ON CRICKET

Mike Brearley

CONSTABLE

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by Constable

Copyright Mike Brearley, 2018

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-1-47212-945-1

Constable

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK Company

www.hachette.co.uk

www.littlebrown.co.uk

In memory of Horace and Midge, who set me on this track

and

to Luka, Alia and Maia, who will find their own paths

CONTENTS

In 1964, I opened the batting with Geoffrey Boycott at Salisbury, as Harare was then called, in the first match of the MCC tour of South Africa. We were both young hopefuls, though as things quickly panned out, my hopes were less firmly grounded than his. The game was a two-day friendly match. The pavilion was at mid-wicket in relation to the pitch. Geoffrey and I were each 20 or so not out in the fifty minutes batting we had before tea. He played the last ball and marched off towards the pavilion without waiting for me to join him. I had to run a few paces to catch up with him. I said, cheerfully I think, but perhaps also sarcastically, Are we going to the same place? He turned on me, snapping, None of your egghead intellectual stuff. The name egghead stuck, at least for a while, though I dont think of myself as an intellectual, let alone as an egghead.

Looking back, its tempting to see outcomes in matches and careers as inevitable and to read events and people as simpler than they are and more sharply edged Perth rather than Mumbai. In life we nose our way forwards, uncertain about the future, and indeed with only vague and patchy knowledge of the present and the past.

One of the benefits of becoming an expert (of a kind) in one sphere, however narrow the sphere might be, is that we are in a position to know how little we understand of other spheres (or polyhedrons for that matter). Its hard to really look and see. We are hindered by partial viewpoints, by the complexity of events; by lack of thought, and by over-thinking. (Expectation gets in the way of seeing; as the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein said: Dont think, look; and it is necessary to attempt to suspend and question some of our assumptions if we are to see what is in front of us.)

As I wrote in my book On Form , I think that writing, like playing cricket, like, in fact, many activities of life, involves at best a benign sort of marriage between discipline and spontaneity, between hard work and playfulness, between letting go of conscious control and the application of sometimes critical thought.

What follows is a collection of pieces on the game, portraits of players and issues that have interested me and continue to do so. It is not meant to be exhaustive. There is nothing, for instance, on captaincy, on retirement and depression, or on county cricket. Little on umpiring, on DRS, on grounds, on Middlesex colleagues; even on the future of the game. Some are pieces written originally for newspapers mostly for the Sunday Times, Observer or The Times over the past forty years. I have contextualized, and at least tampered with, them all. Twenty-five are new, or virtually so.

I started this brief pipe-opener with a tiny episode from the tour of South Africa. One continuing area of interest has been race, including apartheid, in cricket (that tour opened my eyes to the horrors of that system and the way it entered every area of peoples lives) and the question of whether it is legitimate to speak of physiological, cultural, racial and social differences in cricketing technique and character. I discuss at some length the DOliveira affair, and some of the personalities involved in that episode (perhaps the most significant in terms of broader influence in life beyond sport of any during my lifetime); the protest by Andy Flower and Henry Olonga at Mugabes Zimbabwe; and C. L. R. Jamess account of the campaign for the election of a black captain (Frank Worrell) of the West Indies team. And I examine some quirks and special skills of the great Indian batsmen, Ranjitsinhji, Pataudi, Sachin Tendulkar and Virat Kohli. Differences of physiology, social customs and personality are to be celebrated and not denied (for reasons of political correctness) or scorned (for reasons of prejudice), but neither are they to be exempt from criticism.

There are many other topics, from John Arlott and Harold Pinter to Alan Knott and Kumar Sangakkara, from being pushed into a rose bush at the cricket ground at Burton upon Trent by an irate Middlesex supporter to conspiring with Philippe Edmonds to put the helmet at short mid-on to tempt Yorkshire batsmen into error in the search for five penalty runs. And there is something on the Ashes including the prediction, almost correct, that Douglas Jardine would win the Ashes but lose a Dominion and on corruption, as in attempts to fix matches or passages of play by Hansie Cronje and by Pakistan players lured by the News of the World sting, as opposed to common-or-garden cheating (including ball tampering).

If a sufficient number of people enjoy the book, and if I live long enough, there may even be a sequel. You may take this as a warning or a promise.

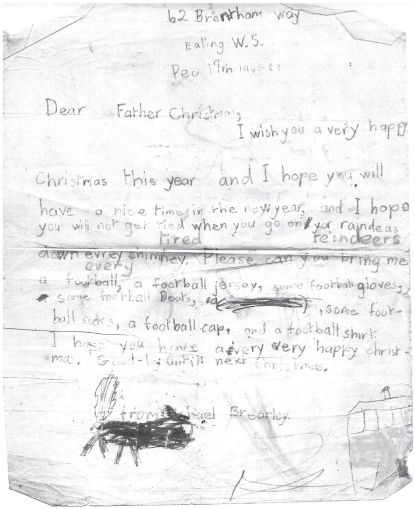

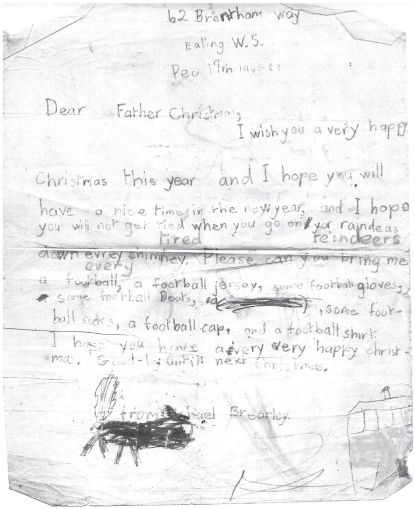

Please can you bring me a football, a football jersey, some football gloves, some football boots, some football socks, a football cap, and a football shirt. Good bye until next Christmas: Extract from letter to Father Christmas, 1948. (I also politely wished him a very happy Christmas and hoped you wont get too tied when you go on your raindeas [sic] down every chimney.)

This six-year-old me, or I, had a one-track mind. Note the football gloves and cap; these were what the Brentham goalie, Paul Swann, wore when facing west late on a winter day. When play was safely down the other end, Paul would chat with this obsessive little boy by his goalpost. Then the players would come sweeping towards his goal, the thud of studs surging like a herd of Father Christmass reindeer, the swirling male bodies barging against each other.

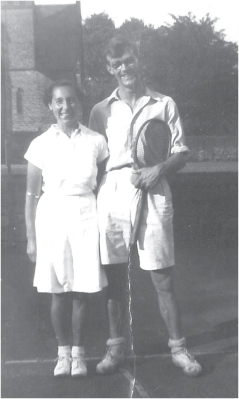

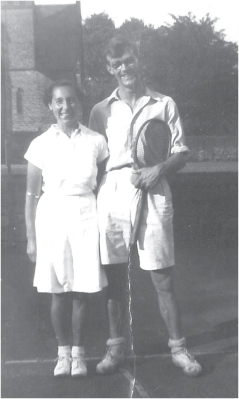

Paul and his brother John were, along with my earthbound father, Horace, my heroes, John particularly. Intermediate in age between my father and myself, he was an excellent footballer and an even better cricketer. He played both games for Brentham, near our home in Ealing, West London, along with my father. He was a capped Middlesex Second XI player, and also played four first-class games for the county between 1949 and 1951.

Smartly turned out, with his upturned collar (did I unconsciously copy him?) John was a correct and classical left-hand batsman, a fine fielder, especially in the covers, and a skilful and reliable leg-spin bowler. He was elegant in everything he did. On the football field I remember him as an athletic, forthright inside-forward.