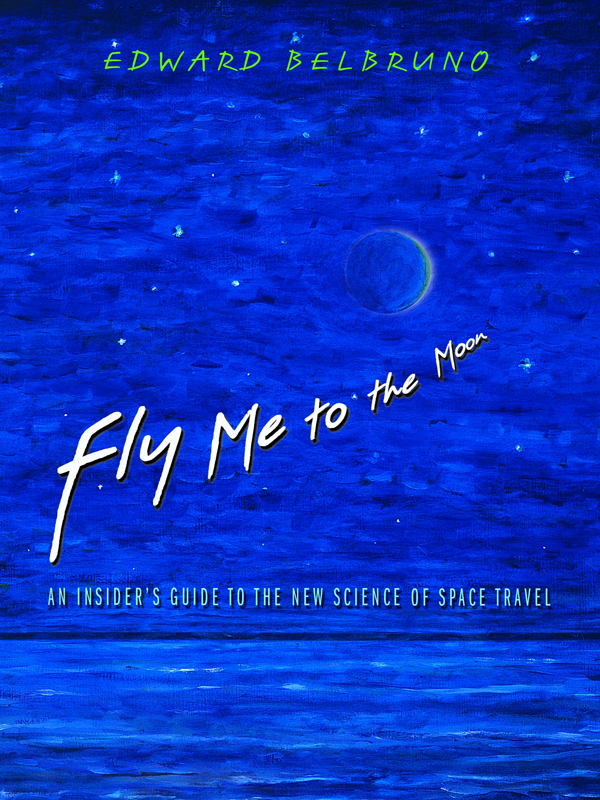

Fly Me to the Moon

Fly Me to the Moon

AN INSIDERS GUIDE TO THE NEW SCIENCE OF SPACE TRAVEL

Edward Belbruno

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2007 by Princeton University

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street, Princeton New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Belbruno, Edward, 1951

Fly me to the moon: an insiders guide to the new science of space travel / Edward Belbruno

p. cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12822-1 (cl : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-12822-7 (cl : alk. paper)

1. Gravity assist (Astrodynamics)Popular works. 2. Celestial mechanicsPopular works. 3. Chaotic behavior in systemsPopular works. 4. Many-body problemPopular works. 5. Outer spaceExplorationPopular works. I. Title.

TL1075.B45 2006

629.4'111dc22 2006043749

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Printed on acid-free paper.

www.pupress.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the exploration of the Universe and to everyone who has helped me in my journey.

Foreword

Neil deGrasse Tyson

Sometimes, history comes fast.

A mere 65 years, 7 months, 3 days, 5 hours, and 43 minutes after Orville Wright left the ground on the first-ever powered flight, Neil Armstrong, the commander of Apollo 11, uttered his first comment from the Lunar surface, Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.

Of course the Wright Brothers 1903 aero plane was heavier than air. Their new fangled machine would be quite useless across the quarter-million-mile airless gap between Earth and the Moon, as would every airplane invented and designed since. So the Apollo missions cannot be considered the natural extension of tinkering with winged craft, even though the lunar module of Apollo 11 was named for a bird.

In the era before heavier-than-air flight, there was lighter-than-air flightback when drifting slowly through Earths atmosphere in the gondola of a hot air balloon was all the rage in the western world. To move effortlessly with the breeze was not enough for Jules Verne, the celebrated visionary and science fiction writer. Instead, he set the Moon in his sights, and knew that such an airless journey precluded the use of balloons and other imagined flying machines of the day. He proposed in his 1865 novel From the Earth to the Moon that this first trip, taken by three men, two dogs, and some chickens, would require a means of moving without the buoyancy of air. And so he loaded his spacefarers into a large bullet-shaped shell, and fired them out of an enormous gun; not unlike the circus performer who gets shot from a cannon to an awaiting net.

Verne badly underestimated the effect on the human body of explosively accelerating from zero miles per hour to Earths escape velocity of seven miles per second. At the rate given, the three Moon voyagers and their animal companions would have become instantly pinned to the rear of the ship, and then crushed by the g forces into a pile of goo.

Carnage notwithstanding, the real message here is that, to Jules Verne and to the readers of his celebrated book, the Moon was not simply a cosmic object hovering at an unreachable distance. The Moon was as destination. The Moon was a world to be explored, with no less curiosity than one might carry to a distant mountain range, or to the far side of the ocean.

Curiosity. Humans have never lived without it. Who knows what thoughts course through the minds of other animals when they look up to the night sky. First, do they look up at all? And if they do, then do they wonder whats up there? Do any of them share our thoughts of adventure, as we stand on Earths surface and feel the call of the cosmos? I doubt it. But even if they did, not only can we dream it, we can do something about it.

No, you cant (or rather, shouldnt) catapult complex living matter such as humans through space inside of oversized bullets fired through humongous cannons. You can, however, send people in rocketsan innovation that would await the creative efforts of American engineer Robert Goddard, who, in the 1920s pioneered liquid fuel propulsion. Upon the success of his rocket, especially the versions where you can throttle the thrust, thereby softening the g-forces on the occupants, Goddard immediately recognized the value of such a discovery for a Moon voyage, but was saddened by what would surely be the prohibitive cost of such a trip, lamenting that, it might cost a million dollars.

Goddard was indeed a better engineer than economist: in modern dollars, thats about the cost of ten hours time of the Space Shuttle in orbit.

Isaac Newtons law of gravity tells us that all cosmic objects pull on you at all times: the Sun, the Moon, Earth, other planets, the stars. And since everybody is in motionin orbit around somebody else-your detailed trajectory through space can, and will be, quite complex. So, perhaps, we should not be surprised that people are still figuring out clever ways to maneuver around the solar system. One of my favorites is the gravitational slingshot. Today, with slim budgets, hardly any space probe has enough fuel to reach its destination without the help of another planets gravity. The Galileo space probe to Jupiter, for example, required a three-planet gravity assist: first Venus, then Earth, and then Earth again, before heading for the outer solar systema move that remains the envy of billiard enthusiasts.

Another of my favorites comes from a web of spooky, interconnected zones among the planets and their moons, where the sum of all forces is small, if not zero. Under these conditions, motion is practically effortless as you drift slowly through space. Barely understood until recently, and hardly explored until the work of Ed Belbruno, these newly discovered interplanetary highways offer a romantic reflection of the pre-rocket, pre-airplane era, where balloons would transport us, with hardly any energy of our own, from one unexplored vista to another.

Preface

Fly me to the Moon, let me play among the stars. Let me see what spring is like on Jupiter and Mars. Thus begins the song made famous by Frank Sinatra. Since the beginning of time, people have been gazing into space and wondering what might be out there. Each decade in recent history has witnessed a major event connected with space. Whether you were glued to your television set in 1969 to watch the first lunar landing, or recently, the Rover mission to Mars, there has long been a fascination with space and space travel. Many of us have wondered if we have neighbors in space or if we will be able to take a vacation to the Moon in our lifetime. Is it even possible? Not only is it possible, it is probable.

In 2004 Princeton University Press published my book Capture Dynamics and Chaotic Motions in Celestial Mechanics: With Applications to the Construction of Low Energy Transfers. After the publication of this technical monograph, I was pleasantly surprised to see the interest on the part of the media, which made a number of requests that I explain the content of the book to the more general reader. After encouragement from my editor, I wrote this little book on how the use of chaos is changing the way we maneuver in space. The 1987 publication of James Gleicks book

Next page