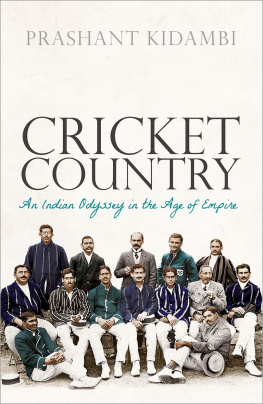

Cricket Country

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Prashant Kidambi 2019

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2019

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019941127

ISBN 9780198843139

ebook ISBN 9780192581112

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

For

Amma, Appa and Roch

Preface

I

The first time a book entitled Cricket Country appeared in print was in the spring of 1944. In celebrating this lost pastoral idyll, Blunden reaffirmed the deeply entrenched view that cricket was truly authentic when it was inviolately English. Tellingly, his book had no subtitle: there could only be one Cricket Country.

Blunden was drawing on a national tradition that had long regarded cricket as uniquely English.

But today even the most ardent English nationalist would concede that there is a new claimant to the title of Blundens book. Cricket, it has famously been said, is an Indian game accidentally discovered by the English.

Few would contest that cricket has become an integral part of Indias raucous public culture, a unifying force in a land riven by myriad cleavages and conflicts. Indeed, for many Indians, their cricket team is the nation. They celebrate its victories as national triumphs, mourn its defeats as national disasters. They regard the Indian team as a symbol of national unity, its social composition as a reflection of the countrys cultural diversity. In this last decade, the respected former cricketer Rahul Dravid noted in a public lecture in 2011, the Indian team represents, more than ever before, the country we come fromof people from vastly different cultures, who speak different languages, follow different religions, belong to different classes.

II

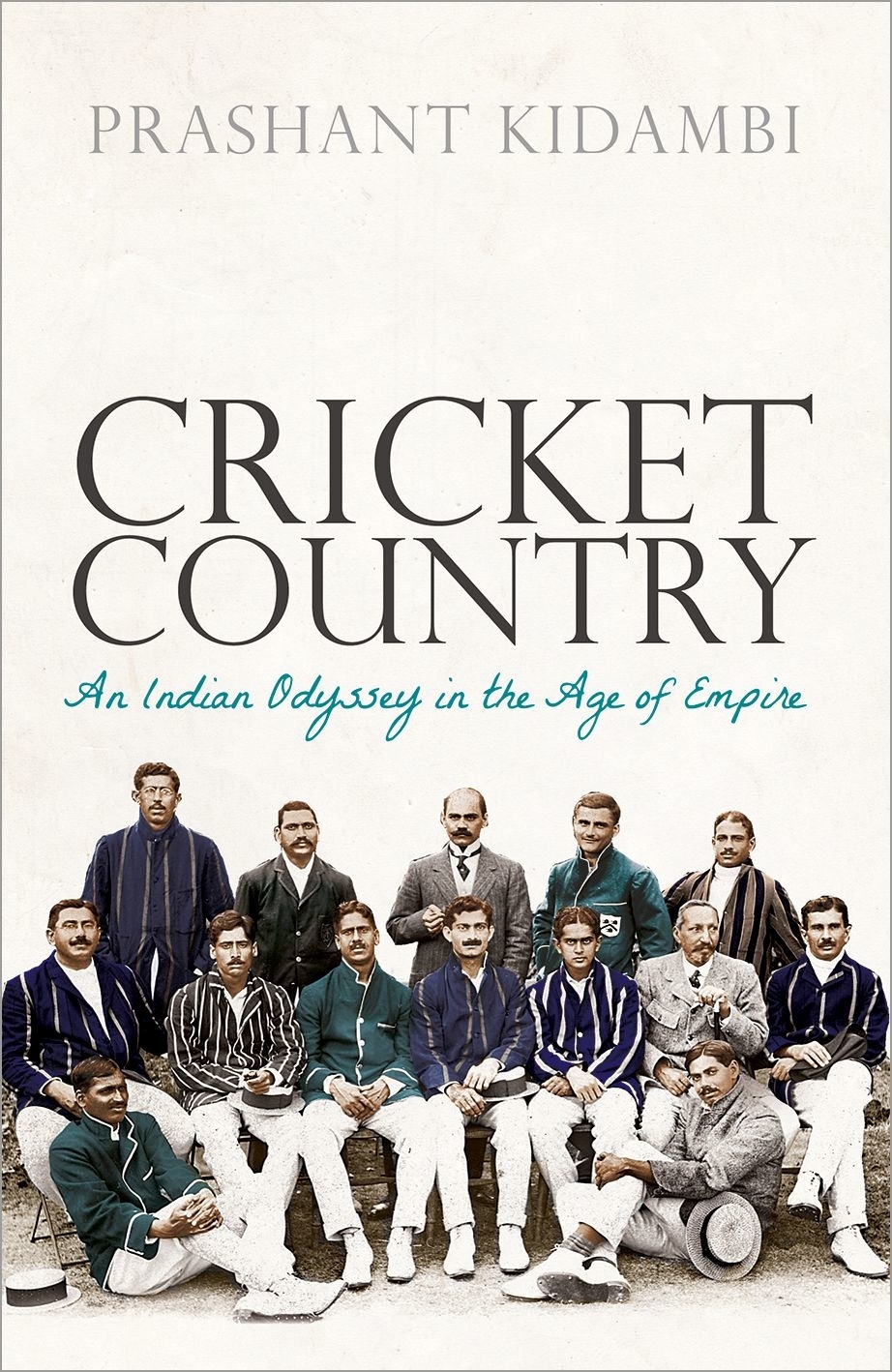

Exactly a century before Dravid uttered these words, the first cricket team to represent India made its debut on the playing fields of imperial Britain. This historic venture featured an improbable cast of characters. The captain of the team was a nineteen-year-old prince, the newly enthroned ruler of the most important Sikh state in colonial India. The other cricketers were drawn from across the subcontinent and chosen on the basis of their religion: there were six Parsis, five Hindus, and three Muslims in the squad that travelled from Bombay to London. Astonishingly, the team included two Dalits, who were deemed untouchable by upper-caste Hindus. Cricket Country is the story of an extraordinary national team and its momentous sporting journey to the heart of empire.

This book charts how the idea of India took shape on the cricket pitch. Principally, it argues that the nation on the cricket field was originally constituted by, and not against, the forces of empire. Drawing on a range of untapped archival sources, the book documents how the project to put together the first national cricket team was pursued by a diverse coalition comprising Indian businessmen, princes, and publicists, working in tandem with British governors, officials, journalists, soldiers, and professional coaches. Because of this transnational alliance, India was represented by a cricket team long before it became independent.

If the attempt to fashion India on the cricket field reveals the workings of empire, Cricket Country also shows how the eventual outcome was decisively shaped by the specific historical contexts within which it was conceived and pursued. The idea of a composite national team was first floated towards the end of the 1890s, when crickets promoters in India sought to capitalize on the stunning rise of Kumar Shri Ranjitsinhji, the Kathiawari prince whose sublime batting bewitched Britain and the wider imperial world. As it transpired, Ranji (as he was popularly known) was loath to participate in a project that might jeopardize his status as an English cricket icon. In the early 1900s, Europeans in colonial India sought to collaborate with powerful local elites in putting together a national team that would showcase the countrys potential as a cricketing destination. Once again, the venture failed; this time because of fierce divisions between Hindus, Parsis, and Muslims over the vexed question of communal representation on the cricket field. A very different set of political circumstances prevailed at the end of the 1900s. The two years between 1907 and 1909 were marked by a wave of violence in which young Indians targeted British officials and their local collaborators. Dismayed by the negative publicity generated by these acts, Bombays leading business magnates and public men, along with prominent Indian princes, sought to revive the project of sending a national cricket team to Britain. Their aim was to use sport to promote a positive image of India and to assure imperial authorities that the country would remain a loyal part of the British Empire.

Each episode in this narrative underscores how the link between cricket and the nation was neither natural nor inevitable. Equally, it highlights how Indian agency, and not simply imperial imperatives, decisively shaped this cricket country.

III

The making of India as a national cricketing entity, then, is the central theme of this book. But local contexts loom large in my account. The story opens in Bombay, the colonial metropolis where the game first struck deep roots in Indian soil. Long before they invested their energies in fashioning a national cricket team, Parsi promoters, publicists, and players had engineered Indias entry into the empire of cricket. The Parsi contests against Europeans in the 1870s, and their tours of Britain in the following decade, laid the foundations of the sporting relationship between colonizers and colonized.

But by 1911, the Parsis were beginning to face a stiff challenge on the cricket field from other Indian communities. Their fiercest rivals were the Hindus, who had come to regard their proficiency in cricket as an index of the communitys social and political advancement. The most noteworthy feature of the Hindu team in the first decade of the twentieth century was the presence in its ranks of the Palwankar brothers, Baloo and Shivram, who overcame entrenched forms of caste discrimination to become the preeminent cricketers of their time. Although they first made their mark in the ancient city of Poona (Pune), it was in modern Bombay that these accomplished Dalit siblings consolidated their formidable sporting reputation.