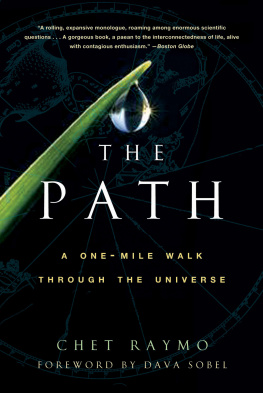

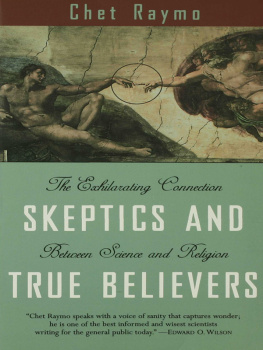

WALKING

ZERO

DISCOVERING COSMIC SPACE

AND TIME ALONG THE

PRIME MERIDIAN

Chet Raymo

Copyright 2006 by Chet Raymo

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

First published in the United States of America in 2006 by

Walker Publishing Company Inc.

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from

this book, write to Permissions, Walker & Company,

104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products

made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The

manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations

of the country of origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

eISBN: 978-0-802-71827-3

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 3 3 1

There are no privileged locations. If you stay put, your place maybecome a holy center, not because it gives you special access to thedivine, but because in your stillness you hear what might be heardanywhere. All there is to see can be seen from anywhere in theuniverse, if you know how to look.

Scott Russell Sanders

CONTENTS

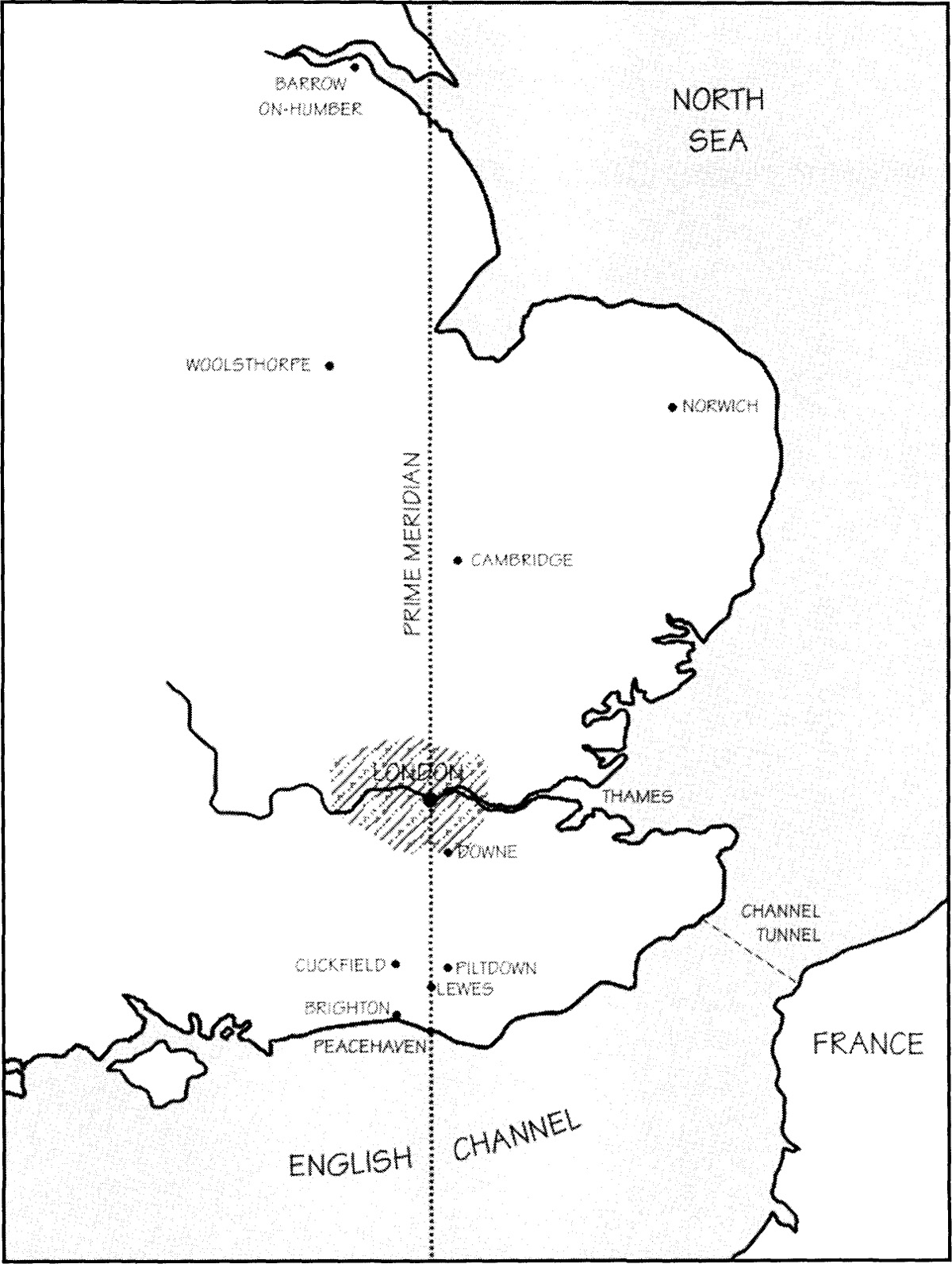

In the fall of 2003 I set out to walk along the prime meridianthe line of zero longitudeacross southeastern England. My choice of the Greenwich meridian was not arbitrary; through various accidents of history, the meridian is the touchstone by which the entire world measures place and time. The Royal Observatory at Greenwich, founded by King Charles II in 1675, has defined a common standard for maps and clocks since 1884. The meridian also passes close to a surprising number of other locations important in the history of science. Isaac Newton's chambers at Trinity College, Cambridge, are not far from the line, nor is his place of birth in Lincolnshire. Charles Darwin's house at Downe, in Kent, is two and a half miles from the meridian. And more, much more.

It would be hard to think of a walk of equivalent length anywhere in the world that would provide so rich a thread on which to hang a story of human curiosity.

Walking Zero is about the epic struggle to understand cosmic space and time. It is a story of constantly expanding horizons, of intellectual courage and physical adventure, of men and women who dared to believe that the universe was not centered on themselves. It is a story of the breaking of the cosmic egg, of a planet becoming conscious of itself, and of the discovery of an abyss of space and time that might in fact be infinite.

Science is often imagined as a soulless activity administered by men and women in white coats bent on removing spirit and meaning from the world. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Many courageous individuals have bucked reigning orthodoxies to let their imaginations soar where no one had gone before. Pioneers such as Nicolaus Copernicus and Charles Darwin were reluctant revolutionaries who understood that their ideas would be resisted by those who preferred familiar truths. Giordano Bruno, burned at the stake in 1600, paid the ultimate price for (among other things) surmising the multitude of worlds that we now take for granted. Galileo Galilei, as a blind old man, was forced to kneel before assembled churchmen and deny what he knew to be true, the mobility of the Earth.

Our ancestors, perhaps naturally, believed themselves to live at the center of space, coevally with time. "All the world's a stage," wrote Shakespeare, and he meant it quite literally: a stage for the drama of human affairs. Creation myths from around the world assume that the cosmos was created for us, that it is centered on us, and that time has no meaning other than as a frame for human history. Our discovery of cosmic space and timea universe of galaxies and geologic eons that makes no reference to human historymust be counted a triumph of human pluck and cunning. After all, who among us would not like to live at the center of the world? Surely, nothing can be more flattering to our sense of importance than to imagine that we are the measure of all things. To forgo the cozy human-centered cosmic egg of our ancestors requires courage and a willingness to contrive our own meaning in a universe that is vast beyond our imagining. In making the journey into cosmic space and time we surrender certainty for curiosity, simplicity for complexity, comfort for adventure. We are perhaps a bit frightened by the light-years and the eons, but we are proud of all that the human mind has come to know and privileged to share, even as spectators, in that epic quest.

Each of us is born at the center of the world.

For nine months our physical selves are assembled molecule by molecule, cell by cell, in the dark covert of our mother's womb. A single fertilized egg cell splits into two. Then four. Eight. Sixteen. Thirty-two. Ultimately, 50 trillion cells or so. At first, our future self is a mere blob of protoplasm. But slowly, ever so slowly, the blob begins to differentiate under the direction of genes. A symmetry axis develops. A head, a tail, a spine. At this point, the embryo might be that of a human, or a chicken, or a marmoset. Limbs form. Digits, with tiny translucent nails. Eyes, with papery lids. Ears pressed like flowers against the head. Clearly now a human. A nose, nostrils. Downy hair. Genitals.

As the physical self develops, so too a mental self takes shape, not yet conscious, not yet self-aware, knitted together as webs of neurons in the brain, encapsulating in some respects the evolutionary experience of our species. Instincts impressed by the genes. The instinct to suck, for example. Already, in the womb, the fetus presses its tiny fist against its mouth in anticipation of the moment when the mouth will be offered the mother's breast. The child will not have to be taught to suck. Other inborn behaviors will express themselves later. Laughing. Crying. Striking out in anger. Loving.

What, if anything, goes on in the mind of the developing fetus we may never know. But this much seems certain: To the extent that the emerging self has any awareness of its surroundings, itsworld is coterminous with itself. We are not born with knowledge of the antipodes, the plains of Mars, or the far-flung realm of the galaxies. We are not born with knowledge of Precambrian seas, the supercontinent of Pangaea, or the Age of Dinosaurs. We are born into a world scarcely older than ourselves and scarcely larger than ourselves. And we are at its center.