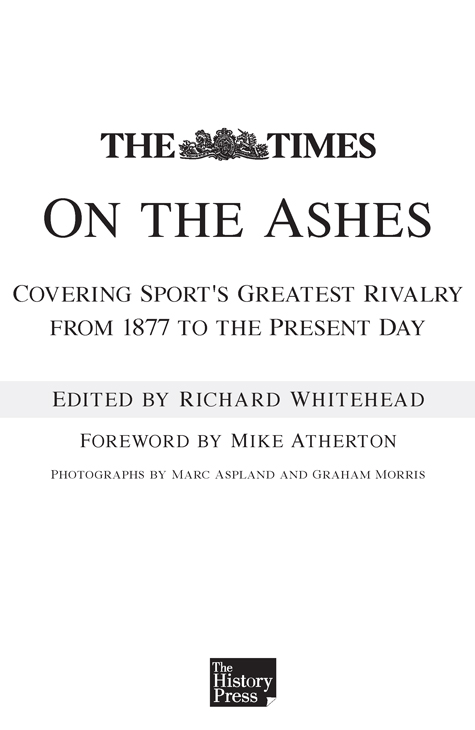

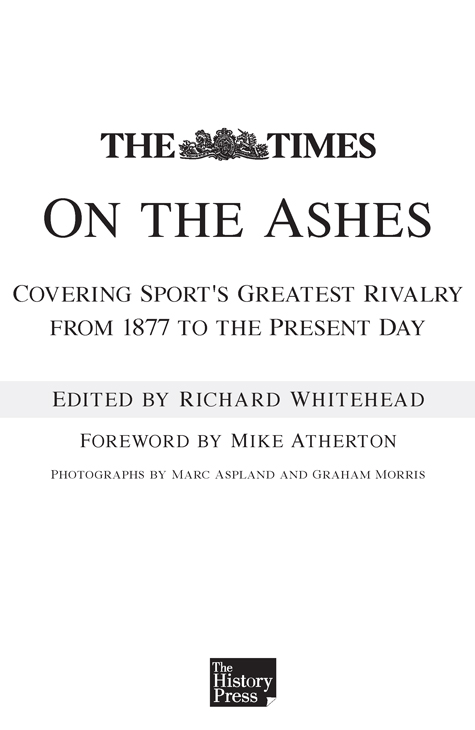

Although only one name appears next to editor in the credits for this book, it was very far from being a solo project. It could not have been completed without the considerable assistance of many others.

Mark Beynon at The History Press was a swift convert to the idea and has been extremely supportive. Thanks are also due to Juanita Hall, the publishers production supremo, and Jemma Cox, the designer, who has done such a wonderful job.

The esteemed cricket photographer Graham Morris showed great generosity in allowing me access to his formidable archive of images, and The Times chief sports photographer Marc Aspland was a huge help. Without their talents this book would look a great deal greyer. Margaret Clark and Ian Whitbread on the picture desk provided vital technical assistance.

Among the writers, Simon Barnes, Tim de Lisle and Gideon Haigh kindly allowed me to use words that were not copyright of The Times .

Nick Mays, TheTimes archivist, and his assistant, Anne Jensen, were magnificent in rooting out the identities of various anonymous cricket contributors, and I cannot give adequate thanks to Dean Burrows for scouring the papers photographic library for many of the wonderful older images. Murray Hedgcock and David Frith kindly helped to identify some of the Australians in those pictures.

Various Times colleagues also gave inestimable help, especially Tim Rice who read the text so thoroughly and with impressive dedication. He was also the first to suggest that the concept might actually work. Walter Gammie, the worlds greatest cricket lover, was helpfully enthusiastic, and gentle encouragement came from Ian Brunskill and Tim Hallissey. Thanks also to my colleagues on the Register.

Christopher Lane at Wisden kindly supplied the photographs of Sydney Pardon and thanks are also due to my former colleague Marcus Williams whose book, Double Century , provided invaluable information on Times cricket correspondents.

But the greatest thanks of all must go to my wife Marion Brinton and son Alex who put up uncomplainingly with my long absences from normal domestic life. I owe them a great debt.

Richard Whitehead

CONTENTS

by Mike Atherton

by Richard Whitehead

by Mike Atherton

B ut now that suddenly a bowler, Larwood, has come into his own, and has dominated the play we find that the full force of attack has returned to its proper place in cricket and at once Test Match cricket has awakened from the sloth of the last 10 years and is again a glorious game so wrote our cricket correspondent about the Bodyline series more than 80 years ago.

Cricket has changed immeasurably since then, but in some ways it has not changed at all. Clearly, our correspondent, reflecting on the events in Sydney in December 1932, was worried about many of the same things that our current cricket correspondent frets over; namely, the long-term health of the five-day game and the precarious eco-system that is the balance between bat and ball, upon which the greatness of the game depends.

For all the cricket correspondents of The Times , named or unnamed atop their copy, this last would be a central concern. We spend our days watching cricket and we all would prefer to watch decent cricket, no matter the result. If that eco-system is out of kilter, if bat dominates ball excessively, or vice versa, then the game is diminished as a result. Cricket writers are, ultimately, only as good as the deeds they describe.

It is this overriding feature the competitiveness of the cricket that has historically set the Ashes apart. Along with its wonderful history and tradition, which gives it prized context, it has more often than not highlighted the best of cricket in all its competitive glory, and occasional goriness.

The practicalities of the job have changed tremendously in the years since Bodyline. John Woodcock, the longest serving and best known, perhaps, of all our correspondents, once told me, with a twinkle in his eye, of his professional commitments on the last tour to Australia that went by boat. A few hundred words at Tilbury Docks, a few hundred more on the stopover in what was then Ceylon, and a few hundred more on arriving in Fremantle. And, of course, a trip to Jermyn Street for a suit on expenses prior to all that.

He played quoits on a daily basis with the England players on the long journey over, he came to know them as friends, socialised with them regularly, so that it was not unusual to find himself in the England changing room from time to time at the invitation of the captain. The players were not paid very much, if at all, and journalists were regarded as their social equals, and probably had much better expense accounts. Very different days, indeed.

The England dressing room is not unknown to me, but I would not dream of entering now without the invitation of captain and coach, which would be unlikely in any event. The dressing room is for players, the press box for cricket writers and very early on in my transition from one to the other, I had to come to terms with the difference. Once you do, it transforms your writing and improves the experience, I would like to think, for our readers. Retain empathy with the players (for the game is immeasurably more difficult to play than to write about), but retain a distance, too, so that you can report and comment without fear or favour.

The distance now between players and reporters, because of the layers of intermediaries such as PR people, agents and press officers, is one of the main disadvantages of modern-day cricket reporting. The daily press conference has actually reduced the power of players words and introduced a level of stiltedness to relationships between writers and players. The other disadvantage is the all-consuming nature of it: the internet means that cricket writers are never out of contact and always within the frame of a deadline. Cricket doesnt sleep any more.

But with the internet has come the ease of actually getting copy from one end of the world to the other. Forty minutes after a match, a thousand words accompanied by the most elegant pictures from our photographers will arrive instantly, allowing readers to download the latest action from Australia on their iPads on the way to work. Radio and television mean that the words do not carry quite the same impact as before, but what impact there is is, at least, immediate.

Nothing comes close to playing in an Ashes series. It stands to reason, then, that nothing comes close to reporting on it. The 2015 series will be the eighth I have covered as an observer, which now means that I have been a professional observer longer than a player (I played in seven Ashes series). A sobering thought. The magic remains, though.

The best series I have ever watched and I think of myself as extraordinarily privileged to have done so was the 2005 Ashes, won by Michael Vaughans team. With England rising and Australia falling, the protagonists were well-matched, the cricket was superb, a star or two (Andrew Flintoff, Kevin Pietersen) was born, the spirit was competitive and hard but fair, and for three matches in August the narrative turned magically this way and that. It was a truly memorable series and represented the very best of the Ashes.

In this book, you can enjoy a trip down memory lane and relive some of those moments, and many more that The Times has brought to you with, we like would to think, accuracy, style and a little flair.

Next page