Copyright 2009 by L. Jon Wertheim

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

www.hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wertheim, L. Jon.

Strokes of genius : Federer, Nadal, and the greatest

match ever played / L. Jon Wertheim.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-547-23280-5

1. Wimbledon Championships. 2. Federer, Roger, 1981 3. Nadal, Rafael, 1986 I. Title.

GV 999. W 47 2009

796.34209421'2dc22 2009005595

Book design by Melissa Lotfy

Printed in the United States of America

DOC 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Judith Wertheim

and Lilly Barr

Introduction

I F ATHLETIC RIVALS aren't outright enemies, they areby definitionadversaries. They fight each other and race each other and try to hit tennis balls past each other. In the most textured cases, they represent different styles and sensibilities and values and heritages. More often than not, there is at least a touch of dislike between them. All that competition, all that comparison, all that familiarity? Hell, yes, it can breed contempt.

But there's also a certain closeness. Bracketed together as they are, most rivals have the good sense to know that, finally, they are better for the existence of their nemesis. Sure, Nicklaus deprived Palmer of a bunch of trophies, just as Magic robbed Bird of a few more NBA titles. And vice versa. But they also pushed each other to greater heights. Sure, chess masters Boris Spassky and Bobby Fischer laid bare each other's imperfections and weaknesses that they would not have wanted to be exposed. But they also forced each other to improve and innovate. Sure, Frazier could have done without getting his face resculpted by Ali. But they also gave each other's achievements some context, some heft. In the end, rivals end up becoming intertwined: Well, we know Ali was good because he beat Frazier, who was so good that he beat Ali.

The peculiar dimensions of rivalry, the necessary distance and the necessary proximity, are laid bare in tennis. Positioned on opposite sides of the net, rivals spend hours engaged in wordless debate, swapping points and counterpoints and clever rejoinders, probing for weaknesses and setting traps. They're out there alone, cordoned off from outside influence. Unlike boxing, there are no cornermen plying them with Vaseline, encouragement, and instruction during breaks in the action. Unlike golf, the competition is simultaneous. A tennis player can't walk down the fairway while his rival takes his backswing. Truly, tennis is the most gladiatorial sport going.

At the same time, there's the built-in collegiality. Tennis rivals may face off a half-dozen times a year or more. They're forever running into each other in this Cincinnati hotel lobby or that Monte Carlo restaurant. They play on the same tour and often share the same management team and shoe sponsor. And sandwiched between all that on-court competition? Before the match, players spend ten minutes warming up together. (For kicks, try to analogize this to other sports: "Hey Joe, before we start to box in earnest, mind if I whap you a few times with my left hand?" "Sure, Muhammad.") And the instant the contest ends, tennis players head to the net for the ritual handshake.

This intimacy, forced as it may be, is particularly pronounced at Wimbledon. At the All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, the top playersmost of the highest seeds and former championsshare a locker room separate from the rank and file. It's not unlike one of those plush, fresh-smelling lounges at the airport, dividing the elite first-class fliers from the great unwashed in coach. Tastefully appointed with birch lockers and high-definition TVs on the walls, this enclave is not much bigger than your average living room. A player sneezes or belches and the others in the room know it. It's here that the top players gather when they're not on the court. High school wrestlers, junior college fencers, intramural soccer players, they wouldn't imagine sharing a locker room with their opponents. Yet at Wimbledon players get dressed alongside the same counterparts whom they'll engage in combat later in the afternoon.

So it was that at 13:00 Greenwich Mean Time on July 6, 2008, an hour or so before they were to face each other in the 122nd Wimbledon finalthe most important match of the year's most important tournamentSwitzerland's Roger Federer and Spain's Rafael Nadal came face to face. Federer was sitting in front of his usual locker, No. 66, relaxing on a pine bench, when Nadal trudged in and headed for locker 101 maybe a dozen paces away. Inasmuch as one man considered the other an interloper or a space invaderthe groom spying the bride in advance of the wedding ceremonythey suppressed any outrage. Federer smiled wryly as if to say, "So, I guess we meet again." He looked genial and unthreatening. Nadal nodded in response, neither coldly nor warmly. Then each went back to pretending he had the room to himself.

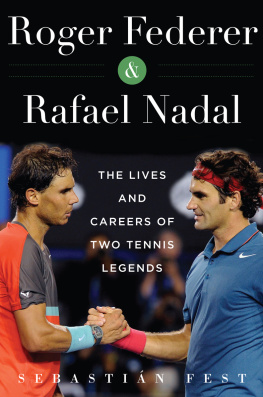

Federer and Nadal form the most dynamic rivalry, not just in tennis but in all of contemporary sport. Together they have created a firewall, dividing themselves from the rest of the field. One or the other had won fourteen of the last sixteen Major Championships. For more than a century, no two men had played each other in both the French Open and the Wimbledon finals in the same year; Nadal and Federer had done it three years running. The 2008 Wimbledon final marked their eighteenth encounter. At the time, Nadal led the head-to-head face-offs eleven to six, including all three matches they'd played previously that yearthough it should be noted that most of the matches were fought on his preferred surface of clay. Four Sundays earlier, Nadal had pasted Federer in the French Open final in Paris. The victory was so comprehensive (scoreline: 61, 63, 60) and so unworthy of their rivalry that it embarrassed both players. Nadal tried to avoid going into the locker room afterward, lest he glimpse Federer. Immediately after the match, Federer wore a brave face in public, but within days he would characterize the defeat as "brutal." Nadal's analysis was more charitable: "I played an almost perfect match and Roger made more mistakes than he usually does."

Yet Nadal was still consigned to No. 2 in the rankings, Federer having inhabited the top spot for 230 straight weeks and counting, a tennis record. What's more, Federer had beaten Nadal in the previous two Wimbledon finalsthe 2007 edition was a five-set insta-classic. The loss had driven Nadal to tears and left him to wonder if he had squandered his best opportunity to win the one title he coveted most.

Beyond the records, their rivalry was heightened by clashing styles. One could spend hours playing the compare-and-contrast game. Federer versus Nadal embodies righty versus lefty. Classic technique versus ultramodern. Feline light versus taurine heavy. Middle European restraint and quiet meticulousness versus Iberian bravado and passion. Dignified power versus an unapologetic, whoomphing brutality. Zeus versus Hercules. Relentless genius versus unbending will. Polish versus grit. Metrosexuality versus hypermuscular hypermasculinity. A multitongued citizen of the world versus an unabashedly provincial homebody. A private-jet flier versus a steerage passenger. A Mercedes driver versus a Kia driver.

The tennis salon's comparison of Federer's evolved beauty with Nadal's Neanderthal drudge is as unfair as it is crass. You can accept the premise that they're both artists even though they're of decidedly different schools. Federer is a delicate, brush-stroking impressionist, and Nadal is a dogged, freewheeling abstract expressionist.

Next page