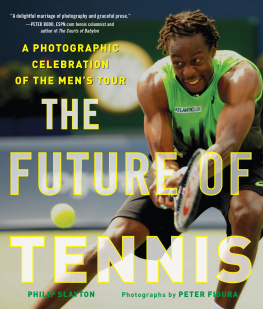

Copyright 2018 by Philip Slayton and Peter Figura

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com .

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

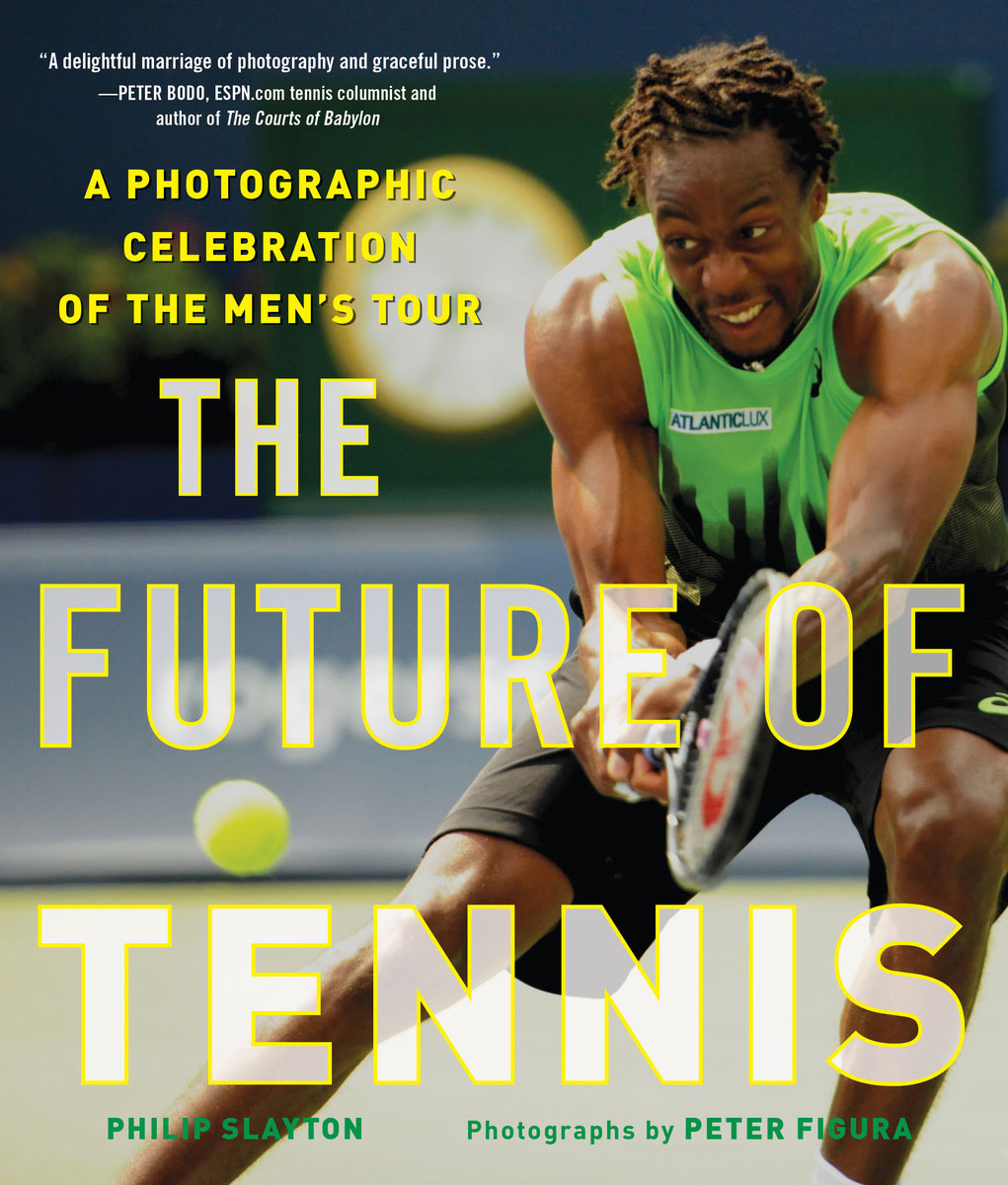

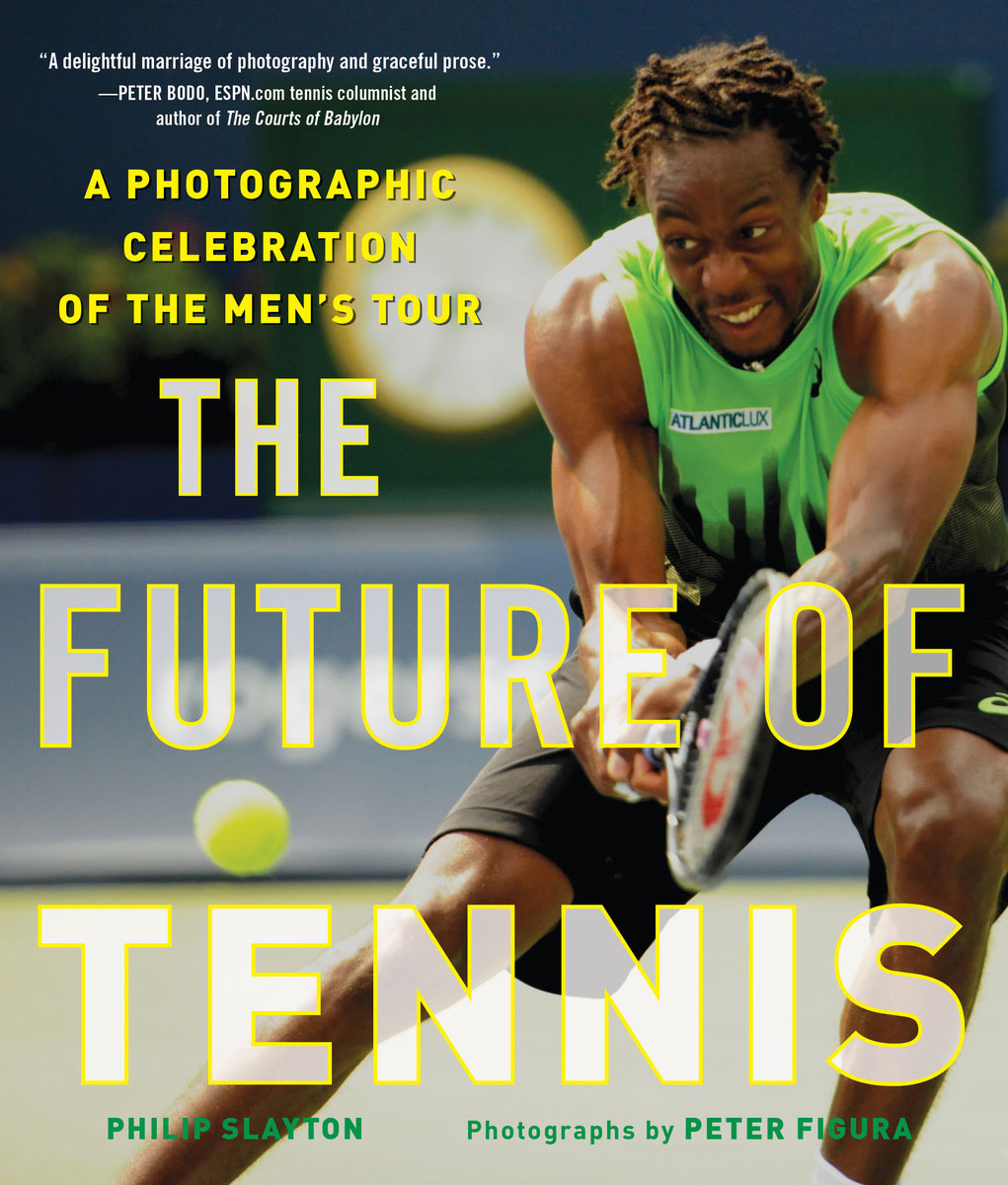

Cover design by Tom Lau

Front and back cover photo credit Peter Figura

ISBN: 978-1-5107-2745-8

Ebook ISBN 978-1-5107-2746-5

Printed in China

TABLE OF CONTENTS

(by Peter Figura)

(by Peter Figura)

(by Peter Figura)

(by Peter Figura)

(by Peter Figura)

THE FUTURE OF TENNIS

Just you and me, baby.Pancho Segura

E verybody who goes to Africa knows about the Big Five game animalsthe lion, leopard, rhinoceros, elephant, and Cape buffalo. Everybody who has an interest in mens professional tennis knows about the Big FourFederer, Nadal, Djokovic, and Murray (some add Wawrinka to this group, conveniently making it the Big Five as well). The Big Five have ruled the African veldt forever. The Big Four (or Five) have dominated mens professional tennis for years. But all the time there have been other players, some with great talent and personality. Who are these athletes, playing in the shadows? Which ones challenge the Big Four today? Who among them will, tomorrow, replace the champions who reign today?

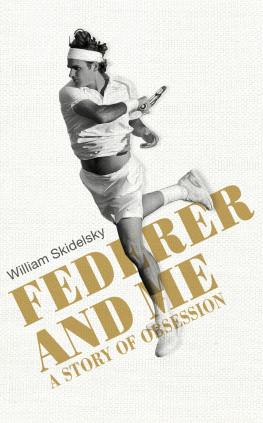

In 2016, change seemed to be in the air. Roger Federer, perhaps the greatest tennis player ever, was turning thirty-five that yearhardly old in the grand scheme of things, but certainly considered up there in the world of professional tennis. Furthermore, Federer hadnt won a Grand Slam since Wimbledon in 2012. Federers great rival, Rafael Nadal, was heading in the same direction: he was born in 1986 and had last won a Grand Slam at Roland Garros in 2014 (and Roland Garros was a special case; after all, the French Open virtually belonged to Nadal). Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray? Also getting old for tennis players, and they were late bloomers, racked by injuries, and had become erratic performers. The days of the Big Four, trading the world No.1 ranking back and forth, slapping each other on the back in the locker room, were surely almost over.

In 2017, the seemingly inevitable unfolding of events was delayed. Roger Federer won the Australian Open and Wimbledon (and then went on to win the Australian Open in January 2018as journalist Kevin Mitchell put it in the Guardian, rejuvenated yet again in the twilight of his career). Nadal won Roland Garros and the US Open. As 2017 drew to a close, Nadal was ranked No. 1 and Federer was ranked No. 2. At the end of 2017, journalist Zac Elkin commented, Another season of tennis has come and gone and so has another unanswered call for the younger generation to snatch the sport from the grasp of the old masters. But the tennis world wasnt completely static in 2017: by the end of the year, Djokovic had sunk to No. 12, and Andy Murray was at No. 16, his lowest ranking since 2008. Both players, hobbled by injuries, missed tournament after tournament, or were defeated early on, or retired from matches. The Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) finalists in November 2017 were not Federer and Nadal, nor Murray and Djokovic, but Gregor Dimitrov and David Goffin, both virtually unknown a short time before (Dimitrov won). Mitchell wrote in the Guardian in early 2018, The old order looks very much in a state of meltdown. The challengers were moving to the fore.

Who among the challengers would eventually replace the old order, when the time inevitably came? Would the new giants of the game come from the stalwarts, those who had been beating loudly and insistently at the Big Four door for some timeplayers like Stan Wawrinka, Juan Martn del Potro, Gal Monfils, Kei Nishikori, Milos Raonic, Grigor Dimitrov, Jack Sock, and Marin ili? Or would they come from the brash, those preternaturally gifted at the game, picked for greatness by some, but burdened by a bad temperamentthe likes of Fabio Fognini, Ernests Gulbis, Nick Kyrgios, and Bernard Tomic? Or from the kids, who had seemingly come out of nowhere and likely had a long career ahead of themDavid Goffin, Dominic Thiem, Sascha Zverev, and Denis Shapovalov? And how to measure and understand these contenders? Could it be done by comparing them to the senior statesmen of the game, whose long careers have come to an end, players like Tommy Haas and Daniel Nestor?

Old Guard versus New Guard: Djokovic loses to Thiem at Roland Garros 2017.

Mens professional tennis is a lonely game and a hard game. A player who aims for the top faces great obstacles and he faces them by himselfphysical and psychological demands, endless travel, financial pressure, intense scrutiny from fans and critics, and an irrational system. The great champion Pancho Segura, who came from an impoverished Ecuadorian background, once described tennis this way: Its a great test of democracy in action. Just you and me, baby. Doesnt matter how much you have, or who your dad is, or if you went to Harvard or Yale or whatever. Just you and me.

In many cases, tennis contenders are young people with little life experience and poor education. Almost all their time from an early age has been spent practicing and playing tennis and traveling the world. The brutal ATP schedule, with its mandatory playing requirements (for example, in most circumstances Top 30 players must in a year play all nine Masters 1000 singles events and at least four Masters 500 tournaments), offers little time for rest and requires incessant travel. The season starts at the beginning of January and ends with the Davis Cup finals at the end of the year. Elite players, those at the very top of the rankings, have entourages (coaches, hitting partners, dietitians, fitness trainers, physiotherapists, business managers, agents), the use of private jets, and luxurious accommodation, to help them along the way and lessen the pain. They have huge incomes. At the end of 2017, Rafael Nadals earnings over his sixteen-year career were $91 million (this is prize money only, and does not include endorsements, which have been estimated to be worth as much as $50 million a year). But the rest, those who aspire to greatness but will likely end up as also-rans, travel economy class, generally by themselves or perhaps with a single coach, stay in motels, and typically have incomes of less than $100,000 a year.

And then theres ranking. The complicated and strict Emirates ATP rankings system is described by the ATP as a historical objective merit-based method used for determining entry and seeding in all tournaments. It is extraordinarily demanding, oppressive even. The system has players constantly seeking new points to increase their playing opportunities and trying to protect points they already have by doing at least as well in any week as they did in the same week the year before. Filip Bondy wrote in

Next page