Other titles by Colin Wilson available in this series:

RUDOLPH STEINER: The Man and his Vision

G.I.GURDJIEFF: The War Against Sleep

C.G.JUNG: Lord of the Underworld

The Strange Life of P.D.OUSPENSKY

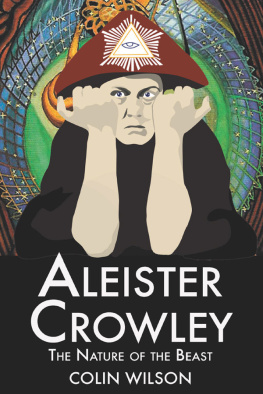

ALEISTER CROWLEY

The Nature of the Beast

by

Colin Wilson

Originally published by The Aquarian Press 1987

This edition published 2005 by

Aeon Books Ltd

London W5

www.aeonbooks.co.uk

Colin Wilson

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A C.I.P. is available for this book from the British Library

ISBN 1 904658 27 X

Printed and bound in Great Britain

Contents

Acknowledgements

THIS BOOK is heavily indebted to many friends: to Israel Regardie, Gerald and Angela Yorke, Roger Staples, Stephen Skinner, Neville Drury, Francis King, Dolores Ashcroft-Nowicki and Robert Turner, all of whom know far more about magic than I do. And, like all the previous writers on Crowley, I owe a major debt to my friend John Symonds; there is a tendency among modern Crowley disciples to denigrate The Great Beast for its attitude of genial scepticism; yet it is hard to imagine how it could ever be replaced as the standard biography. I also owe many insights to the books of Kenneth Grant, particularly to his Typhonian trilogy. Finally, I owe my wife a debt of gratitude for reading and correcting the typescript.

CW

One

Does Magic Work?

I WAS in my early twenties when I first heard the name of Aleister Crowley; it was not long after the publication of John Symonds biography The Great Beast. A friend who had asked the Finchley public library to obtain the book for him was told indignantly that nothing would induce them to spend the ratepayer's money on such vicious rubbish; the library even declined to try and borrow a copy through the inter-loan system. I was intrigued; what had Crowley done that he should be regarded as an untouchable by a London librarian? So when I found a copy in the Holborn library, I read it straight through in a weekend. On the whole, I must admit, I found Crowley irritating; he made me think of Shaw's comment about Mrs Patrick Campbell: an ego like a raging tooth. His life read like a moral fable on the dangers of exhibitionism.

One thing puzzled me: the attitude of the biographer to his subject. Symonds seems to take the sensible view that Crowley's magic was a lot of self-deceiving nonsense. How then should one understand the following passage:

Conjuring up Abra-Melin demons is a ticklish business. Crowley successfully raised themthe lodge and the terrace, [he wrote], soon became peopled with shadowy shapes,but he was unable to control them, for Oriens, Paimon, Ariton, Amaimon and their hundred and eleven servitors escaped from the lodge, entered the house and wrought the following havoc: his coachman, hitherto a teetotaler, fell into delirium tremens; a clairvoyant whom he had brought from London returned there and became a prostitute; his housekeeper, unable to bear the eeriness of the place, vanished, and a madness settled upon one of the workmen employed on the estate and he tried to kill the noble Lord Boleskine [one of Crowley's aliases.] Even the butcher down in the village came in for his quota of bad luck through Crowley's casually jotting down on one of his bills the names of two demons, viz. Elerion and Mabakiel, which mean respectively laughter and lamentation. Conjointly these two words signify unlooked for sorrow suddenly descending upon happiness. In the butcher's case, alas, it was only too true, for while cutting up a joint for a customer he accidentally severed the femoral artery and promptly died.

Symonds tone of light irony implies that he thinks this was all Crowley's imagination; in which case, what really did happen? And what really happened in that Cairo Hotel room on 8 April 1904, when a voice began to speak out of the air, and dictated to Crowley The Book of the Law? Symonds avoids the question with the comment: To enter, however, into the theological side of Crowleyanity is beyond the scope of this biography.

Two or three years later, not long after the publication of my first book The Outsider, I came upon Charles Richard Cammell's book Aleister Crowley, The Man, the Mage, the Poet and, as I read this, I found it hard to believe that he and Symonds were talking about the same man. Cammell came across Crowley's poetry in the early 1930s, and immediately became convinced that Crowley was a poet of genius. When he read Crowley's autobiography, The Confessions, he had no doubt that it deserved to rank with Cellini, Rousseau, and Casanova. In London, Cammell was introduced to Crowleywho was now sixtyand they became friends. The friendship was cemented when Cammell went to dinner and ate one of Crowley's hottest currieswashed down with vodkawithout turning a hair. Crowley had a sadistic sense of humour, and loved nothing more than to see his guests rush to the bathroom to wash down a mouthful of his curry with pints of cold water; when Cammell asked for a second helping and a refill of vodka, Crowley was conqueredHe owned later that I had defeated him over that curry.

Yet Cammell also seems to beg the question of Crowley's magical powers. Describing Crowley's conjuration of the Abra-Melin demons, he also quotes Crowley's own statement that the house became filled with shadowy shapes. But Cammell adds the interesting comment that he believes Crowley's later bad luckhis lifetime of near-poverty and literary failurewas due to his breaking of the sacred oath he took in the Abra-Melin ritualan oath to use his powers only for good and to submit himself to the divine will. To me Crowley appears thenceforth to have been a man accursed: he lost all sense of good and evil, he lost his love, his fortune, his honour, his magical powers, even in large part his poetic genius

Not long after reading Cammell's book I met him at the opening of a painting exhibition in Chelseaa gentle, bearded man who was startled when I told him that I had recently acquired my own copy of his book from New York; he was unaware that it had been pirated. As we stood in the crowd, with glasses in hand, it was difficult to speak seriously about Crowley; but Cammell confirmed that he regarded Crowley as a great misunderstood genius, an outsider, and that he thought Symonds book was little more than a gross libel. Cammell died not long after our meeting, so I had no chance to learn more about Crowley from him at first hand.

In the late 1960s, I wrote my own account of Crowley in a book called The Occult, and a year or two later, entered into correspondence with another Crowley disciple, Francis Israel Regardie. Regardiewho made himself a bad reputation among occultists by publishing the secret rituals of the Golden Dawn societyalso detested the Symonds biography and was not greatly pleased with my own chapter on Crowley. But when I read Regardie's book on Crowley, The Eye in the Triangle, I found it hard to understand his loyalty. Regardie had become a Crowley enthusiast in 1926, at the age of 19, when he read Crowley's classic on yoga Book Four, and wrote to Crowley; the result was an invitation to join Crowley in Paris as his secretary. Within a few monthsas a result of the intervention of Regardie's sisterthey were officially expelled from the country. Regardie finally drifted to London and joined the magical society of the Golden Dawn. After Crowley, he found this insipid and resigned, then hastened the collapse of the society by publishing their rituals. He began to write his own books on magic, heavily influenced by Jung. And when he sent one of these to Crowley, the master replied to the disciple with some sharp criticisms. Regardie admitted later that he should have accepted the rebukes; instead, he wrote Crowley a silly letter beginning:

Next page