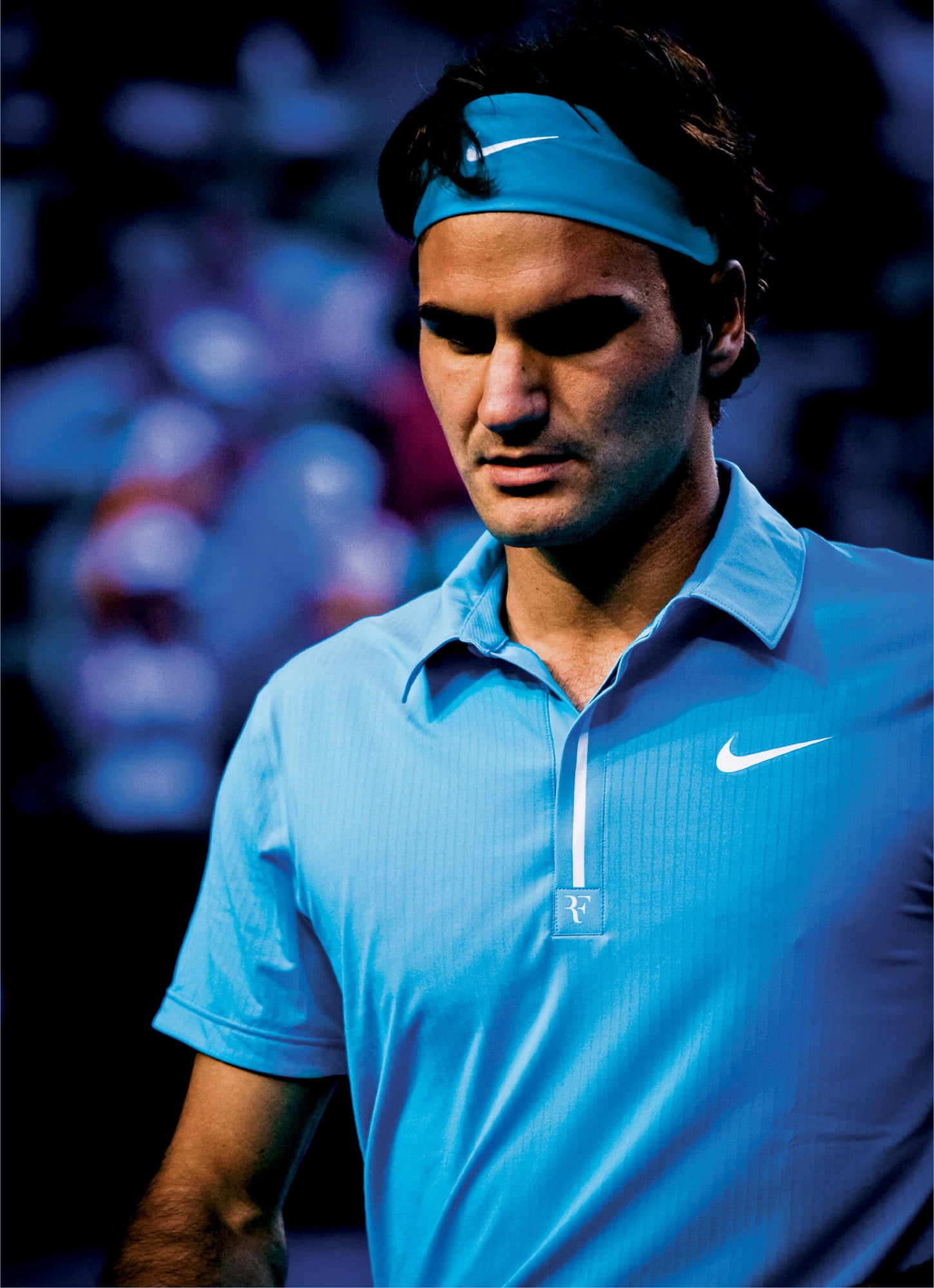

YOURE

WATCHING

TRUE GENIUS.

HES THE

GREATEST

PLAYER

THATS EVER

LIVED.

JOHN MCENROE

PROLOGUE

R oger Federers mid-life experimentation and reinvention came, of all places, in old cowboy country, on the concreted-over plains of Ohio. Or, to be more precise, in Mason, outside Cincinnati, on the other side of Interstate 71 from the Kings Island amusement and water park (The Biggest in the Midwest).

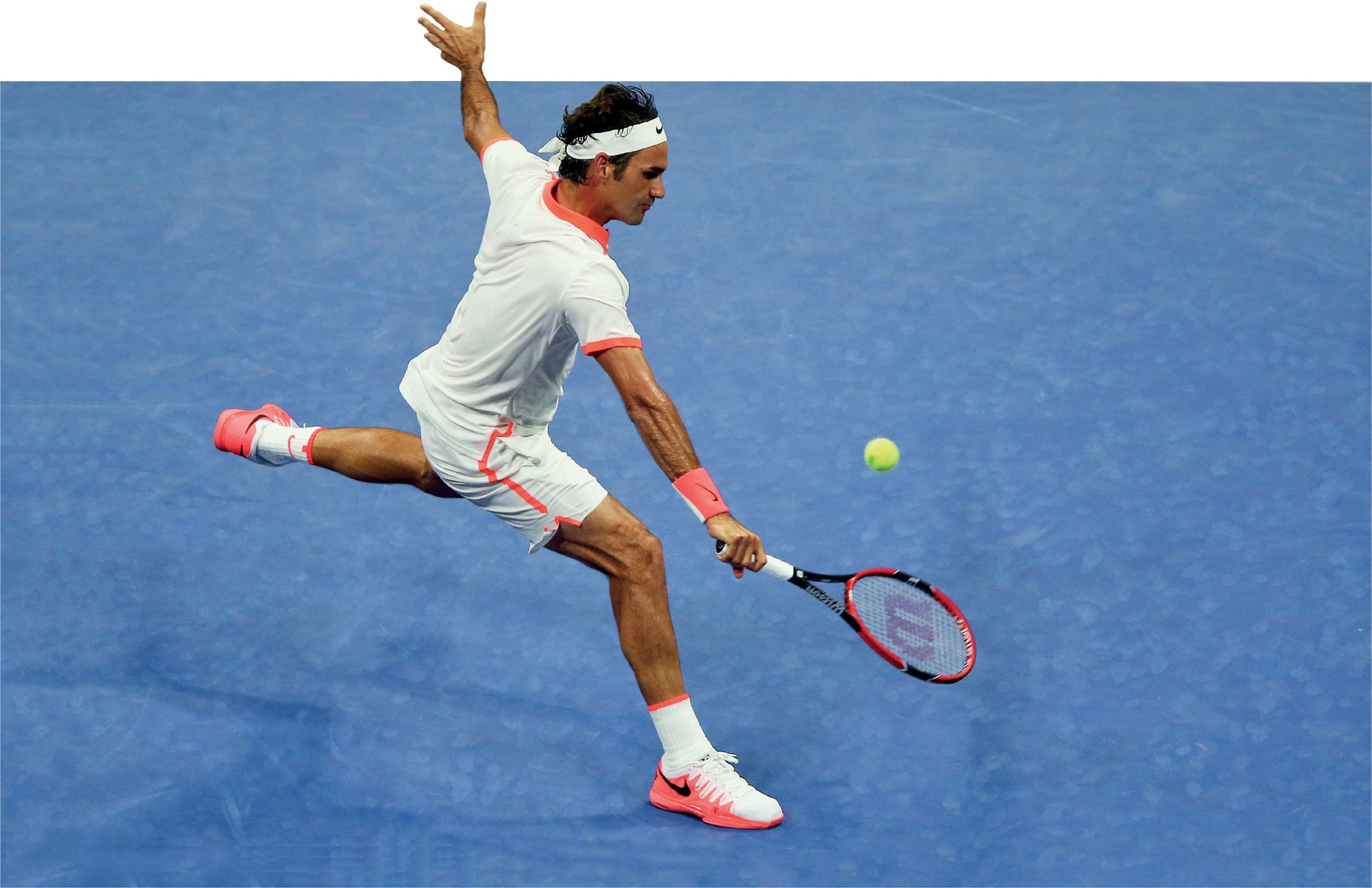

His mind and body were slow and fuzzy with jet-lag, having only just flown in from Europe for a Masters-level event that would be his first tournament in a month his first since the 2015 Wimbledon Championships. Federer wanted nothing more than to cut short practice at the Lindner Family Tennis Center. His French partner, Benot Paire, bothered by an ear infection, also had no great interest in continuing. It was Federers assistant coach, Severin Lthi, standing outside the tramlines, who talked the pair into extending the session by a few minutes. Play a few games, Lthi suggested, knowing that every moment spent on court would accelerate Federers adjustment to the heat and the concrete. Federer consented, but said he would be keeping the points as short as possible and would be kidding around. In other words, it would take the form of rushing in to play half-volley returns when just short of the service-line. These were the circumstances, unlikely as they seem, in which Federer created what he would come to call Sneak Attack by Roger, S.A.B.R. for short, or Fed Attack. But naming his invention was not as important as what the shot signified: that Federer, just days after turning thirty-four, was willing to refresh his game. And to refresh it with just about the boldest, most innovative approach imaginable, with a shot that risked making him look a fool. More than that, it was on this court beside Interstate 71 geographically, culturally, stylistically a long way from the Grand Slam cities of Melbourne, Paris, London and New York that Federer demonstrated his continuing love for tennis.

For years, Federers game has been the closest thing that tennis has come to performance art, and perhaps never more so than when he is playing through-the-legs tweeners at the U.S. Opens Arthur Ashe Stadium. Even now, the tennis salon still debates which was the most spectacular of his New York tweeners or hot-dogs. Was it the one that brought up match point in his 2009 semi-final against Novak Djokovic? Or maybe the one he played against an unseeded opponent in an early round the following summer? But it should not be forgotten that he played those low-percentage shots because, having been lobbed and with no time to track back and hit a regular stroke, there was frankly no alternative. It was low percentage or nothing. With the Sneak Attack, created and developed ahead of that summers U.S. Open, Federer had a clear choice. One was to go with the safe and conventional, and play his return from the baseline. The other ignored all the old orthodoxies of how you are supposed to behave when receiving serve. As his opponent tossed up the ball, Federer would start the charge towards the service-line, and after half-volleying the return, would continue into the net to hit a volley, if one presented itself. He was embracing risk when there was no need to be so audacious. Hence the thrill, hence the fun.

The first couple of times Federer deployed the shot during that practice with Paire, and produced a couple of half-volley winners, he laughed. Paire laughed, too. So did Lthi. The tiredness was forgotten. When Federer left the court he thought to himself how absurd those half-volleys had been. So the next time he practised, he played the shot again, and once again it was a success. To Federers mind, executing this shot really did not seem so hard.

What was innovative, though, was taking the shot from training to competition. Well, Lthi said to Federer, what about using it in a match? To which Federer replied: Really? Yes, really. Lthi was serious. He told Federer not to be afraid of using S.A.B.R. in the big moments. So Federer resolved to be super-sneaky when the stadium was full, and when the cameras were rolling. The possibility of embarrassment, of looking silly, was real. Hit a winner with this shot, Federer thought, and it looked ridiculous. Miss, and it would be even more so. At Wimbledon that summer Federer had finished runner-up to Novak Djokovic. But it was a tournament that is best remembered for what happened a round earlier, in his semi-final against Andy Murray, when Federer turned in his best serving performance for years. Still, for all the praise he received for the way he served that day, and rightly so, that was classic Federer, just Roger being classy Roger, and no surprises. We knew he could serve like that, it was just that we had not seen it in years. This business of hitting half-volley returns, and throwing the server totally off his rhythm, now that was something completely new.

In Cincinnati, Federers opponents and they included Murray and Djokovic were not entirely sure how to take the new tactic. What Federer discovered that week, as he poked and slashed away with S.A.B.R. on the way to winning the title, was that by playing a half-volley return early in the match, it had his opponent forever wondering whether he was going to do it again. On Federers side of the net it also ensured he would play committed tennis. Use the shot without conviction, Federer told himself, and I am going to lose every single point. What had started as a joke had developed into a weapon, and encapsulated much of what made Federer the greatest tennis player in history: the ambition, the desire to attack, the verve, the creativity, and, above all, the talent to do things that others would not even have considered. As became clear a few days later at the U.S. Open, this was a shot that did not just disturb Federers contemporaries, but past generations, too. Djokovics coach, Boris Becker, called the attack almost disrespectful. Had Federer tried such an approach in the 1980s, Becker said, he would have drilled a body-shot at the Swiss. John McEnroe, meanwhile, thought the attack was insulting for what it said about an adversarys serve. During the fortnight at Flushing Meadows people spoke of little else but Federers creation, to what seemed like the displeasure of the Djokovic camp. Over-valued, Becker said of the S.A.B.R., a comment which indicated just why the shot was worth so much to Federer.