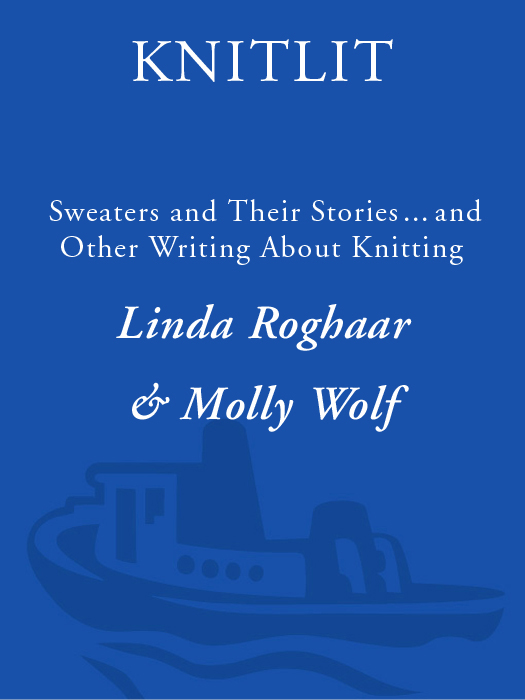

Copyright 2002 by Linda Roghaar and Molly Wolf

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Twenty Years and Still Growing reprinted by permission from Interweave Knits, Fall 2001. The Spinner reprinted from Hiding in Plain Sight: Sabbath Blessings, by permission of The Liturgical Press.

Published by Three Rivers Press, New York, New York. Member of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc.

www.randomhouse.com

THREE RIVERS PRESS and the tugboat design are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

KnitLit : sweaters and their stories and other writing about knitting / Linda Roghaar and Molly Wolf, editors.

1. Knitting. 2. KnittingMiscellanea. 3. Knitters (Persons)

Miscellanea. 4. Sweaters. I. Roghaar, Linda. II. Wolf, Molly.

TT825 .K639 2002

746.432dc21 2002005962

eISBN: 978-0-307-53583-2

v3.1

Contents

Foreword

Melanie Falick

Aside from a soft click-clack from the needles, knitting is mostly a silent medium. Though knitters can work and converse, there is rarely a need for words spoken aloud. Knitters use their fingers, their needles, and their yarn to create stitches that hold within them their thoughts and wishes. A pregnant woman knits for her soon-to-be-born baby. With her stitches she says, I want to keep you safe, I want to keep you warm, I love you. A mother knits a sweater for her grown child who lives far away. Into the stitches, she knits the same message, with maybe a Please call me added on. A wife sits in a hospital waiting for her husband to come through surgery and knits to calm herself, to give herself something to do with her hands while she begs invisible powers to heal her beloved.

To people who have never knitted or never received a handknit from someone significant to them, this may seem strange. To knitters, recipients of handknits, and the writers who contributed the essays in KnitLit, I am sure this concept of silent, intimate communication through knitting makes perfect sense.

In Peace Fleece, Peter Hagerty writes about how during the throes of the Cold War he came up with the idea of combining wool from Russia with wool from the United States to create a yarn that would say, At our core, we are more the same than we are different. Peace. In A Twist in the Yarn, Zo Blacksin recalls her grandmother telling her how her mother would whisper prayers into her wool. In The Baby Blanket, Jean Stone writes about knitting a blanket for the baby she gave up for adoption; within the stitches were her prayers for his good life. In knitting, all of these people have found a voice, a way of expressing both who they are and what they feel. They have found a way of touching their coretheir souland letting others around them touch it as well.

In this book, knittersand people whose lives have been touched by knittingtell their stories. Some are happy; some are sad. They take place in homes, on mountains, on the road, and amidst travel to faraway lands. Though they are all different, in one way or another, they all deliver a similar message: Knitting may not, on the surface, seem relevant to the engines that run the world, but at its essence, it is actually quite vital. For knitting, which can express so many emotions, most often expresses love. And when all else is lost, love is what most often stays with us.

Melanie Falick is editor-in-chief of Interweave Knits magazine, coauthor of Knitting for Baby (Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 2002), and author of Kids Knitting (Artisan, 1998) and Knitting in America (Artisan, 1995).

Preface:

A Conversation

Molly says:

Since it was Lindas idea in the first place, she should go first.

Linda says:

I want to share with you a memory that I havent thought of for years, until I started to write this introduction. When I was in elementary school, every fall my mother made the most wonderful knee socks for me. They had cables, ribs, and patterns, and they matched my outfits perfectly. She also made special garters to hold them up. For all those years, I wore skirts every day, but my feet and legs were never cold.

I learned to knit as a child. But I didnt discover the connection between knitting and love until I began to knit sweaters for my high school boyfriend. I carefully threaded my blond hair into each oversized, misshapen sweater, and he wore themwore them faithfully, and in public. My mother would look at him wearing one of those monstrosities, and she would shake her head and say, That boy really loves you! When he and I parted, I stopped knitting. I didnt pick up the needles again for thirty years.

At a camp reunion a few years ago, I reconnected with my childhood friends. By now they were (almost) all knitting, joyously obsessed with luscious yarns. I said, I used to know how to knit, and my friend Janet told me, Your hands remember. She was right. I went home from the reunion and straight to my local yarn shop. My hands did remember, and soon I too was hooked. (Is obsessed too strong a word?)

I found that knitting books were lovely, useful, and full of patterns and history. But one of the things I loved most about knitting was the stories knitters share with each other as they work, and I found no books of those stories. So much of my own work these days revolves around community and the strength and support I receive from it. I realized that the knitting community, which overlaps so many others, is about connection and love. I wanted a book about that connection. And thats how the idea for KnitLit came to be.

Now, I have done much of the end work of publishingthrough my career in book sales and marketing and as a literary agent. But I had never in my life actually made a book. I knew I needed help. I called my friend and colleague Molly Wolf, who, as an author, editor, and indexer, has done all the other parts of bookmaking from soup to nuts. The two of us split the responsibility for the project: I solicited contributions, connected with our publisher, Three Rivers Press, and organized the promotion and publicity. Molly, who has a gift for organizing literary shoeboxes, sorted through the contributions, picked out those that fit with our theme of community and story-telling, and gave each piece a light editorial going-over.

Molly says:

As I went through the stack of contributions that Linda had put together, I found something curious and wonderful. All the stories had, of course, something to do with knitting, or with wool, or with sheep, or with dyeingsome sort of connection with those luscious yarns Lindas friends so loved and with the knitted stuff that people had made of them. But the best stories went much further than that. They were about wonder and suffering, love and high mountain paths, childhood and dancing with a dying grandmother. They were by turns poignant, funny, insightful, wise, strong-minded, deep, ebullient, and occasionally joyfully silly. Best of all, a fair number of them (and some of the best of them) came from men, not women. That was an unexpected pleasure.