Keene - Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain

Here you can read online Keene - Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Great Britain, year: 2015, publisher: Oxford University Press, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- City:Great Britain

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Keene: author's other books

Who wrote Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp , United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Melanie Keene 2015

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2015

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014950221

ISBN 9780199662654

ebook ISBN 9780191639647

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Here about the beach I wanderd, nourishing a youth sublime

With the fairy-tales of science, and the long result of Time.

Tennyson, Locksley Hall (1835)

My thanks to all at Oxford University Press for their help in seeing this work into print, particularly Latha Menon, Emma Ma, and Jenny Nugee. Thanks to Sophie Basilevich for her help with the images.

Also many thanks for reading and commenting on parts of this manuscript to Jim Secord; members of the History of Science Workshop in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge; Amy Blakeway, Daniel Trocm-Latter, and Alice Wilson at Homerton College, Cambridge; and Marie Besnier. Feedback from audiences at conferences of the British Society for the History of Science, the British Society for Literature and Science, the Cambridge Childrens Literature Seminar, the Oxford History of Childhood Seminar, the Commission for Science and Literature, and participants in an Aberdeen workshop on literature and science was also invaluable.

As ever, I could not have written this book without the love and support of Nick and my family.

We have believed Mr Gradgrind for far too long. When he appeared in 1854, at the beginning of Charles Dickenss novel Hard Times, Thomas Gradgrind embodied everything that was dry and dull in Victorian scientific education. In this way, Dickens brought out the close relationship between facts and fancy that existed throughout the nineteenth century. Scientific education was not just to be had through fusty educational primers: it was also found in wonderland.

Dickenss novelistic intervention was just one part of a wider educational debate ongoing in the mid-nineteenth century around what children should read and do, and in what ways. The rising generation, it was argued, lived in an ever-progressive age, aware of its own innovations and place in history. Novel inventions harnessed the power of steam and electricity; new career opportunities in urban centres and beyond affected societal relationships, working patterns, and more, changing the texture of daily life within Britain, and her Empire across the globe. It was clearas both Parliamentary committees and the pages of Punch, an influential satirical periodical, attestedthat the traditional systems of childrens education must also advance with the age. Everything from elementary instruction to the contents of the toy-chest, Punchs mock-journalist argued, should be reformed, in order that young audiences best be prepared for the modern world. When everything else is moving, it was especially important that provision for children should not remain at a stand-still.). The sciences were to be found at the heart of all of these developments, not only as an emblem of the age, but also as a crucial missing element from the curriculum.

Dickenss opening scene in Hard Times therefore presented a case-study in taking too literally an extreme reliance on what had been termed useful knowledge, intellectual fodder deemed appropriate for both the working classes and the young. Cows were not to be found in stories and riddles, but were known only as a type of graminivorous ruminating quadruped with several stomachs. Their experience was not just verbal: it was also a practical one:

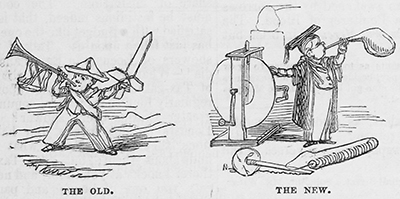

Fig. 1. Old and New Toys, Punch (1848). One of several illustrations accompanying a satirical article that compared the traditional toys of the nursery with suggested improvements for Victorian Britain. Alongside other depictions of a megatherium rocking-horse and a hot air balloon kite, it recommended replacing a trumpet and toy sword with a blowpipe and an electrical machine.

The little Gradgrinds had cabinets in various departments of science too. They had a little conchological cabinet, and a little metallurgical cabinet, and a little mineralogical cabinet; and the specimens were all arranged and labelled, and the bits of stone and ore looked as though they might have been broken from the parent substances by those tremendously hard instruments their own names

This presentation skewered a particular mode of teaching; however, whereas the five Gradgrind children had only grown up with their ological cabinets and fact-filled speeches, for many other children in Victorian Britain such hands-on scientific investigations were practised alongside and as part of other types of activities.

Far from being dusty fact-crammers, Victorian science books and articles, shows and activities, artefacts and pastimes, were explicit attempts to combine education with entertainment; or, in the favoured phrase of the day, instruction and amusement. Analysing these books, objects, and activities elucidates their content and intent and impact; they were evidently much more than Gradgrindian stereotypes. We will discover that fairy tales might have been made to look a lot like science; but also that scienceas Dickenss oriental simile in my opening example reminded uscould look a lot like fairy tales as well.

Many Victorian audiences would have been familiar with Dickenss characterization of attempts to instruct wider publics in scientific subjects. The second quarter of the nineteenth century had been rife with movements toas it was seencompensate for both expert and lay deficiencies in scientific understanding. The so-called gentlemen of science had combated a perceived decline in British capabilities with calls for the reform of university syllabi and the defining of new roles for scientific practitioners, and founded the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1831, whose peripatetic annual meetings would continue throughout the century as a touchstone for current debates, and as fodder for the periodical press.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain»

Look at similar books to Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Science in wonderland: the scientific fairy tales of Victorian Britain and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.