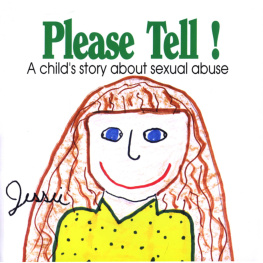

In March I saw the first skylark. Not the bird, of course. On our high, windswept moors, it was much too early in the year for skylarks. This one had been drawn on a sheet of A4 paper, the ordinary kind you put in printers, and at first glance I missed the bird altogether. Meleri reached across to point to the very bottom right-hand corner. Putting on my reading glasses, I held the paper up to the car window to see a drawing that was not much bigger than my thumbnail. The weather was being typically Welsh that day, heavily overcast and mizzling too heavy to be mist, too light to be drizzle making the back seat of the car as dim as a disused chapel. On the page, the tiny bird crouched midst blades of prickly looking grass, its eyes bright, its expression shrewd, as if it knew something I didnt. Its plumage was highly coloured, more that of a macaw than a skylark. Minuscule musical notes rose up along the right-hand edge of the paper to indicate its song.

Dont you think that shows talent? Meleri asked. Shes only nine.

Whats her name again?

Jessie. Jessie Williams.

The tiny details of the drawing, so precise and intricate, mesmerized me.

Meleri opened the elasticated portfolio file resting on her knee and took out three more drawings and handed them to me. Two were done in felt-tip pen like the one I already held. The other was in pencil, the lines so pale and spidery that I could hardly make them out in the dim light. The same small bird locked eyes with me in each of them.

I like that she does them, Meleri said. They seem cheerful to me. As if Jessie still has hope.

I had met Meleri Thomas the first time a number of years earlier. It was in Cardiff, in the green room of a TV studio for the Welsh-speaking channel S4C, where we were both appearing on the morning breakfast show. I was there to promote one of my books, and she was taking part in a panel discussion about childrens rights. Meleri caught my attention immediately, because chances are she would have caught anyones attention. Her features were bold, attractive, almost Italianate large dark eyes and long, dark hair and she was dressed in a figure-hugging knit dress in a startling shade of emerald green. These aspects would have been striking enough on their own, had there not also been the fact that Meleri looked remarkably similar to popular TV chef Nigella Lawson. For just a moment I thought thats who it was and was curious why she would appear on a Welsh-speaking panel about childrens rights.

Green rooms always have an edgy atmosphere. Almost everyone waiting to go before the television cameras feels anxious for one reason or another, and as a consequence, even if you dont know each other, its common for people sitting together in a green room to make small talk as a distraction from nerves. This was challenging for me on this particular occasion, because everyone was speaking Welsh. I had only newly learned the language and was not quite fluent. More to the point, my American tongue still did not always take kindly to Welsh pronunciations. Subsequently, my only real memory of that occasion was the clanger I dropped. The weather always being a good topic for small talk, Id thought to remark on how much I was enjoying the crisp frosty days we were having. In the unanticipated hilarity that followed, I discovered the Welsh word for frost is pronounced remarkably similarly to the Welsh word for sex.

When Meleri and I met again, it was at a small conference for social workers and other youth support workers, once again in Cardiff. I recognized her flowing black hair and glamorous clothes immediately. We laughed at the memory of my embarrassing blooper, and I was forced to admit that my Welsh was even worse these days than it had been then, as Id moved to a new area where the dialect was much different. While I still read the language reasonably well, Id pretty much stopped speaking it.

Thats my area, Meleri said, as I was explaining this. Thats where I live! And then, Oh, if youre so close, please, you must come out to Glan Morfa. I have so many children Id love you to see.

It took two more years before I found myself being driven along a largely urbanized beachfront that segued from one coastal town to the next on the way to the childrens group home, Glan Morfa.

The whole area was run down, from the derelict industrial port built to serve now-disused quarries to the dreary pleasure beach with its broken roller coaster and shuttered kiosks. Then came the endless miles of holiday parks, row after row of faded caravans tinged with rust, all empty in the off season.

The car turned down a long single lane between two of these caravan parks. The road was badly potholed, so we slowed to a crawl. Indeed, it was such a bumpy ride we couldnt help but laugh in the back seat because we were so jostled, but then through a small grove of scraggy trees deformed by the sea wind, a long, low building appeared. Its stripped back, brutalist architecture hinted at a 1960s construction date. The white paint around the windows was peeling. The pebbledash walls were the colour of porridge. Meleri sensed my dismay at such bleak surroundings and said, Were hoping the council can afford to paint this year, although I think they are going to spend the money on repairing the road.

Inside, however, was a different world. The entrance area was well lit and painted in white and bright gradations of turquoise. There were posters up and photographs on a bulletin board of group activities and days out. At the far end was a glassed-in office with a calendar, individual schedules and numerous photos of the children on the walls. I was introduced to Joseph and Enir, the staff in charge.

As I entered the office area, Enir flipped on the electric kettle, took out four mugs and measured instant coffee into them. You take it white? she asked, and added milk before I answered. Joseph opened a round purple tin to reveal an assortment of biscuits. Youre in luck, he said cheerfully. There are still some Penguin bars left. He handed one to me.

We spent a very pleasant fifteen minutes getting acquainted. Enir was twenty-eight. Shed been working at the group home for four years, liked the shift work because it fitted in well with her young daughters schedule at school and was looking forward to her holiday in Majorca in the summer. Joseph looked to be in his early forties. He had been working at Glan Morfa for almost ten years, longer than anyone else, and was now the day manager. He liked the work, he said. He realized for most people it was not a career, but for him it was. He enjoyed being on the front line, as he put it, where he could help the children coming to Glan Morfa grow and change while they were there. He tried to give them a sense of belonging, a sense of being cared for, and this seemed to have happened, as several of the graduates the children who had reached eighteen and moved out of the Social Services system still returned regularly to visit Joseph.

After wed shared coffee, Meleri and Joseph took me down a hallway adjacent to the office and into a small room crammed with furniture. Two brown armchairs and two small filing cabinets were against one wall, and a well-worn beige sofa was against the opposite one. In the middle, with just barely enough room to get around it, was a sturdy wooden table with a white-patterned Formica top and four orange plastic chairs pushed up to it.

It isnt grand, Joseph said. His tone wasnt apologetic, just matter of fact. But this is our therapy room. Or should I say therapy room in quotes, because its also the conference room, the interview room, the I-need-to-get-this-kid-out-of-the-chaos-and-talk-to-him room and, as you can see, the store room.

Meleri had gone to get Jessie, so I chose a chair on the right-hand side of the table and sat down.