**

1.1 Thanksgiving dinner scene, 1937. xii

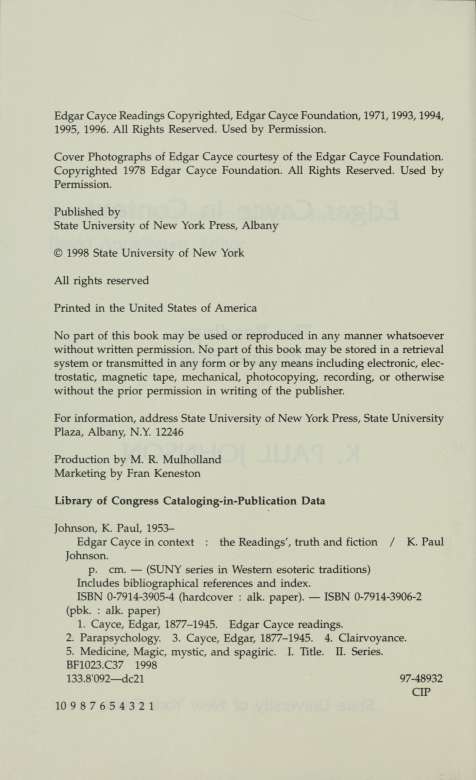

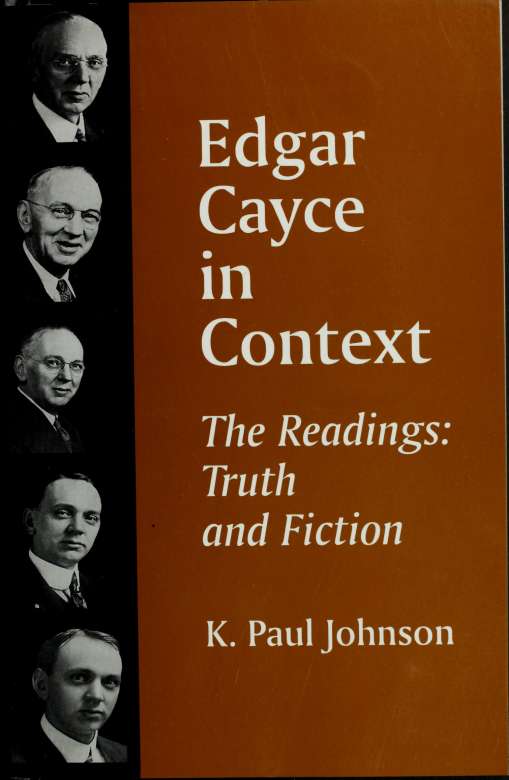

1.1 Edgar Cayce, circa 1910. 12

2.1 Edgar Cayce, early 1920s. 36

3.1 Edgar Cayce, 1932. 60

4.1 Edgar Cayce, circa 1940. 96

Acknowledgments

Many people were very generous with time and interest in this project. Charles Thomas Cayce, David Bell, Harmon Bro, Mark Thurston, David Lane, Kym Smith, and Mary Graham all read the manuscript in full and provided useful advice for revision. Every suggestion made by these readers has been utilized to the best of my ability; remaining weaknesses in the book are my own. Edgar Evans Cayce, Paul and Walene James, Ken Butler, Chris Chandler, Larry Androes, Michael and Brenda Dougherty, and Charlotte Anderson read portions of the manuscript and provided helpful feedback. In conversations with Charles Thomas Cayce, Harmon Bro, David Bell, Paula Fitzgerald, Kirk Nelson, Pamela Van Allen, Grace Knoche, and Kirby Van Mater, I was given useful perspectives on the Edgar Cayce readings. I especially want to thank my cousins Carol Garrison, Doris Agee, Robert Rice, and Patricia Thompson for sharing their memories of Virginia Beach in the 1930s and '40s.

Postmodern readers may wish to know something of an author's biases at the outset, so I offer here a brief disclosure of my background and approach. My intention in this book is to provide a fair, balanced, sympathetic but objective introduction to the readings. In Tidewater Virginia, where I was born and reared, Edgar Cayce is regarded by many locals as an adopted native son. As a child I heard only good things about him; my Virginia Beach cousins had known Cayce as a family friend and remembered him fondly as a kind, unpretentious man who was beloved by the neighborhood children. The first book about him that I read, Edgar Cayce on ESP, was written by my cousin Doris Agee when I was a teenager. I belonged to the A.R.E. for a year in 1977-78 before focusing most of my attention on Theosophy for the next two decades. As an adult I have been influenced by the readings' guidelines on health and meditation, and participated in three Search for God groups at widely-spaced intervals. In 1995 I renewed membership in the A.R.E., but have never been involved in the organization apart from study group participation. Neither an insider nor an outsider, I can perhaps best be described as a "skeptical believer" in Cayce (as in Blavatsky, subject of my previous books). Balancing sympathy with objectivity entails a struggle to keep one's perception of facts uncontaminated by one's appreciation for the person or movement studied. The cost of such ambivalence is finding oneself condemned as too skeptical by believers and too credulous by skeptics. But this can be outweighed by the benefit of seeing possibilities that are unrecognized by partisans on either side of a polarized debate. I am a public librarian without advanced degrees in any academic discipline, and take a generalises approach to the readings. My scholarly specialty is in the history of esoteric and metaphysical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the English-speaking world. To be fully qualified for appraising the Cayce readings, one would need scholarly expertise in medicine, theology, psychology, and parapsychology; as a layman in all these fields I can offer only an overview of the major issues that deserve (and have in some cases received) deeper investigation by more qualified scholars.

It has been encouraging, in the wake of outraged Theosophical reactions to my earlier books, to discover the open-minded, nondefensive attitudes of A.R.E. leaders and authors regarding questions about Cayce's accuracy and sources. Charles Thomas Cayce, Edgar Evans Cayce, Mark Thurston, and Harmon Bro have been generous not just with helpful advice but also in their willingness to consider seriously the positions advanced in the following pages, skeptical or innovative though they may be. On the skeptical side of the equation, David Bell and David Lane have helped to prevent my enthusiasm for Cayce from undermining my objectivity, and have devoted as much time and energy to advising on the manuscript as the A.R.E.-affiliated persons named above.

I thank everyone who has shared in the evolution of this book, including the SUNY Press editors whose care and interest have been a steady encouragement. I thank the Edgar Cayce Foundation for permission to quote from the readings, and Jeanette Thomas for her assistance in this regard. The staff and volunteers of the A.R.E. Library were unfailingly helpful, and I particularly thank Claudeen Cowell and Alan Smith for their assistance.

Thanksgiving dinner scene, 1937. Clockwise from left: Lucille Kahn, Gertrude Cayce, Edgar Cayce, Mary Sugrue, David E. Kahn, S. David Kahn, Hugh Lynn Cayce, Gladys Davis, Thomas Sugrue.

Photograph courtesy of the Edgar Cayce Foundation. Copyrighted 1978 Edgar Cayce Foundation. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

Introduction

Edgar Cayce's life and teachings uncannily recapitulate those of the founders of major American-born religious movements. Like Joseph Smith, prophet of Mormonism, Cayce experienced an angelic visitation in his youth, was recognized as psychically gifted by his family from an early age, and conveyed a new view of history derived from records that only he could see and read. Cayce's Kentucky home was in a region powerfully affected by the revivalism of the early nineteenth century, as was the "burnt-over district" of upstate New York where Mormonism was born. A crucial turning point in Cayce's life was his own miraculous healing that led to a commitment to healing others; in this he parallels Mary Baker Eddy, "discoverer" of Christian Science, whose emphasis on the influence of the mind on health is echoed in the Cayce readings. Like Ellen G. White, chief founder of the Seventh-day Adventists, Cayce combined a Bible-centered world view with a strong emphasis on diet and health; both received their revelations in a trance state and synthesized the alternative health systems of their eras. Cayce restored belief in reincarnation to a Western consciousness that had long since forgotten it; his most important precursor in this role was Theosophy's Madame Blavatsky, whose teachings find many parallels in the Cayce readings. Nevertheless, Cayce has yet to be recognized as a pivotal figure in American religious history as have Smith, White, Eddy, and to a lesser extent Blavatsky. The Association for Research and Enlightenment founded by Cayce and his associates has never promoted an independent religious identity comparable to Mormonism, Christian Science, Adventism, or Theosophy. Instead, it encourages its members of various faiths to remain in their folds while applying the spiritual wisdom and practical guidance found in the Cayce "readings." Cayce's influence has thereby permeated the inchoate milieu known as the New Age Movement, without crystallizing into ecclesiastical forms. Equally distinctive is the fact that virtually all of Cayce's voluminous body of work, which at 49,000 pages far exceeds any of the above-mentioned spiritual leaders, was produced in a trance state of which he denied all memory. Rather than crafting a single message to humanity at large or to his followers, Cayce gave one message ("reading") at a time, more than 14,500 by the end of his life, the great majority to individuals. More than two-thirds of these were medical readings on a wide variety of ailments. Life readings providing spiritual and psychological advice as well as information about previous incarnations account for fourteen percent of the total. Business questions were answered in five percent of the readings, and another four percent gave dream interpretations for individuals. 1 Among the remaining miscellaneous readings were many answering questions from Cayce's co-workers concerning goals and methods of implementing his ideals in organizational form, which are now known as the "work" readings. As a result of the readings' specificity, it has taken years of effort to derive generally applicable principles from the mass of personal advice.

**

**