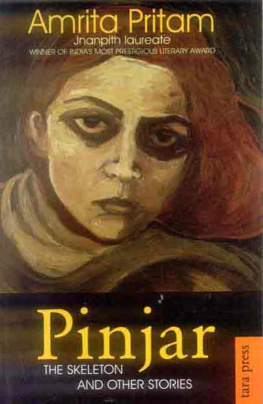

Amrita Sher Gil

A P AINTED L IFE

Copyright Rupa & Co 2002

Text Geeta Doctor 2002

Published in 2002 by

7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj

New Delhi 110 002

Offices at:

15 Bankim Chatterjee Street, Kolkata 700 073

135 South Malaka, Allahabad 211 001

PG Solanki Path, Lamington Road, Mumbai 400 007

36, Kutty Street, Nungambakkam, Chennai 600 034

Surya Shree, B-6, New 66, Shankara Park,

Basavangudi, Bangalore 560 004

3-5-612, Himayat Nagar, Hyderabad 500 029

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Paintings courtesy: The National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi & Photographs of Amrita Sher Gil courtesy: Vivan Sundaram

Cover & Book Design by

Arrt Creations

45 Nehru Apts, Kalkaji, New Delhi 110 019

Printed in India by

Gopsons Papers Ltd.

A-14 Sector 60

Noida 201 301

CONTENTS

C HAPTER O NE

A Sensualist of the Eye

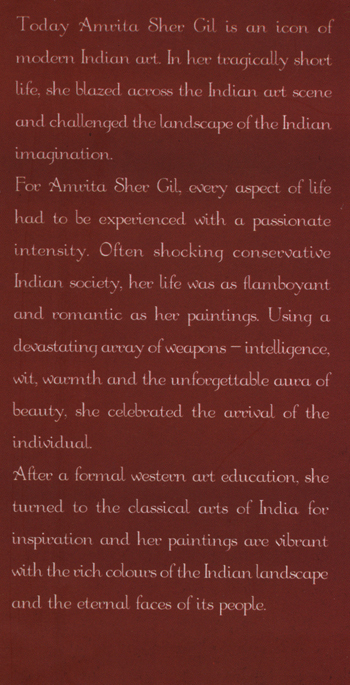

In her life, as in her work, Amrita Sher Gil attracted instant attention. From the moment she stepped into the crowded canvas of the Indian sub-continent in the early 1930s, she sparkled with all the exotic allure of her half Indian-half Hungarian parentage. In a society that was in the grip of the powerful currents of change, struggling to transform the old colonial-feudal order to meet the demands of the 20th century, Amrita leapt gracefully over the breach keeping intact her equilibrium. In her own way using a devastating array of weapons-intelligence, wit, warmth, but most memorable of all the aura of beauty-she celebrated the arrival of the individual. It was accompanied by an ardent search for a more just and egalitarian system of values, particularly in the country that she had decided would be her own canvasIndia. Amrita was able to stamp her own personal quest for self-expression as an artist into an unrelenting search for the soul of the yet unborn nation.

She plunged into the Indian landscape drinking in the colours, with orgiastic glee. "How can one feel the beauty of a form" she asked, "the intensity or the subtlety of colour, the quality of a line unless one is a sensualist of the eyes?"

She reminds one of the American poetess Emily Dickinson, who, filled with the same heightened sensibility, could exclaim: "An inebriate of air am I,/And debauchee of dew,/ Reeling, through endless summer days/ From inns of molten blue." It is as if in recording a moment of pure sensual pleasure, the eye itself becomes drunk, the tongue learns to see and the self dissolves into a dizziness of delicate colours.

Or as Amrita would add, "And art, not excluding religious art has come into being because of sensuality: a sensuality so great it overflows the boundaries of the mere physical."

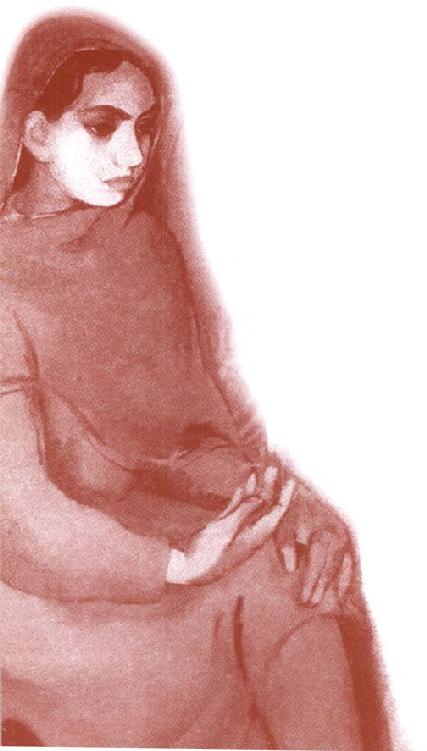

Leaving behind her years of formal education at the Ecole Nationale des Beaux Arts in Paris, Amrita returned to her family estate, near Amritsar in 1934, to begin what was to be her own journey of discovery. She was twenty one years old at the time. No one knew that she had only seven years ahead of her. In that short span of time, she seemed to traverse many worlds. Through her canvasses, she breathed in the Tahitian air of a Paul Gauguin, tasted the apples set on a table by Paul Cezanne, tumbled with the rough peasant contours of Van Gogh's Aries, filling the outlines of her figures with the tenderness of the portraits that she found at Ajanta, while at the same time dipping her feet in the warm waters of the Indian Ocean on her journey to the South of India. She challenged the landscape of the Indian imagination with her men and women who gaze out and away from her canvasses willing us to look at them again, and yet again.

Looking back on her brief, but brilliant trajectory, through the misty dawn of the Indian art world in the thirties, she appears like a small green emerald breasted, hummingbird plundering the nectar from the throat of every brilliant flower that it encounters on its path. Small-boned, bright and bejeweled in brilliant silks and long dangling earrings, Amrita herself would hover just for an instant in the air, before tearing into the heart of yet another lover, another argument, or more importantly, another subject for a painting. She mastered the contradictions that made her the restless creature that she was by transmuting them into the watchful stillness of her luminous compositions. Just as she managed to transcend her dual inheritance as aristocrat and artistic outsider into a triumphant act of ownership that made her, the first, the most celebrated, as also the most fiercely debated of artists, to herald the modern age of art in India.

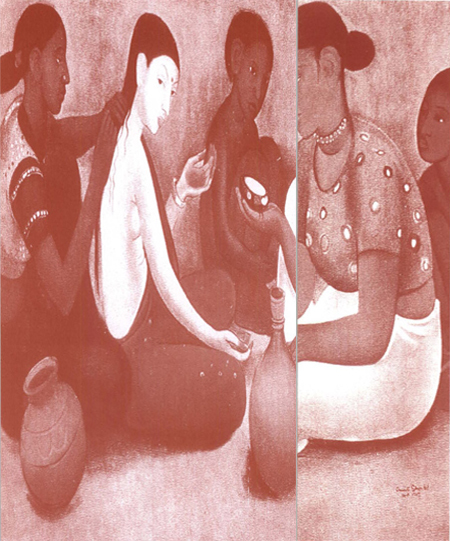

Bride's Toilet. Oil on canvas .

"India belongs only to me!" she declaimed with all the hauteur of the privileged autocrat. At the same time, she also reminded herself that she had a mission, "I am personally trying to be, through the medium of line, colour and design, an interpreter of the life of the people, particularly the life of the poor and sad. But I approach the problem on the more abstract plane of the purely pictorial, not only because I hate cheap emotional appeal and I am not, therefore, a propagandist of the picture that tells a story."

C HAPTER T WO

Hungarian Rhapsody

Even if she had not become the acclaimed artist of modern India, Amrita's life had the romantic quality of a gothic tale, which began long before she appeared on the scene.

Amrita's father, Sardar Umrao Singh Majithia was very much an aristocrat whose family owned large tracts of land, near Amritsar, given to them by Maharaja Ranjit Singh. They had fought bravely on the side of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, against the British. In the next round of battle, the Majithia family fortunes suffered gravely. This time, they found themselves on the losing side, fighting against the British, who took their lands and banished the head of the family to Benaras. During the Great Rebellion of 1857, however, Sardar Umrao Singh's father was loyal to the British. As the head of the Majithia clan he was reinstated and given the title of Raja. He was also awarded a large area of land in the Gorakhpur District of U.P.

After his death, his two young sons were made the wards of the British Government. While the older one inherited the title and was to remain very much a loyalist to the ruling side, Sardar Umrao Singh, after an early arranged marriage and the death of his first wife, went to the London. It was here that he met the young daughters of Maharaja Duleep Singh, the youngest son of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who having been sent into exile, became a part protege of Queen Victoria.

![Geeta [Geeta] Amrita Sher Gil: A Painted Life](/uploads/posts/book/114260/thumbs/geeta-geeta-amrita-sher-gil-a-painted-life.jpg)