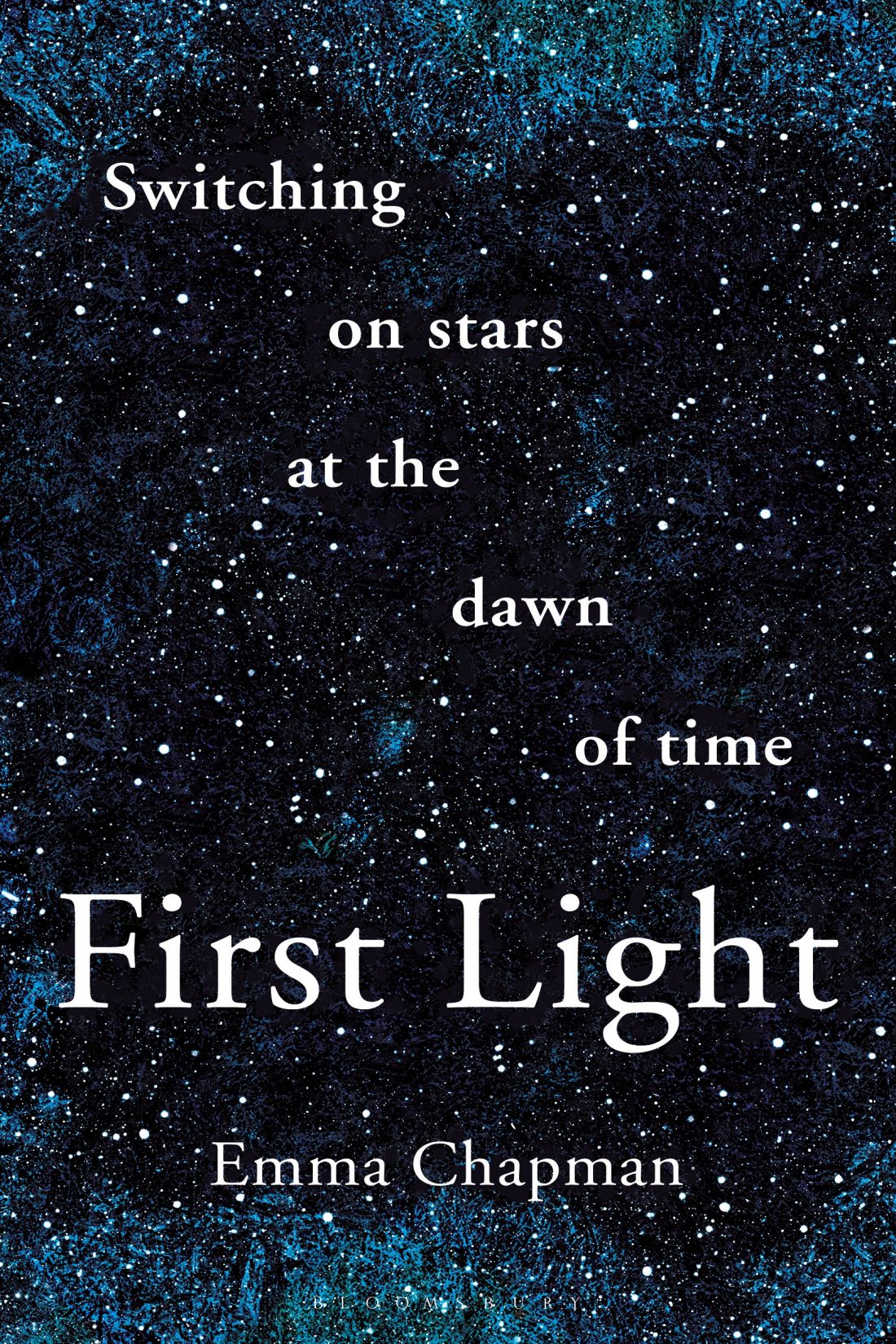

Emma Chapman - First Light

Here you can read online Emma Chapman - First Light full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Science fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:First Light

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

First Light: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "First Light" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

First Light — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "First Light" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Also available in the Bloomsbury Sigma series:

Sex on Earth by Jules Howard

Spirals in Time by Helen Scales

A Is for Arsenic by Kathryn Harkup

Herding Hemingways Cats by Kat Arney

Death on Earth by Jules Howard

The Tyrannosaur Chronicles by David Hone

Soccermatics by David Sumpter

Big Data by Timandra Harkness

Goldilocks and the Water Bears by Louisa Preston

Science and the City by Laurie Winkless

Bring Back the King by Helen Pilcher

Built on Bones by Brenna Hassett

The Planet Factory by Elizabeth Tasker

Wonders Beyond Numbers by Johnny Ball

I, Mammal by Liam Drew

Making the Monster by Kathryn Harkup

Catching Stardust by Natalie Starkey

Seeds of Science by Mark Lynas

Eye of the Shoal by Helen Scales

Nodding Off by Alice Gregory

The Science of Sin by Jack Lewis

The Edge of Memory by Patrick Nunn

Turned On by Kate Devlin

Borrowed Time by Sue Armstrong

We Need to Talk About Love by Laura Mucha

The Vinyl Frontier by Jonathan Scott

Clearing the Air by Tim Smedley

Superheavy by Kit Chapman

Genuine Fakes by Lydia Pyne

Grilled by Leah Garcs

The Contact Paradox by Keith Cooper

Life Changing by Helen Pilcher

Friendship by Lydia Denworth

Death by Shakespeare by Kathryn Harkup

Sway by Pragya Agarwal

Bad News by Rob Brotherton

Unfit for Purpose by Adam Hart

Mirror Thinking by Fiona Murden

Kindred by Rebecca Wragg Sykes

To Lyra, Cassie and Olive.

Never stop asking questions

Contents

Writing this book was hard, I wont lie. Shortly after I signed the contract I found out I was pregnant, so I ended up having not only to birth a baby but a book too ... and Im not entirely sure which was harder. The only reason it happened at all was because of the help and love from the below.

This work would not have been possible if not for generous support from the Royal Society in the form of the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship, providing a flexibility to academic research that is an example to be followed. To my Bloomsbury editors, Jim Martin and Anna MacDiarmid, without whom there would be no book, thank you for taking a chance. Thank you to Lon Koopmans, Abraham Loeb and Howard Bond for being so generous with their time and answering my many questions. Thank you to Mattis Magg, Paul Clark, Joshua Simon, Katie Paterson, Manu Palomeque, Richard Porcas, NASA, ESO, ESA, Michael Goh, ICRAR and the Illustris Collaboration for their kind permission to reproduce their figures, photographs and artwork. I am forever indebted to Ryan Stimpson, Phil Parker, Brett Handley, Paul Woods and Steven Chapman for their invaluable comments and suggestions on the manuscript, thank you so much for taking the time. Jonathan Pritchard, you gave me the space to figure out what kind of a scientist to be, and I couldnt have stayed in astronomy or written this book without your support, thank you.

Steve, you have taken on far more than your fair share of cooking, cleaning and cheerleading, and without a grumble. I love you and love life because of you. Thank you. Lyra, Cassie and Olive, my three little stars. Lyra, your curiosity is inspiring and reminds me why science is so wonderful when I get too focused in on the complexities. Cassie, your passion for life reminds me to take a break and have fun. Olive, your chuckles make me explode with joy. Mum and Dad, thank you for bringing me up to see the wonder in everything and above all keep asking questions. Maxine, Sarah, Phil and Bill, thank you so much for all the babysitting, sleepovers and family dinners that you provided for the kids while I worked. Rachael, Christine, Sue, thank you for being wonderful friends and being so understanding when I complained about the intricacies of book writing, always.

And of course thank you to anyone who has bought the book and even read to the end of this part. I hope it means you enjoyed it as much as I enjoyed writing it. Because, as hard as it was, it was the most wonderful experience.

Teach me your mood, O patient stars!

Who climb each night the ancient sky,

Leaving on space no shade, no scars,

No trace of age, no fear to die.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

In an age where we have particle colliders and space telescopes, its hard to imagine a time when we could solve the biggest questions of the cosmos by just looking up. Look up at the night sky, and what do you see? You might be lucky to live in an area of low light pollution, so perhaps you can see the Milky Way splashed across the sky. Or perhaps there is a full Moon. Overall, though, the key characteristic of the night sky is that it is dark. Why? The littlest of words with the biggest of consequences.

For centuries, natural philosophers, physicists, astronomers and even poets wondered why the sky is dark. Their belief was that the Universe was infinitely old and infinitely large, as they had no evidence to the contrary. Olbers paradox (named after the German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers) states that if the Universe is infinitely old and unmoving then every direction you look in should land on a star. The problem captured the imagination of many and even Edgar Allan Poe weighed in, in his 1848 prose poem Eureka: Were the succession of stars endless, then the background of the sky would present us a uniform luminosity, like that displayed by the Galaxy since there could be absolutely no point, in all that background, at which would not exist a star.

The sky should be as bright as the Sun, everywhere. Well, thats not right, because if that were the case wed have no need for street lighting. And so we wondered, for generations, what made the sky dark. To break a paradox, you break the assumptions, and in this case both assumptions of infinite age and lack of movement are wrong. Our Universe started with a Big Bang, beginning the expansion of space-time. In one fell swoop, the Big Bang requires the Universe to begin (i.e. not be of infinitely old age), and expand (i.e. move). We can solve the paradox because, even though it has been 14 billion years since the Big Bang, insufficient stars have been born for every line of sight to land on a star. Even in the deepest images from the Hubble Space Telescope we see that the galaxies account for only a small fraction of the picture, and each galaxy hosts billions of stars. Breaking the assumption of an infinitely old Universe has profound consequences. The Universe began. There were not just stars, but first stars, and second and third stars for that matter. What we experience now is only one stage of a much bigger cosmological lifetime (Figure 1). Its a lifetime that we can be pretty smug about understanding. We have observations of young and old stars, galaxies that are ancient and galaxies that are newly formed. We live in a time with unprecedented access to the Universe and its history, and our ability to fill in those gaps in knowledge has increased at a lightning-fast pace. Astronomy has broadened from a necessity in ancient civilisations, through a curious hobby for the rich, to an existential science broadcast to the masses. It has become so much a daily part of our lives that, while once we celebrated the discovery of new stars and new galaxies, now we barely lift an eyebrow if we discover a new planet. We understand our Universes lifetime, even right back to the Universes birth story: the Big Bang. We have lots of data but it isnt enough. Despite the exponential increase in technology and progress, there is a period in our Universe that, until recently, we had no observations of at all. From 380,000 years after the Big Bang to about 1 billion years after it, the Universe has remained in the Dark Ages. The first stars were born less than 200 million years after the Big Bang. Formerly, the Universe had been dark and empty until a simple star roared to life. A chain of internal nuclear reactions sparked into operation, producing light and heat into the barren surrounding space. Another star lit up, then another, until they speckled the sky with the dawn of first light. It was too early for planets, so there was no one around to witness that initial burst of star formation or mourn their almost immediate deaths. As the second population of stars established itself, that first generation was quickly forgotten, yet it was their intervention above all that prepared the Universe for the immense variety of structure and life that we see today. The absence of observations from the era of the first stars is alarming your local astrophysicist for two reasons.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «First Light»

Look at similar books to First Light. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book First Light and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.