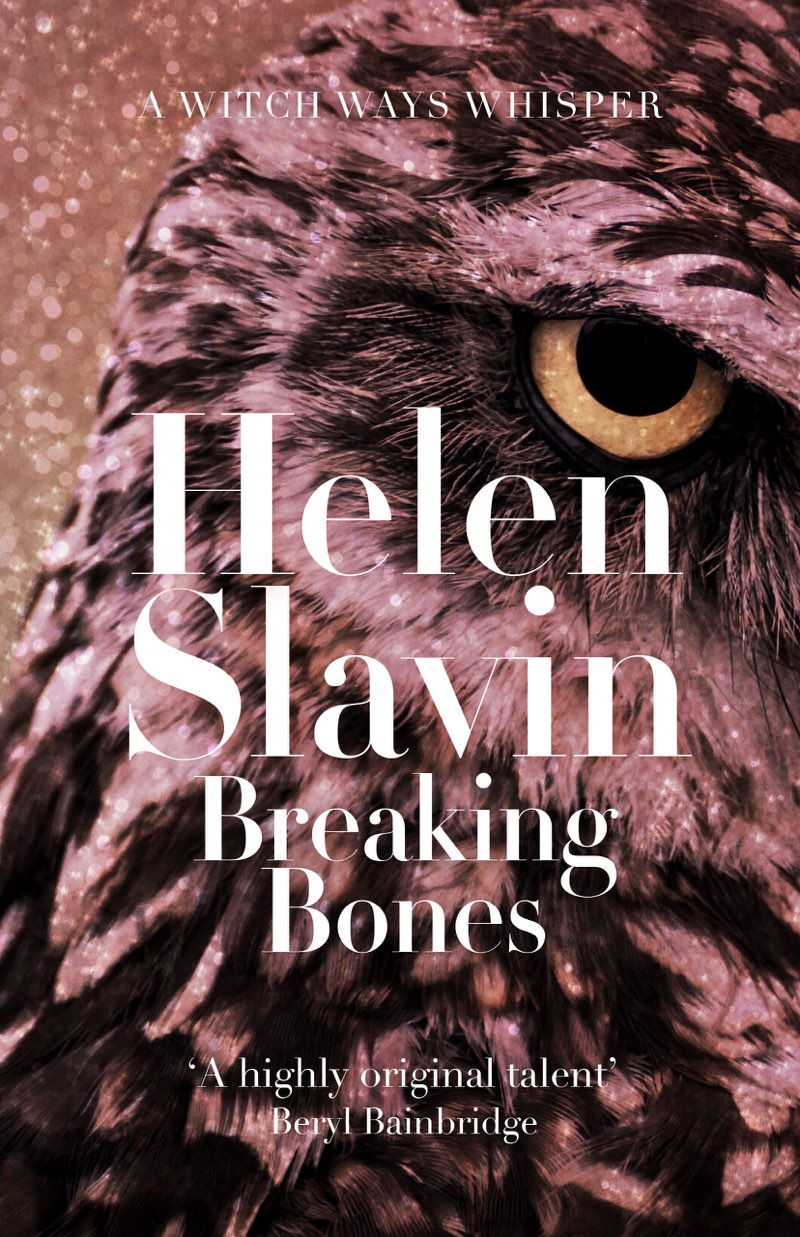

About the Author

Helen Slavin was born in Heywood in Lancashire in 1966. She was raised by eccentric parents on a diet of Laurel and Hardy, William Shakespeare and the Blackpool Illuminations. Educated at her local comp her favourite subjects at school were English and Going Home.

After The University of Warwick she worked in many jobs including, plant and access hire, a local government Education department typing pool, and a vasectomy clinic. A job as a television scriptwriter gave her the opportunity to spend all day drinking tea, living in a made-up fantasy world and getting paid for it (sometimes).

Helen has been a professional writer for fifteen years. Her first novel The Extra Large Medium was chosen as the winner in the Long Barn Books competition run by Susan Hill.

A paragliding Welsh husband and two children distract her and give her ample opportunity to spend all day drinking tea, nagging about homework and washing pants for England. In the wee small hours she still keeps a bijou flat in that fantasy world of writing. When not working with animals and striving for world peace, Helen enjoys the music of Elbow and baking bread. Her favourite colour is purple and if she had to be stranded on a desert island with someone it would be Ray Mears (alright, George Clooney is very good looking but can he make fire with a stick? No. See?)

She now lives, with her family, in Trowbridge, Wiltshire where, when shes not writing, shes asleep. Or in Tesco.

If youd like to hear more from Helen, visit her website, www.helenslavin.com

Twitter

Twitter

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

1

The Path Through the Wood

I n Woodcastle you could hear the primary school bell dinging brightly at hometime. The cool, clear sound would roll off the curtain wall of the castle and ping itself at the bell in the church tower to alert the senses of busy parents and grumpy pensioners. Some hurried to the larder for milk and the oven for biscuits, others rushed to stand at their property boundary ready to wave a curmudgeonly stick at the apple-cheeked happiness that hurtled by.

The schoolchildren would flit out of the school gates and funnel themselves into the small, low-beamed shop Sweeties a brown and sticky emporium on Dark Gate Street, lit by very little daylight through the original dimpled glass windows. The rows of tall clear jars with their bounty of crackling, crunching, chewy delights appealed to every child in the town. To most of the junior population of Woodcastle, the instruction to Eat Your Greens could be twisted into meaning you must munch your way through a bag of sherbet limes or gooseberry sours.

Only one child resisted the jewel-bright, boiled confections. She didnt like them. They were too sticky, too sickly. They had a metallicky aftertaste that was unpleasant because, as she had been told by Mrs Walters, the housekeeper, they were extruded through a machine in a factory outside Castlebury.

Its a big tall place with big tall towers, and big tall plumes of smoke chug out of it every day. Mrs Walters was rubbing her gnarled fingers through a mixing bowl of flour and butter. There was a Kilner jar of caster sugar awaiting its turn along with two speckled-brown eggs that Mrs Walters had asked Winn to fetch from the hencoops. There was cream, too. Revolting stuff for revolting children. They have rats running up and down the belts in that place. My brother knows that for a fact.

Because your brother is a rat-catcher. Winn recalled earlier, more bloodthirsty conversations and the afternoon when Mrs Walters brother had come to Hartfield with his little dog, Whip. She had been allowed to witness the hunt, had admired the skill and speed of the little dog pitted against the rats. Winn harboured a desire to be a rat-catcher when she grew up just so that she might have a little dog exactly like Whip.

The scones, when they were baked, were left to cool on the rack by the windowsill. There was a pot of jam being sourced from the big pantry, and Winn was wrapping a wedge of cheese from the dairy. Mrs Walters made the cheese at Hartfield, and the resulting rich and complex flavour of Hartfield Hard was renowned at the market in town. Mrs Walters made more money from selling cheeses than she did from her actual job as a housekeeper.

This was just as well, because Winns father, Sir Henry Hartley-Hartfield, was miserly. He was miserly with his staff, the entire of Hartfield being run by Mrs Walters. There was a gardener once or twice a week, Mr Vasey. He smoked his pipe in the potting shed as Mrs Walters double-dug trenches for climbing beans. The bulk of the domestic tasks were also assigned to Mrs Walters, who, aside from the cooking and child-rearing, was often to be found pointing walls, replacing ridge tiles, and glazing the orangery. In addition, she could strip down and repair any of the cars and motorbikes in Sir Henrys extensive collection.

He was miserly with his daughter, and this had been a blessing. Winifred had not been sent to boarding school in the family tradition, because Sir Henry did not think she was worth the expenditure. The girl was not pretty and not clever and, with the way the world was going to ruin anyhow, she would be better off learning how to strip down the Enfield and tinker with the plumbing. She was not wife material. It was a fact, and Sir Henry Hartley-Hartfield was a man who dealt in facts.

Her mother had died in childbirth and, if the truth were told, rather than view Winifred as a lasting testament to his stern but deep love for his wife, he viewed the child as an underhanded assassin.

The underhanded assassin was, today, being entrusted with taking a basket of scones and bread rolls, jam and pickles to old Mrs Massey, who lived at the other side of Leap Woods from Hartfield.

Now, what are your instructions? Mrs Walters had folded the spotted teacloth over the top of the basket of provisions and was leaning on the worktop looking very seriously at Winn Hartley-Hartfield.

Twitter

Twitter