Elite 110

Sassanian Elite Cavalry AD 224642

Dr Kaveh Farrokh Illustrated by Angus McBride

Consultant editor Martin Windrow

CONTENTS

SASSANIAN ELITE CAVALRY AD 224642

ORIGINS OF THE SAVARAN

W hen the Sassanians overthrew the Parthians at Firuzabad in AD 224, they endeavored to recreate the Achaemenid superstate that encompassed Iranian-speaking peoples from Central Asia to the Kurds, Medes, and Persians of the Near East. Despite their overthrow by Alexander the Great in 333 BC, the Achaemenids had laid the technological and tactical foundations of the future Sassanian elite cavalry, the Savaran knights.

The failed invasions of Greece under Darius I and his son Xerxes resulted in major changes in the equipment of infantry and cavalry. By the time of Alexanders conquests, Persian cavalry were described by Herodotus as being equipped with bronze cuirasses, scale armor and helmets, thigh pieces, maces, javelins, daggers, the kopis slashing sword, quivers holding 30 arrows, bows, and, by the end of the empire, javelins and lances. Horses also had bronze armor comprising frontlet, breast armor and thigh protection. This technology first developed among Iranian peoples in Central Asia, specifically Chorasmia (modern Uzbekistan). It was here that the concept of heavy cavalry was developed and brought to the Near East by the Achaemenids of Persia. The agriculturally settled Chorasmo-Massagetae peoples had developed a weapon to counter steppe cavalry. Heavy cavalry (with armor for man and horse) was an early tactical answer to the fast and agile mounted bowmen of the steppes. Chorasmian heavy armored cavalry may have used the tactics of close order attack (see Michalak, 1987, p.74). This early heavy cavalry was the Iranian counterpart to the classical Hellenic infantry phalanx. These cavalrymen wore scale armor, and carried what appears to be a long lance. Their horses also had armored protection.

A gigantic eagle gently lifts a woman with its claws, on a late 6th- to early 7th-century metalwork plate. The eagle motif was one of the standard symbols of the Savaran. (State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg)

How much influence did the Massagetae have on their Iranian kinsmen in Achaemenid Persia? Later Achaemenid heavy cavalry certainly adopted the armor technology of the Massagetae and classical sources do refer to Massagetan cavalry among the Achaemenids. Nevertheless, a local Persian force rapidly appeared. These were recruited from the ranks of the Azata or upper nobility who were of Aryan descent. Xenophons Kyropaidia notes that the early Persians had few cavalry however by the time of the Greek wars, Persia fielded large numbers of effective Chorasmian-inspired cavalry. The two-handed lance is first seen in lightly armed northern Iranian Chorasmian horsemen. Its adoption by the heavy cavalry of the Achaemenids was the first true representation of the prototype knight. Persian Azat knights often settled their disputes with cavalry and it was here that the Zoroastrian concept of Farr (divine glory) and north Iranian warfare evolved into the man-to-man joust. Rebels and members of the royal house often settled disputes by way of the joust as corroborated by Greek sources. The relatively brief Hellenic interlude of Alexander the Great and the Seleucids did not eradicate this Iranian culture.

However, heavy cavalry in Achaemenid Persian armies never developed into the main striking force that they were to become in the later Parthian and Sassanian armies. A very important implication of the Persian-Hellenic wars was that lightly armored troops could not withstand the excellent training and leadership of the standard Greek hoplite or Macedonian phalanx formation. Heavy cavalry units did achieve fleeting local successes, but could not compensate for the weaknesses of the Achaemenids against Hellenic armies. More importantly, Alexander had perfected the tactic of a truly integrated combined arms force, in which infantry and cavalry operated closely together. Nevertheless, the meteoric scale of Alexanders victories largely overshadowed the future dangers of a revived Persia in the form of professional armored cavalry, a warning voiced earlier by Xenophon.

The post-Alexandrian Seleucids also inherited Achaemenid-style heavy cavalry units. Units of these were operating with Antiochus III in his wars with the Romans. The Parthian cataphractii in turn defeated the Seleucids in western Iran and Mesopotamia in the 2nd century BC. Parthian cavalry had developed much of its tactics to successfully counter Macedonian heavy infantry and tactics. They were similar to the north Iranian Saka and earlier Massagetae. The Parthians did much to bring the styles of their north Iranian kin to Persia. Their battle tactics were simple and effective. Lightly armed horsemen came equipped with their chief weapon: the bow. They were adept horse archers who supported the armored knights who employed spear and sword on their famous Nisean chargers. The Parthian cavalryman typically wore a strong cuirass and a helmet with faceguard, and his horse was protected by an armored coat.

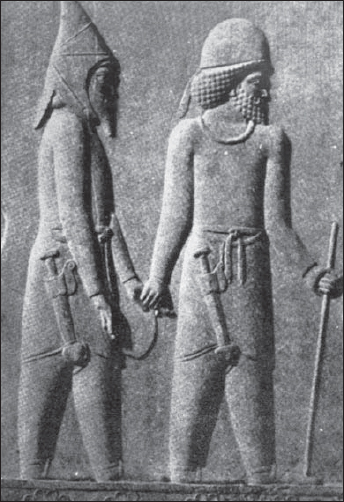

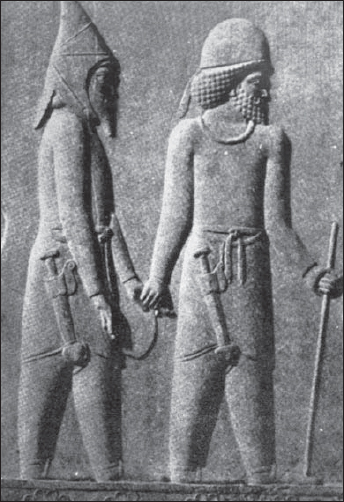

Persian (right) and Mede (left) Achaemenean noblemen at Persepolis. The Sassanians endeavored to recreate a pan-Iranic empire with the Savaran as its elite military arm. (Khademi, Modaress University)

By the early 3rd century AD the Iranian peoples of the empire no longer trusted Parthian abilities in safeguarding Persia against Roman incursions. When Ardashir and his son Shapur overthrew the Parthians in AD 224, Iranian highlanders (Medes, Kurds, northern Iranians), Persians, and eastern Iranians joined the Sassanian banner. Many Parthian families such as the Mihran and Suren followed suit. The Sassanians inherited the Parthian military tradition of having cavalry as the mainstay of the armed forces. However, they were to introduce major tactical and technological changes to the heavy armored knight throughout their reign.

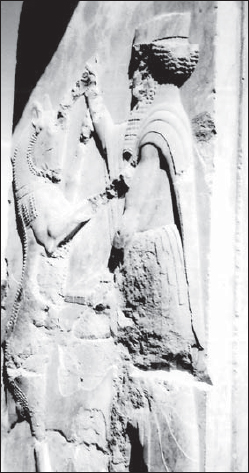

Darius the Great battles an incarnation of evil. The Sassanians revived much of the symbolism and regalia of the Achaemenid dynasty, which had been destroyed in the 4th century BC by Alexander the Great. (Authors photo at Persepolis)

A strategic problem faced by the Parthians and then the Sassanians was the constant threat of a two-front war: one in the east, the other in the west. On the western front stood first the formidable Romans and then the Byzantines. The east was menaced by Hun and Turkic warriors. The logical strategy was the development of a highly mobile and professionally trained cavalry force able to deploy at short notice at any potential front. The Parthians had wisely chosen not to rely on infantry formations against the Roman legionaries as they were possibly the worlds best trained heavy close-combat infantry. In any event, infantry was practically useless on the open steppe spaces of northeastern Persia and Central Asia against the deadly and agile nomadic cavalry.

The Sassanians were the other superpower, east of the Romans. In almost every battle with Rome, the Savaran cavalry were present. Their military machine proved to be Romes equal, an unpalatable truth which the Romans were eventually forced to accept (see Howard-Johnson, 1989). Scholars, popular imagination, and the media are excited by the likes of Alexander, Caesar, Hannibal, Attila, and Napoleon, but few know of Shapur I (24172), who defeated three Roman emperors in his lifetime, or the death of Julian the Apostate in Persia, an event which ensured Christianitys survival in the West. Sassanian elite cavalry were key in preventing Rome from absorbing Persia and reaching the borders of India and China. Very few today realize the awe and fear that the Savaran inspired in their opponents. Libianus comments on the Romans who prefer to suffer any fate rather than look a Persian in the face (Libianus, XVIII, pp.20511). The Sassanian Savaran in turn left their imprint on the Romans (and through them, the Europeans in general), as well as the Arabs and the Turks. The Savaran did much to avenge Alexanders conquests centuries before, leaving behind an impressive legacy, which today is all but forgotten.

Next page