ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My primary thanks go to Dru Butterfield, natural resources manager, and Brian Carter, natural resources specialist, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District. Both were unfailingly generous with time, energy, loan of office space, and good-natured answering of pesky questions.

All photographs in this book are courtesy of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District, unless otherwise noted. My deep appreciation goes to everyone who has helped over the years to preserve the locks remarkable archives.

Thanks also to the following: my editor at Arcadia, Julie Albright, queen of the cheerful e-mails; my wife, Karen Kent, who said she believed me when I explained that hanging around at the locks, watching boats, was just research; our daughter, Leah Woog, who lent me her photographs for a bargain price; Jay Wells, visitor center program director, and Susan Connole and Brad Carlquist, visitor center staff, for sharing so freely and enthusiastically; Stu Witmer and Phil Roush, for arranging a memorable jaunt on the water; and HistoryLink.org , an invaluable resource for any Washingtonian curious about the states past. A grateful tip of the hat goes to it and the spirit of its creator, the latebut clearly immortalWalt Crowley.

Also helpful were Carolyn Marr, librarian of the Museum of History and Industry, Seattle; Mary Ann Gwinn, book editor of the Seattle Times ; Louise Richards of the Fisheries-Oceanography Library, University of Washington; Richenda Fairhurst; Robert Fisher, collections manager of the Wing Luke Asian Museum; Tom Dean of the Boeing Employees Concert Band; and Leslie V. Unruh and the Coal Creek Jazz Band.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chrzastowski, Michael. Historical Changes to Lake Washington and Route of the Lake Washington Ship Canal, King County, Washington . Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, USGS, 1981.

Dorpat, Paul, and Genevieve McCoy. Building Washington: A History of Washington State Public Works . Seattle, WA: Tartu Publications, 1998.

Ficken, Robert E. Seattles Ditch: The Corps of Engineers and the Lake Washington Ship Canal. Pacific Northwest Quarterly , January 1986.

Freier, Renee L. Historic Grounds ReportThe Carl S. English Botanical Garden . U.S. Army Corps of Engineers document, 1989.

Gearin, Patrick J., et. al. Results of the 19861987 California Sea LionSteelhead Trout Predation Control Program at the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks . NOAA and Washington Department of Wildlife document, 1988.

Larson, Suzanne B. Dig the Ditch! Boulder, CO: Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education, 1975.

Seattle District Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Lake Washington Ship Canal Historic Properties Management Plan . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1998.

Warren, James R. King County and Its Queen City, Seattle: An Illustrated History . Woodland Hills, CA: Windsor Publications, 1981.

Willingham, William F. Northwest Passages: A History of the Seattle District U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 18961920 . Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 2006.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old

stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

THE EARLY DAYS

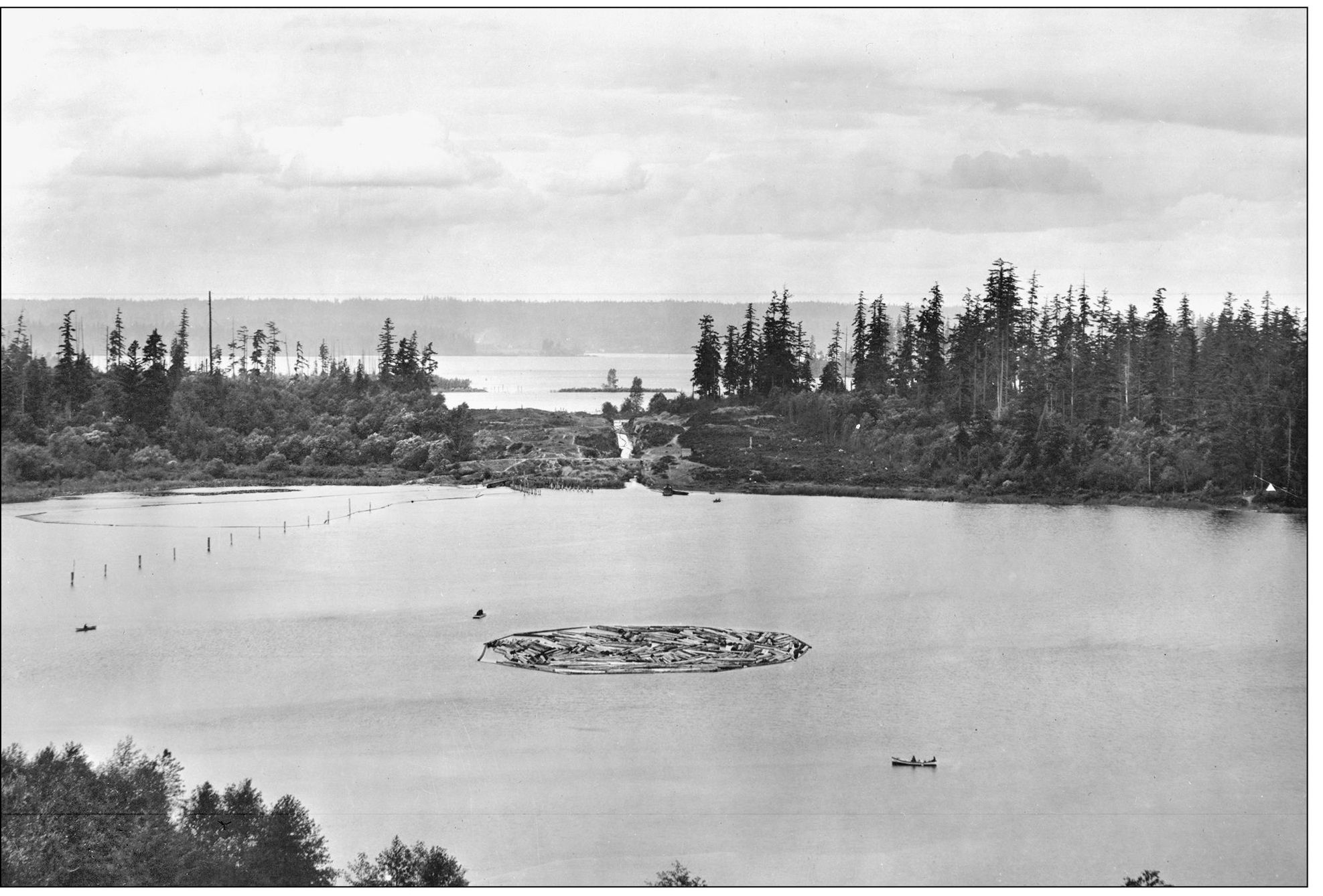

When the first white settlers arrived in Seattle in the 1850s, the area was rich in natural resources, particularly timber and coal. However, transporting these resources was cumbersome and slow. Just getting coal from the Cascade foothills to the Seattle depot at Elliott Bay, for instance, required 11 transfers from water to land and back again.

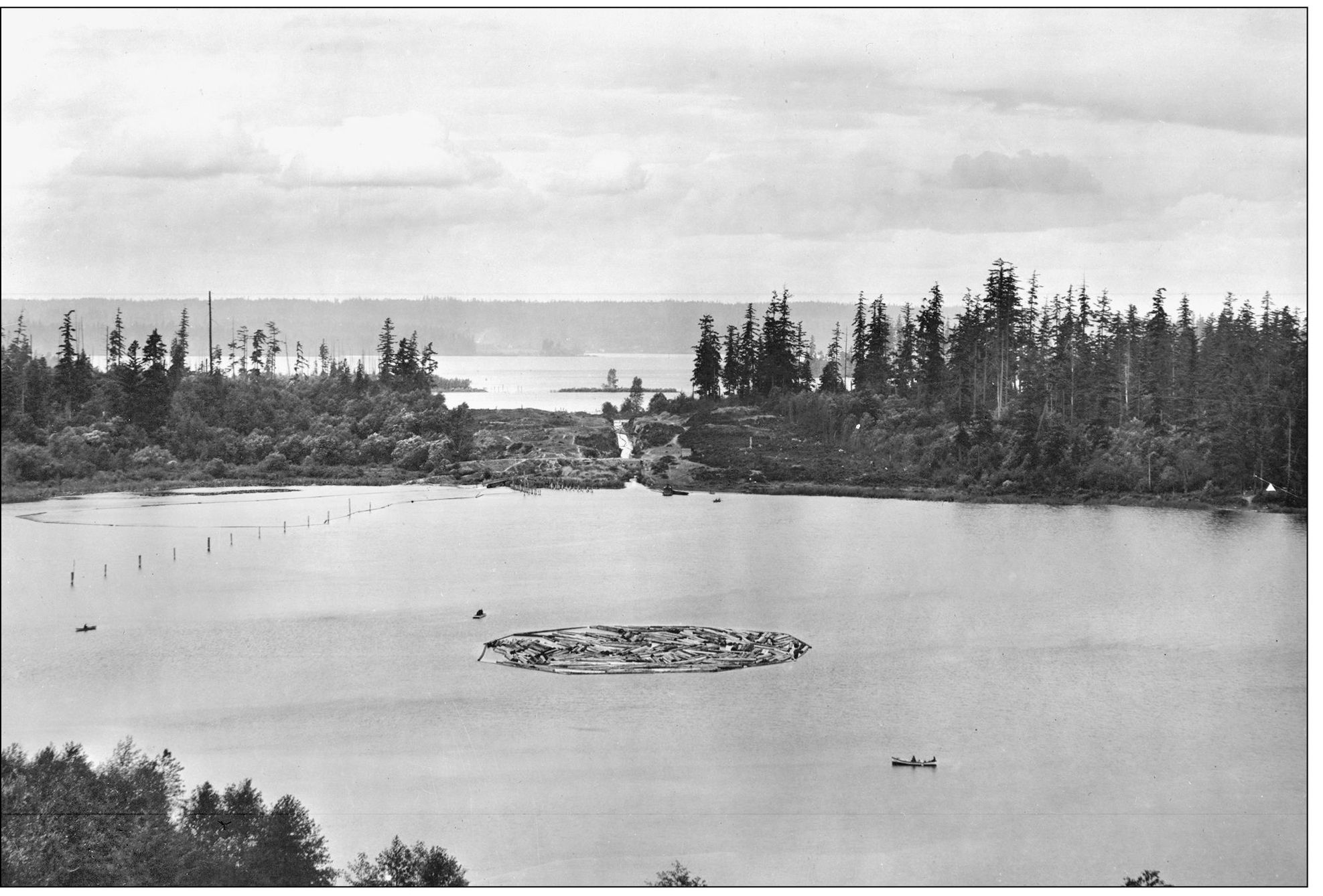

One answer to the problem was to use Seattles bountiful bodies of waterits saltwater bays, freshwater lakes, rivers, and streamsfor transportation. Connecting these bodies of water via man-made channels would vastly improve the movement of materials and resources. There were several other advantages to connecting saltwater with fresh. Freshwater wharves would make possible the loading of cargo at any time, not just at high tide. Ships moored in freshwater wharves would be less prone to rot. And lakefront shoreline, if easily accessible from the sea, would be available for industrial development. Connecting the regions natural bodies of water was proposed very soon after Seattle became a permanent settlement. One of the towns best-known pioneers, Thomas Mercer, publicly suggested it in 1854. During the new communitys first Independence Day celebration, held on the shores of the lake called tenas Chuck in the Chinook trading jargon, Mercer proposed that a canal be dug connecting the regions two main lakes with Puget Sound. Mercer then renamed tenas Chuck Lake Union, suggestive of a future union of these waters.

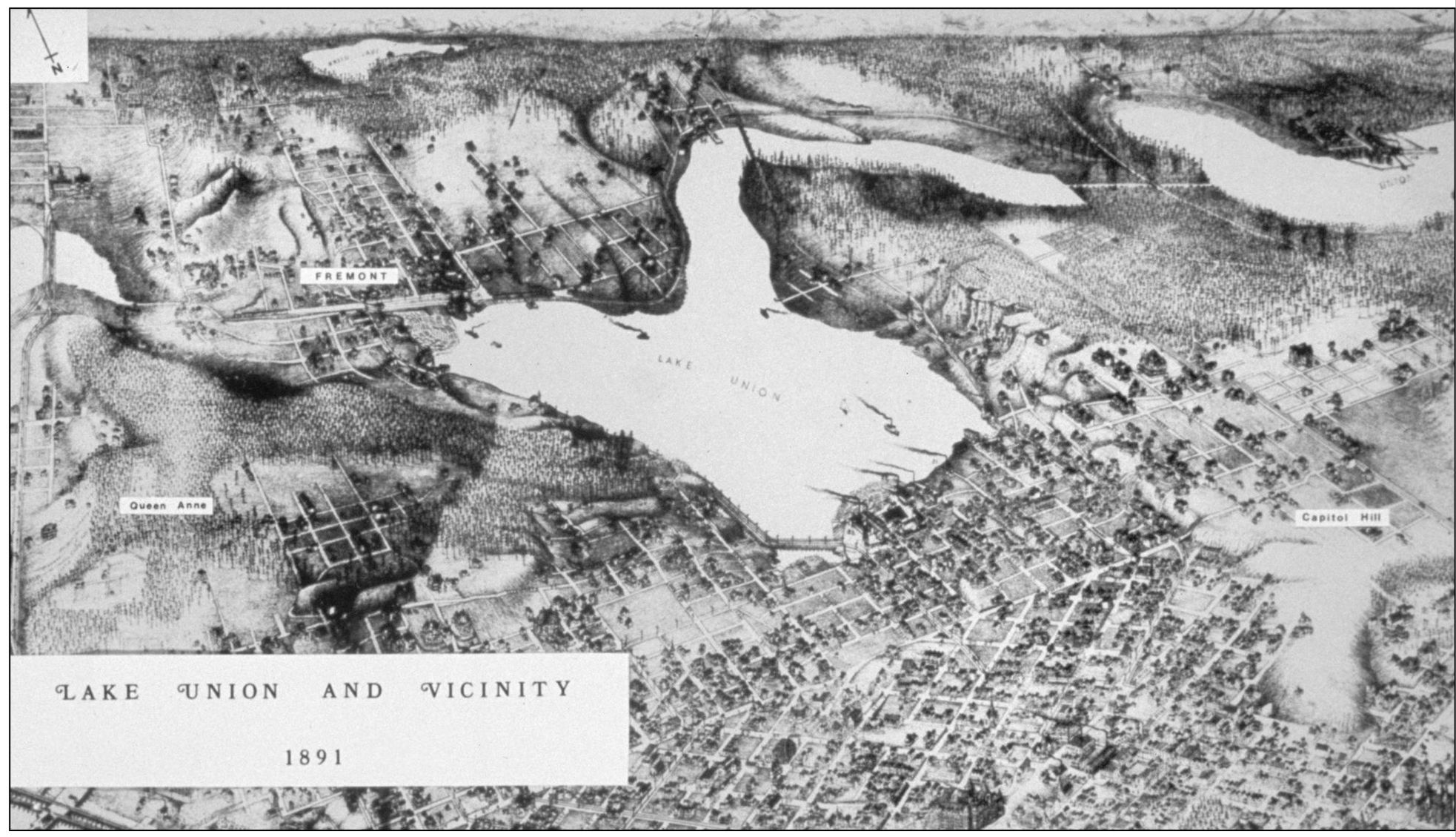

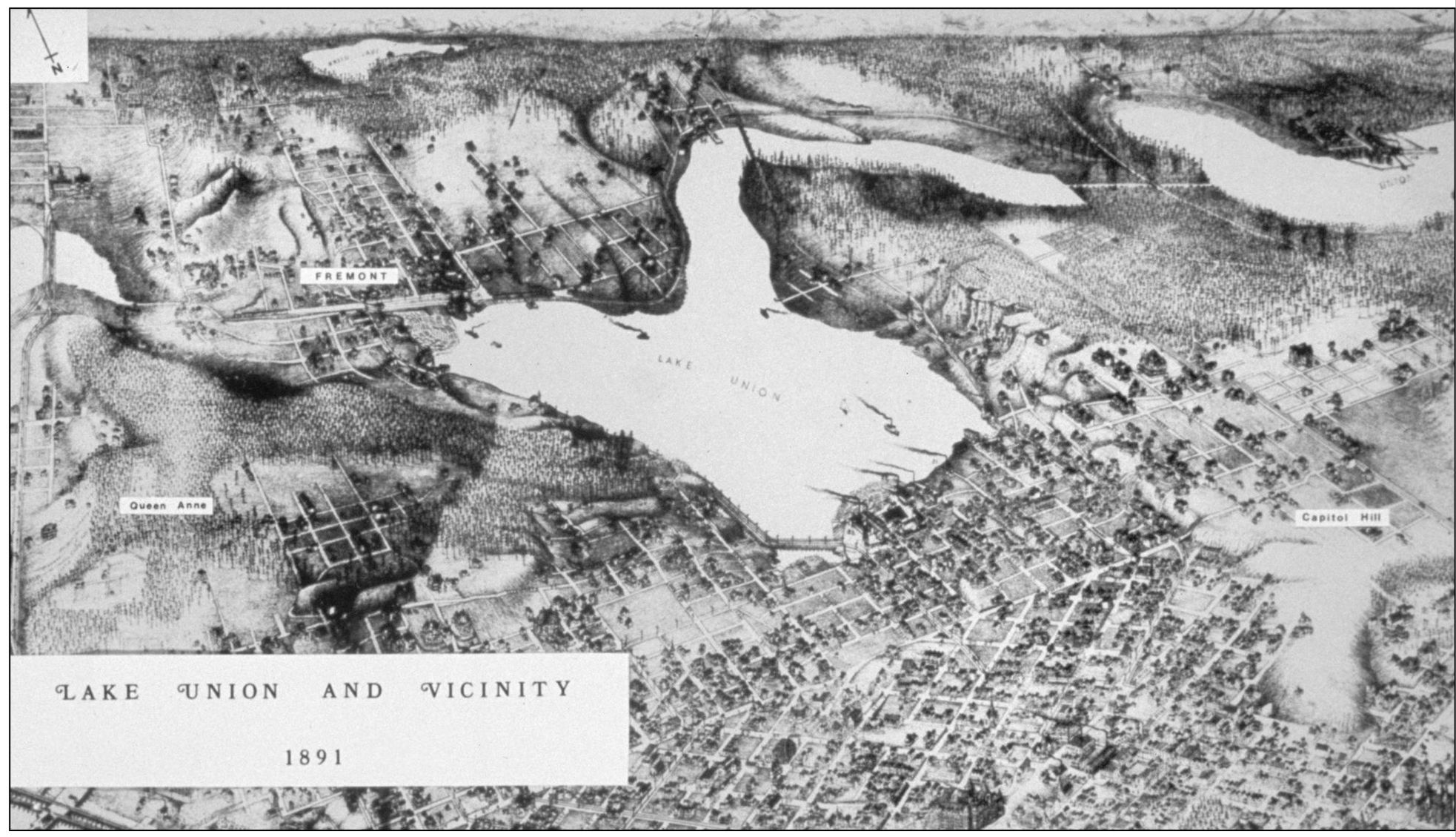

Despite setbacks, including the Great Seattle Fire of 1889 and a national depression, the region grew quickly. During the 1890s, Seattle nearly doubled in population to more than 80,000. The discovery of gold in the Yukon spurred growth, since Seattle was a major stocking-up and jumping-off point for hopeful prospectors. Also, the completion of a train line made Seattle far more accessible. Part of this growth was industrial development. For example, the mills of Ballard thrived, turning out 40 million feet of lumber annually in the early part of the decade. Ballard became the worlds leading manufacturer of shingles. This 1891 map shows Seattle as it grew around Lake Union. The Lake Washington Ship Canal would eventually connect Lake Union (in the center of the map) with the much larger Lake Washington (to the east) and Puget Sound (to the west). However, situating the canal on this route was not a given. Seattleites have always been outspoken and contentious regarding transportation systems, and this was no exception. As the region grew, a number of possibilities were explored.

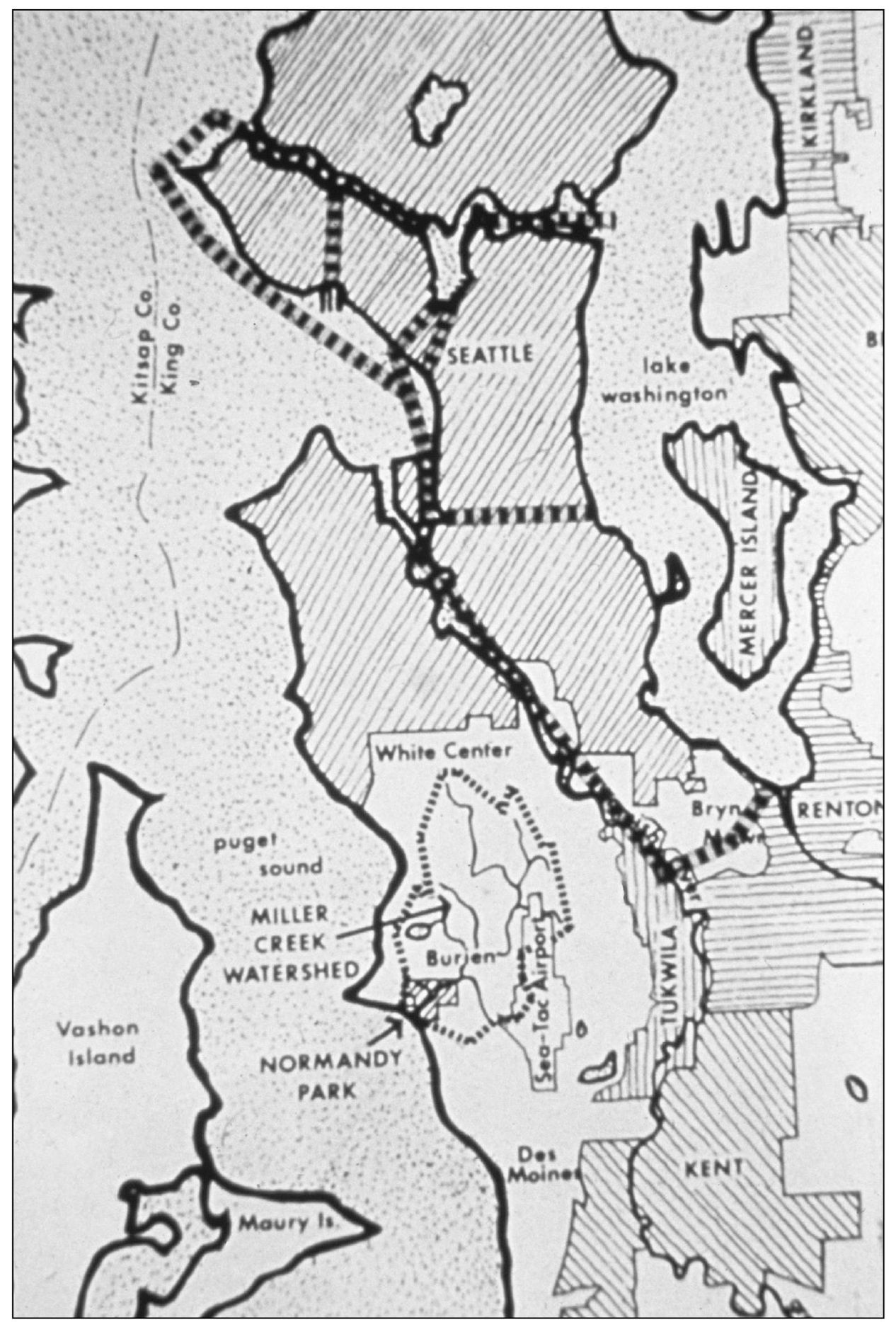

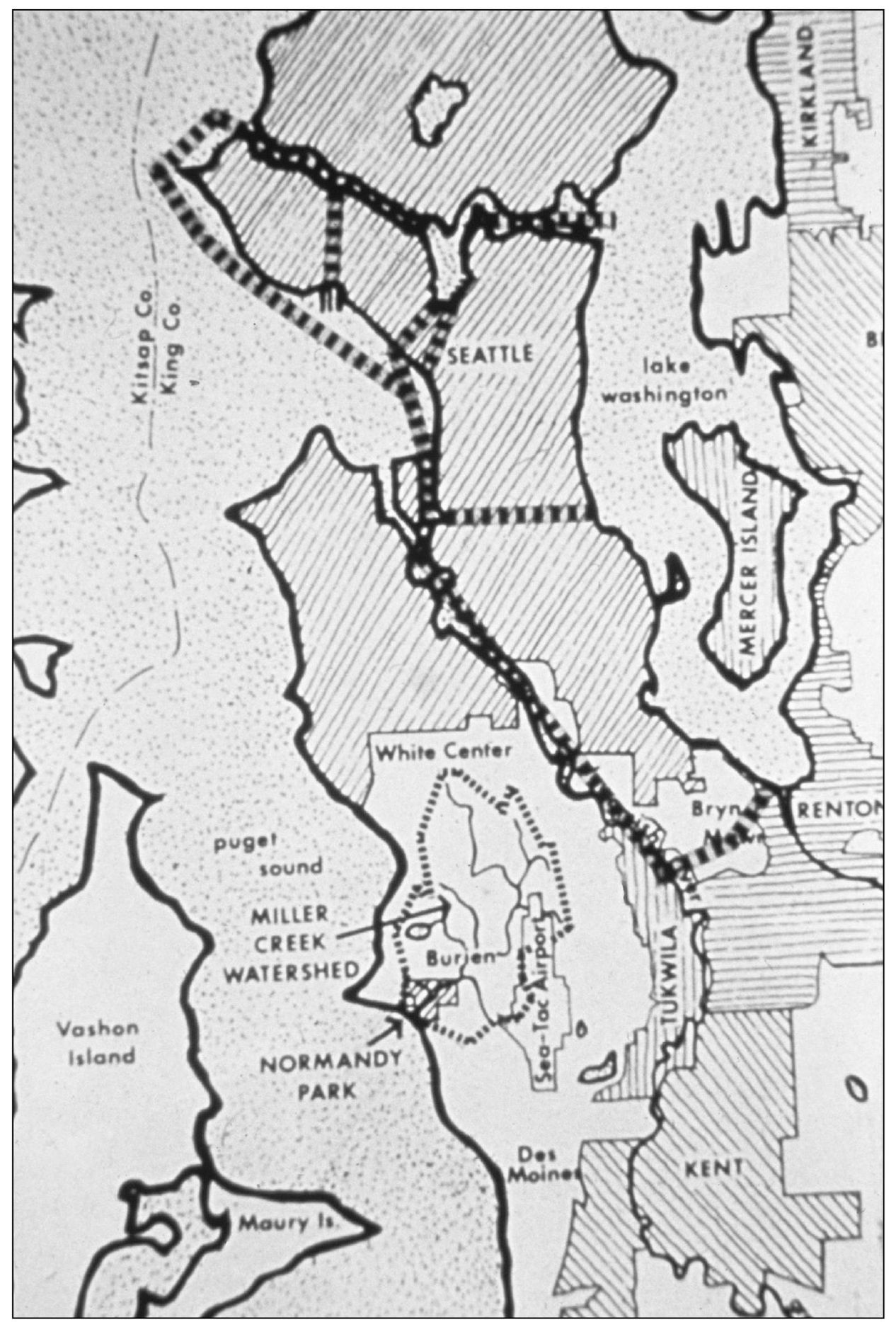

One possibility followed Lake Washingtons natural outlet, south of what is now downtown Seattle. However, a canal along this route would have required constant dredging. Also considered was a route from Lake Washington to Smith Cove (the site of the present-day Elliott Bay Marina) in Elliott Bay. The Corps of Engineers favored this route, in part because it promised the greatest security from naval attacks. However, for some time, it did not actively pursue the matter, mostly because of a lack of support from government authorities outside the region. Furthermore, the influential owner of the Great Northern Railway, James J. Hill, objected to this particular route (it interfered with his plans). He favored the route that was eventually adopted. This map shows several contenders for the canal route. At top is the Lake WashingtonLake UnionSalmon Bay route (the one eventually chosen). The lines from the south end of Lake Union to Elliott Bay mark the so-called Smith Cove route. Below that, bisecting Beacon Hill, is the route of Semples Canal. And the southernmost route follows the natural outlet of Lake Washington.