1. Early Ideas

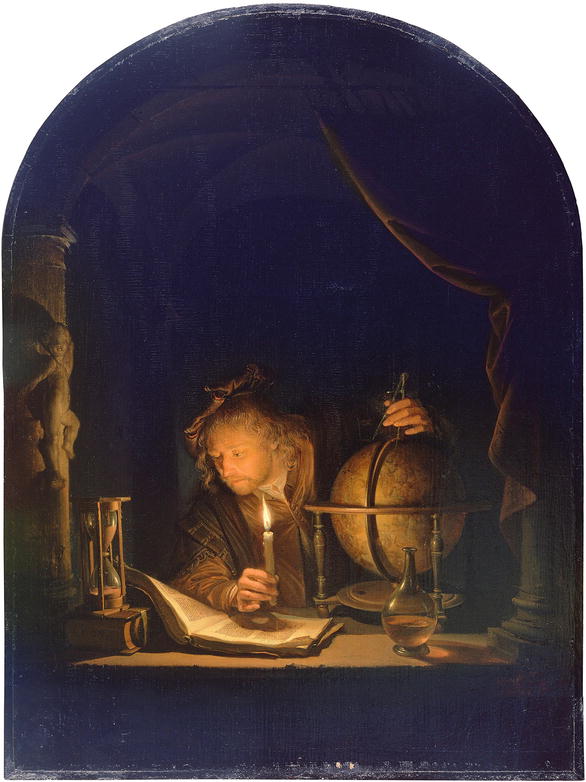

Fig. 1.1

The Flemish painter Garrit Dou (16131675) crafted this masterpiece of an astronomer working by candlelight. The scholars tools include a liquid-filled beaker, an hourglass, a huge book, and a celestial globe showing the constellations of the night sky. Although telescopes were invented at the opening of the seventeenth century, most early astronomers did not have access to them; the objects in the painting were the tools of their trade. At the end of the day, the ancient student of the sky could only dream of what travelers might discover out there (Painting by Garrit Dou, ca. 1658)

In the first century a.d. , Greek Hellenistic thought and culture continued a centuries-long spread throughout the western world. While the Mayan kingdom debuted its long count, Chinas Han dynasty officially adopted Confucianism, and a Jewish rabbi was stirring things up in the Middle East, Lucian of Samosata was quietly writing a story about travel to the Moon. As with much fiction, his was more a commentary and satire of contemporary literature than a narrative of imagined events. Lucian didnt have much hard science to go on in the first century.

Lucians True History detailed a nautical voyage of discovery interrupted by a violent waterspout. After a harrowing, windy week, the narrator and his intrepid crew found themselves deposited on the Moon. Lucian described his voyage:

[O]n the eighth day we saw a great country in it, resembling an island, bright and round and shining with a great light. Running in there and anchoring, we went ashore, and on investigating found that the land was inhabited and cultivated. By day nothing was in sight from the place, but as night came on we began to see many other islands hard by, some larger, some smaller, and they were like fire in color. We also saw another country below, with cities in it and rivers and seas and forests and mountains. This we inferred to be our own world.

Lucians story, written some nineteen centuries ago, includes elements of space travel, encounters with aliens, artificial atmosphere, and even the scientific desire to explore and discover. The Moon continued to be the central object of cosmic speculation for centuries to come.

In September of 1610, German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler wrote a short paper confirming Galileos discovery of Jupiters four large moons. It was called, simply, Observation-Report on Jupiters Four Wandering Satellites. The pamphlet marked the first time that anyone had referred to moons of other planets as satellites. Kepler may have had in mind Jupiters royal standing as king of the planets. In Keplers day, heads of state and other important figures surrounded themselves with a cadre of fans doubling as bodyguards. These early paparazzi were known by the Latin word satellitem . (Kepler had used the term in a letter to Galileo as well.)

Kepler didnt limit his writing to scientific journals. Over a period of 20 years, he transformed his 1608 student dissertation into what many consider to be the first work of modern science fiction. Called Somnium , the story was actually published after Keplers death in 1630. Keplers narrative opened as he was reading a book by a magician. He fell asleep (the magicians writing must not have been very engaging) and dreamed of an Icelandic boy taken to the Moon by daemons, kindly spirit-guides. Inhabitants of the Moon called it Levania.

Keplers story anticipated many scientific issues, such as atmosphere (his travelers must have moist sponges over their nostrils to breathe), the cold of space (travelers wrap themselves in blankets), and great distances between Earth and the Moon. Like any good science fiction, Keplers writing echoed scientific thinking of the time. It described the appearance of eclipses from the Moon; it portrayed the size of planets as changed because of the Moons distance from Earth; it even gave a guess as to the size of the Moon and described the effects of lunar tidal lock (the phenomenon of the same side of the Moon always facing Earth). Sadly, Kepler awakened before we could learn about such subtleties as good landing sites and lunar mascons.

It would be many decades before writers tackled the nature of the outer Solar System, let alone the idea of exploring those distant worlds. Dutch mathematician Christian Huygens was undaunted by distances and rudimentary instruments. Huygens studied the cosmos at the end of his 50-power telescope, where he made such discoveries as Saturns moon Titan, the length of a Martian day, and details of the Orion and other nebulae. In his 1698 book The Celestial Worlds Discoverd: Or, Conjectures Concerning the Inhabitants, Plans and Productions of the Worlds in the Planets , Huygens examined the nature of outer planets, especially as they related to clouds and water:

[A]bout Jupiter are observd some spots of a darker hue than the rest of his Body, which by their continual change show themselves to be Clouds Since tis certain that Earth and Jupiter have their Water and Clouds, there is no reason why the other Planets should be without them. this Water of ours, in Jupiter or Saturn, would be frozen up instantly by reason of the vast distance of the Sun. Every Planet therefore must have its Waters of such a temper, as to be proportiond to its heat.

Significantly, Huygens went on to speculate about the moons of the outer planets.

[ A]ll the Attendants of Jupiter and Saturn are of the same nature with our Moon, as going round them, and being carryd with them round the Sun just as the Moon is with the Earth. Their Likeness reaches to other things, too whatsoever we can with reason affirm or fancy of our Moon (and we may say little of it) must be supposd with very little alteration to belong to the Guards of Jupiter and Saturn, as having no reason to be at all inferior to that.

The idea that the moons of Jupiter and Saturn are similar to our own Moon carried well into the decade of the 1960s. In intervening years, literary characters visited our own Moon, and witnessed the first human expedition to Neptune in Hugh Walters 1968 novel Nearly Neptune .

Fig. 1.2

Drawing of Saturn and its rings by Christiaan Huygens, ca. 1659. Note his comparison to Earth at right (Image from Systema Saturnium )

Mars continued to be the driver of interplanetary travel tales, with Percival Lowell unwittingly at the helm. In his wildly popular and supposedly non-fiction book Mars as the Abode of Life , Lowell declared:

Thus, not only do the observations we have scanned lead us to the conclusion that Mars at this moment is inhabited, but they land us at the further one that these denizens are of an order whose acquaintance was worth the making.

The novelist Edgar Rice Burroughs, famous for his Tarzan tales, fully embraced Lowells thoughts on Mars, spinning a series of narratives populated by six-legged tiger-like Thoats, green four-armed Martian insect men, and of course, a beautiful princess, Dejah Thoris.

Burroughs paints a picture of Dejah Thoris and her Martian civilization as attempting to preserve Mars dying atmosphere, something Lowells observations certainly inspired. Here, she berates the brutish green Martian race for their lack of understanding: