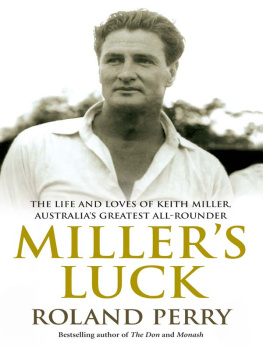

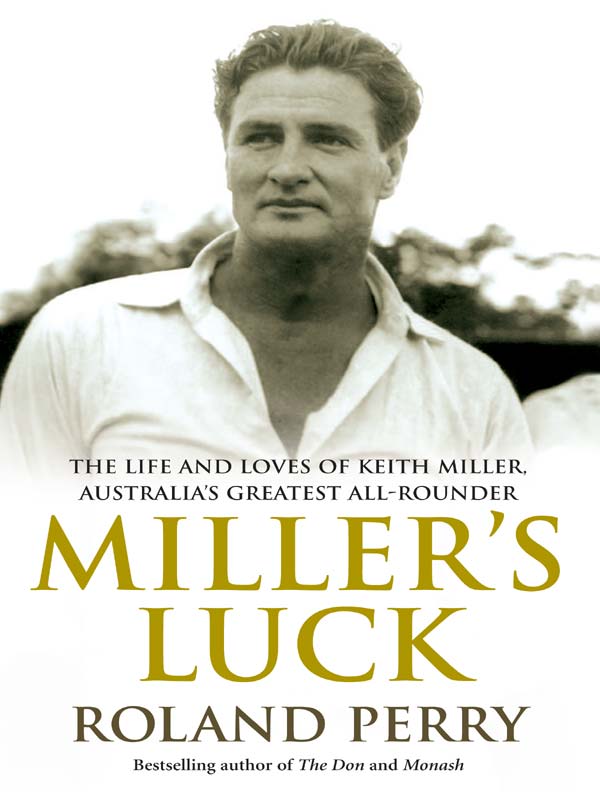

About the Book

In summer 1945 a free-hitting, cavalier Australian batsman and menacing fast-bowler took Britain by storm. With his film-star good looks and athletic prowess, Keith Miller quickly earned the adoration of English fans and the elite alike. His brilliance as a batsman, bowler and fielder ranked him as one of the sports finest all-rounders, but what set him apart was his carefree attitude to sport and life, instilled in him by his experience as an RAF pilot during WWII, when he was in mortal danger daily and saw many friends fall.

Miller could never take sport seriously again. Hero-worshipped wherever he played, Miller was renowned for his generosity and friendliness and never lost his common touch or his rebellious nature; his strong aversion to authority and love of his sport led to spectacular clashes with other cricketing greats.

Bestselling biographer Roland Perry was granted exclusive access to Millers personal archive and conducted extensive interviews with Millers family and closest friends to create Millers Luck , a compelling and intimate account of the fortunate life of Australias most dynamic and charismatic sporting hero.

Keith Miller took two steps down on to the Lords arena. He was greeted by such applause that anyone not knowing he was an Australian would have thought he was English. The date was 27 August 1945. It was the last hour of the second day of a match between England and a Dominions combination, made up of eight Australians, one New Zealander, one South African and one West Indian. Miller was conscious of the fact that W. G. Grace, Victor Trumper, Wally Hammond and Don Bradman had also made those two modest steps for cricket. It gave the tall, lithe and graceful athlete with his characteristic erect back and loose limbs a thrill to be walking the same walk. Miller loved the spirit at this ground, the epicentre of the cricket world. He had made it his own during the World War II years with brilliant performances. They had seen him compared with all the greats of the game.

Most of the 34,000 people packed into the ground had stayed in the hope of seeing Miller. They were full of expectation as he characteristically tugged at his sleeve, used his teeth to wriggle on his batting gloves, and strode to the wicket with the athletic lope of a man relishing the moment. Male fans were riveted to him as he rolled his broad shoulders and glanced skywards, as if searching for enemy planes and missiles, which he and they had done for several years. Female fans clapped and shrieked as he took off a glove and gave his ample dark locks a smoothing over, like the concert conductors he so admired just before a performance. Miller took block and settled into his upright, classic stance. There was no agitated tap of the bat. There was no need with this batsman. His stillness spelt murderous intent, as did his easy grip. It was in the province of the tail-ender, high up the handle, signalling that at every chance he would attempt to belt the cover off the ball and often send it skyward. Yet Miller was establishing himself as a batsman of the highest order. His readiness for mayhem reflected his character rather than his stroke-making prowess.

The score was 2 for 60 in the Dominions second innings. It led England by 80. A Miller special was needed. Already this summer at Lords he had scores for the RAAF, Australia and now a Dominions side of 105, 1 (run out), 7, 71 not out, 78 not out, 75, 63, 118, 35 not out and 26. In previous seasons he had scored several centuries here. He had just been a clear man-of-the-series in five Victory Tests for Australia against England, which celebrated the end of World War II in Europe. Miller was the runaway favourite player of the English summer and had come to symbolise the best of British life, sport and athleticism. He might have been an antipodean of Scottish descent, but he had served with the Royal Air Force as a pilot in a bomber squadron over enemy skies in Europe. The United Kingdom and Lords had claimed him as their own. The matine idol good looks, ready smile and willingness to engage with the spectators all conspired with his outstanding performances to make him the centre of attention with the bat, the ball, or even just fielding. It was said he could catch swallows in slips.

Miller had every motivation to perform. It would be his last big game at Lords for the summer and his wartime stay in England. Hammond had provided a typically fine century in Englands first innings. Miller had tussled with him for preeminence as a batsman all season, and wished to leave his adopted cricket home with a statement. There was little to lose. If he failed, he would still be ranked as equal to the English great. Miller could deliver a swashbuckling show or go down trying.

He moved on to the front foot against the excellent bowling of Test leg-spinners Doug Wright and Eric Hollies. He was in touch from his first cover drive to the fence the second ball he faced. Miller was a player of moods. His footwork demonstrated his finesse on this day, as each movement brought his head and shoulders over the ball, which at first sight seemed exaggerated until the observer realised that this was the norm. Millers backfoot movement also seemed overdone when, in rare moments, the spinners forced him to retreat. The elbow was erect as if an extension of a very vertical bat. Even this defence was a form of attack. The ball was rebounding through the field.

Miller was lunging at deliveries with full confidence and decisive punch, whether to kill Hollies spin or cover-drive Wright with power and the straightest of bats. Another hint early that he was in form was his late-cutting. The artistry and precision of this fine shot were usually the preserve of shorter players, such as Don Bradman or Denis Compton. Yet the taller Miller was as adept at it as these two fine exponents.

Miller reached 49 in 49 minutes. At that score, he took one step down the wicket and lifted Hollies high and straight. Members in front of the pavilion scattered as the ball cleared the fence and bounced right. Three balls later he repeated the feat. Miller was 61 not out, and the Dominions 3 for 145 at stumps on day two.

He always slept on a few beers before a game, but whatever he had on the night of 27 August, it put him in a plundering mood on the third and final morning of the match. New Zealands dashing little left-hander Martin Donnelly (29) was yorked early by Wright. This brought West Indian Learie Constantine, the Dominions captain, to the wicket. Miller went into overdrive, smashing Hollies and Wright with contempt to all parts of the ground. Hammond had no slip. Every fielder was in the deep, in the hope that this flop-haired belligerent would mistime a stroke and sky a catch. As writer Denzil Batchelor put it: The nearest fieldsman seemed in Mesopotamia, while the farther bodies were pretty well astral.

Miller was in an ebullient mood for the second successive day. He asked umpire Archie Fowler if it were true that no one had cleared the pavilion roof with a hit since Australian Albert Trott had done it playing for Middlesex against Australia in 1899. Correct, Fowler replied. He hit a ball from Monty Noble. It struck a chimney pot and fell to the back of the pavilion.